Paying for Open Access does not increase your paper’s impact, but self-archiving in a repository does

An article by Nick Wehner, Director of Open Initiatives at OCTO | Open Communications for The Ocean – originally published at marxivinfo.org.

Numerous studies have found that Open Access papers are cited significantly more than the global average. Across all scientific disciplines, the average citation increase is 30%. If that’s not a compelling enough reason to make your research Open Access, I don’t know what is!

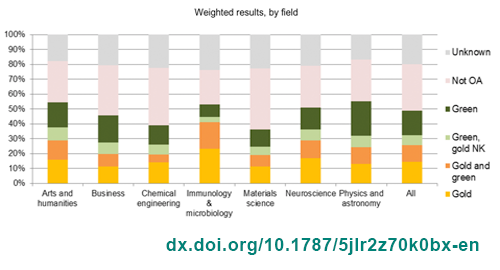

According to a [2016] report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the citation impact driven by publishing your research Open Access* is caused by papers that are Green Open Access — where the author “self-archives” their work in a central repository, commonly an institutional archive or a public, discipline-specific repository like MarXiv [or regional specific like AfricArxiv]. The effect is largely not caused by papers that are Gold Open Access, where the paper is available for free directly from the publisher. Why might this be the case? Let’s start by getting our terminology straight, first.

*As opposed to being behind a journal pay-wall, where it typically costs $30-60 to read a single PDF for a limited time, if you don’t have an institutional subscription to the journal.

The Colors of Open Access

It is not uncommon for authors to pay upwards of $1,000 to publishers of hybrid journals (where most papers are pay-walled, but some are Open Access) to make their work Gold Open Access. Yet, having your paper available for free directly from the publisher does not lead to much of an increase in citations, according to the OECD’s research and other reports.

Authors are increasingly making their papers freely-available without paying any publishing fees by archiving their work in institutional or public, nonprofit repositories. This is known as self-archiving or Green Open Access. Nearly all publishers support Green Open Access.

This figure from the OECD report shows a growing percentage of the research corpus is now available via Green Open Access.

Since publishers typically require authors to transfer the copyright on their own work that they had by writing it over to the publisher, authors lack the legal rights to do whatever they want with their published papers. It’s illegal for an author to share the PDF of a typical research paper they wrote on a public mailing list, for example. Just like it’s illegal to put that same PDF on a public website. Nor can authors share pay-walled papers with anyone who isn’t a “known student or colleague” (yes, it is illegal to share the paper with your mom or partner, provided they’re not a student or your colleague). The gist is that once you don’t have copyright of your own work anymore, you have to follow the rules of your publisher/copyright holder. So what do these rules typically look like?

Preprint, Postprint, and the Version of Record

According to academic publishers, there are three versions of every published paper:

- The preprint, also known as the original manuscript or submitted manuscript: this version does not have any revisions from the journal;

- The postprint, also known as the accepted manuscript: this version has all the edits from peer-review and the journal’s editors;

- And finally, the version of record, also known as the final version or the publisher’s PDF: this version has all the peer-reviewed edits just like the postprint, but it also has the journal’s formatting/typesetting.

With Green Open Access, publishers typically place restrictions on which versions an author can share, where they can share it, and when it can be made public.

Generally speaking, most publishers allow the preprint to be shared anywhere at anytime. It’s most beneficial for authors to submit their preprints to public repositories before submission to a journal so that it can be improved from community peer-review.

Postprints, on the other hand, are typically placed under an arbitrary embargo of anywhere from 6-months to 2-years. This means the version of your paper with peer-reviewed changes from the journal can only be shared publicly (for the most part) after the publisher has had ample time to charge for access when the research is fresh and new. They don’t get profit margins of 72%, higher than that of Google and Apple combined, without embargoes or charging for both publication and readership! Postprints are often only allowed to be shared in discipline-specific non-profit repositories, or institutional repositories like that of your university.

Note that this means it’s usually illegal to share your postprint on for-profit websites like ResearchGate or Academia.edu. ResearchGate is now facing a lawsuit from the major publishers and the American Chemical Society for massive copyright infringement. The publishers are seeking $150,000 in damages for each infringing paper. There are likely hundreds of millions of copyrighted papers on the platform. Thankfully, even though the publishers could be suing individual authors for illegally sharing their works on ResearchGate, they are not, as of yet. Consider yourselves lucky!

The version of record usually cannot be publicly shared anywhere, ever. Unless, that is, you pay to make your paper Gold Open Access. According to the OECD’s and other’s research, you barely get any benefits from paying to make your paper Open Access. But you do get a sizable impact boost from simply self-archiving your preprint or postprint. Sounds strange, right? Well, not once you know about the publication ecosystem and how the internet works.

It’s All About Discoverability

The above figure from the OECD report shows a growing percentage of papers may be found online beyond just the publisher’s website.

Academic publishers don’t like their papers to be found on the internet

Strangely, for-profit publishers do a lot of work to make sure their papers are not easily discoverable. Elsevier, for example, often includes metadata on the webpages for their published papers that tell Google, Bing, and other search engines to not index the content. If Google can’t read the webpage for your paper on Elsevier’s website, than your paper isn’t going to show up in any kind of internet search result. We see this happen all the time: our sister-project, OpenChannels, houses a literature library for all kinds of ocean-conservation research. It’s not uncommon for the OpenChannels Literature Library page to be the only search result for an academic paper on the internet.

Subscription databases are often the only way to find pay-walled papers

If you can’t find papers on Google or Microsoft Academic, where can you find them? In subscription databases like Web of Science and Scopus. Why might that be? Probably because Elsevier owns Scopus. You have to admit, it’s a rather ingenious strategy to ensure that universities need to pay for publication, readership, and discoverability of papers. It’s the perfect trifecta of income!

Metadata helps papers find a reader

Not only do the for-profit publishers often restrict their papers from being publicly indexed, they often do not provide metadata on their works. Other times, access to the metadata requires costly subscriptions, likely to make sure there won’t be a competitor to their proprietary databases. Taylor and Francis, for example, does not include any metadata about the papers on their website. Simple metatags on webpages like <meta name=”citation_journal_title” content=”A Scholarly Journal” /> allow databases like Google Scholar and Microsoft Academic to easily tell what they’re looking at. There are a number of open standards for ensuring research papers can be found online. This problem was solved decades ago, but the for-profit publishers of the world sure don’t act on it.

The public’s only option: repositories

It doesn’t matter if your paper is Gold Open Access if it’s only hosted by the publisher, and the publisher does everything it can to ensure you need an academic database subscription to find it. Gold Open Access papers simply aren’t discoverable by the people who would benefit from them.

So where does the public go? They use Google like everyone else. And what can Google index? Public, non-profit repositories that believe in the mission of Open Science. Repositories that ensure their papers are indexed by any and all search engines. Repositories that provide accurate and complete metadata. Repositories that, you guessed it, contain Green Open Access papers. It’s no surprise then why Green Open Access publications make the most societal impact.

TL;DR

You can pay to make your papers Gold Open Access, but if you do, ensure you self-archive it alongside Green Open Access papers in a subject-specific non-profit repository like MarXiv or any of our friendly repository brethren because we all want to actually read your research.

Questions? Feedback? We’d love to hear from you! Email MarXiv Project Director, Nick Wehner, at nick@octogroup.org, or tweet us @MarXivPapers, or join our Slack channel.