Bridging Academic landscapes.

At Access 2 Perspectives, we provide novel insights into the communication and management of Research. Our goal is to equip researchers with the skills and enthusiasm they need to pursue a successful and joyful career.

This podcast brings to you insights and conversations around the topics of Scholarly Reading, Writing and Publishing, Career Development inside and outside Academia, Research Project Management, Research Integrity, and Open Science.

Learn more about our work at https://access2perspectives.org

Christian stares at goats to better understand how they perceive their physical and social environment. His main research interests focus on animal cognition (in particular farm animals), applied ethology, and animal welfare. He is engaged in activities to increase the accessibility and dissemination of research via Open Science and SciComm.

In our conversation, Christian tells us why he chose goats to work with for his research, what Open Science means to him and how Open Science practices facilitate and influence his research progress. He explains to us the concept of 3R (Replace, Reduce, Refine) and how it can apply to experiments with goats as well as any other animal research.

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-4582-4057

Website: christiannawroth.wordpress.com

Twitter: @goatsthatstare

Instagram: goatsthatstare

Linkedin: /christian-nawroth-a1186a99/

More details at https://access2perspectives.pubpub.org/pub/a-conversation-with-christian-nawroth/

Host: Dr Jo Havemann, ORCID iD 0000-0002-6157-1494

Editing: Ebuka Ezeike

Music: Alex Lustig, produced by Kitty Kat

License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

At Access 2 Perspectives, we provide novel insights into the communication and management of Research. Our goal is to equip researchers with the skills and enthusiasm they need to pursue a successful and joyful career.

| Website: access2perspectives.org

Christian stares at goats to better understand how they perceive their physical and social environment. His main research interests focus on animal cognition (in particular farm animals), applied ethology, and animal welfare. He is engaged in activities to increase the accessibility and dissemination of research via Open Science and SciComm.

In our conversation, Christian tells us why he chose goats to work with for his research, what Open Science means to him and how Open Science practices facilitate and influence his research progress. He explains to us the concept of 3R (Replace, Reduce, Refine) and how it can apply to experiments with goats as well as any other animal research.

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-4582-4057

Website: christiannawroth.wordpress.com

Twitter: @goatsthatstare

Instagram: goatsthatstare

Linkedin: /christian-nawroth-a1186a99/

What is your favorite animal? Goats!

Name your (current) favorite song and interpret/group. Janosch

What is your favorite dish/meal? Currently, mushroom risotto

References

Rafael Muñoz-Tamayo, Birte L. Nielsen, Mohammed Gagaoua, Florence Gondret, E. Tobias Krause, Diego P. Morgavi, I. Anna S. Olsson, Matti Pastell, Masoomeh Taghipoor, Luis Tedeschi, Isabelle Veissier, & Christian Nawroth. (2022). Seven steps to enhance open science practices in animal science (Version 1). Zenodo. doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5891771

Nawroth, C., & Krause, E. T. (2021, October 21). A short primer on the academic, societal, and animal welfare benefits of Open Science for animal science. doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/dnfvs

>> published at frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2022.810989/abstract

Wikipedia contributors. (March 2022. Three Rs (animal research). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Three_Rs_(animal_research)&oldid=1079561715

Transcript

Jo: Welcome back to our Conversations podcast here I’m today with Christian Nawroth, who is working on – or should I rather say with – goats? Welcome, Christian.

Christian: Hi, Jo. Thanks for inviting me to a podcast.

Jo: Most welcome. So you and I, we got to know each other from Open Science Community, which is called Open Science Mooc, which still exists today and was inaugurated a couple of years ago. And that’s how we met. Was it two years ago?

Now we’re discussing Open Science and how it can be applied in ethology with your work environment as well. And we were conceptualizing a paper or some article on introducing open Science principles to the ethology community. And then for several reasons, probably as life sometimes gets in between, we lost touch.

But in the meantime, you kept working on this idea, which was originally also yours, to work with your colleagues on articles on Open Science and goats. But before we get to start about that in particular, would you please share with us, like, what your specific research focus is with goats? What your ambitions are like, what your working environment is, what Institute you work at? And so we get to know you a little bit better.

Christian:

Hi. My name is Christian. I’m currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Research Institute for Farm Animal Biology located in Domastore, which is close to Rostock at the Baltic Sea.

I have been previously working at Primary University as a research fellow, and I did my PhD at the University of Halle. And before that, I did my diploma at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology on great apes. So right now, I’m working with farm animals. In particular, I’m working with goats. And my main aim basically in this respect is to better understand how farm animals perceive the environment, how they interact with the environment. And this does not only include the physical environment. That means how can they physically comprehend their husbandry context, but also, for example, how they interact with humans and what knowledge they have about humans and how humans behave.

Jo: Well, that’s really interesting, being a dog owner on my own and knowing that dogs have been domesticated, like, I don’t know, hundreds of thousands of years ago by now, I think at least one. Anyway, quite a long time. And then farm animals like cattle and goats and chickens have been around humans also for a long time.

So that’s really a research area I haven’t even thought of. And yet now that you mention it, it’s like it’s super interesting to dig into. Like, how do these animal species who work so closely with us and also have bread into what they are today to serve us with nutrition and meet our direct products, how they perceive us. That’s super interesting. Why did you choose goats in particular from the range of farm animals available?

Christian: That’s a rather long story. I tried to have it quite short for the podcast. So for my diploma theaters, I was working actually with great apes. So I investigated decision making great apes, risk taking in primates, which I found extremely interesting. So I was confronted with this whole cognitive approach and how to conduct cognitive experiments with animals. And I wanted to pursue this during my PhD thesis. So I was looking for places where I could run experiments, cognitive behavioral experiments with animals in general. And for some reason I ended up at the University of Halla because they’re at the Department for Animal Science, they offered a PhD position, I applied for that. And my idea was that the things that I’ve learned, what has been done with primates and what you can do with primates in terms of conducting cognitive experiments. I wanted to apply this to farm animals because doing the literature review for the primate studies, I soon realized that there is not a lot of literature in this regard on farm animals. You already mentioned dogs. There is a plethora of research on dog ignition for various reasons. There are many labs in the world that work on this topic, but surprisingly there was very little and still is very little research on farm animals. So I was happy, but also surprised that I got this position. I proposed to run first experiments on cognitive experiments with farm animals and I actually choose pigs to work with. Again, long story short, facilities were not adapted to run studies with pigs. So this took a lot of time to have a test arena to have a test set up for the pigs. And in the meantime I was visiting some small farmers’ sanctuaries near Live Sick or Dresden. And there I was confronted with goats or with a lot of goats there as well. And I thought, well, let’s try goats. Maybe it’s easier to work with goats and with pigs if you have worked with pigs or if you’re familiar with pigs. It can be quite tricky, for example, to let them focus on visual cues. So they are really all factorial and acoustic motivated. So it’s really hard if you, for example, want to show them something in a test environment, for example, where the food is hidden, it’s really hard to get their attention if you only focus on visual cues. So I thought maybe goats might work better in this regard. And indeed they did. So it was relatively easy to train the goats to indicate a choice. If you have, for example, two cups and they have to choose one of these cups and they really pay a lot of attention in the visual domain. So this made it really easy to work with them and in no time I became a big fan of goats. I think at least when I went to Queen Mary University, I worked at a sanctuary for goats or collected data at the sanctuary for goats.

From that point on, basically my main focus was on goat research and here in particular on how goats interact and communicate with humans. So that’s basically the long short story, how I went from primates to pigs to goats. A lot of luck and a lot of coincidence, I guess, but I never regretted it.

Jo: So pigs are also known to be super smart animals. Would you say the same about goats, which are commonly referred to as not as smart as other species? Whatever you compare it to, I don’t know if it’s even in my opinion, it’s not a fair measure really, but just because there’s a lot of what’s the word common misconceptions about various societies about animals that we live with. In my idea of what or in my anticipation and assumption, it’s that animals are perfectly adapted like humans to their specific work environment and needs that they have due to their anatomical setup. But from your experience in working with goats and also having worked with great apes and pigs for some time or considered looking into it in more depth, is there anything that’s comparable, that you can apply a measure of intelligence or anything like that to the animals?

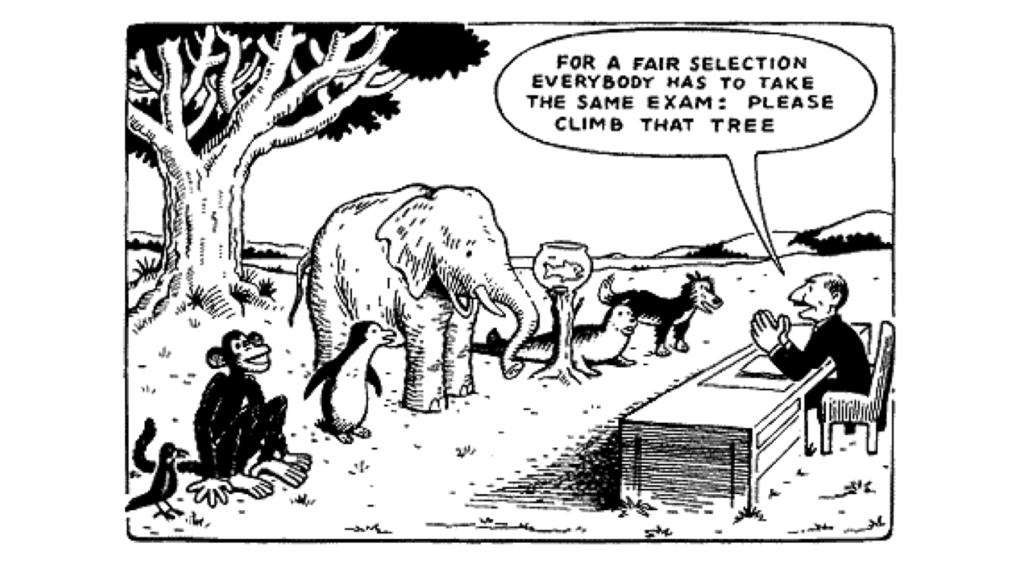

Christian: I think you’ve got it already quite good in a way that it wouldn’t be a fair comparison in most regards. There’s the famous cartoon where a person asked a fish to climb and wants to measure the fish’s ability to climb that says, well, you can’t climb, you’re not smart enough to climb in many cases, just the case that we as humans look with our abilities, with our environment, that we grew up on the abilities of animals and then judge them according to whether they are similar to us or not. So we might think that pigs are indeed extremely fast learners. So we might think that pigs appear smarter to us because we can learn very quickly to adapt to new environments. But this is exactly what they do in the wild. They are omnivores, they’re opportunistic, so they try to exploit as many food sources as possible and they have to learn really quickly what they can eat, what they cannot eat, which food they have to disregard. Where are you? They have to remember food patches throughout the area, and the food patches are often under the ground as well. So there’s a reason why they are such good learners. Goats are good learners as well, but we never did a fair comparison either. But in my personal opinion, they learned a little bit less fast than the pigs do. But again, this is just because of their natural habitat. So there is no such strong need to be an extremely fast learner, because on the other side, having the cognitive capacity. So having the mental capacities to memorize a lot and to learn a lot also means that you have to put energy in this. So it’s always a tradeoff between the mental capacities that animals have and to which degree they are expressed in them. So, yeah, I wouldn’t say it’s a fair comparison not just to compare primates with pigs, but also just to compare pigs with goats because they differ extremely in terms of their ecology or ecological background and natural foraging ecology.

Jo: Yeah, thanks for that. And also maybe to draw just one more comparison on two animal species that seem very similar such as sheep and goats. I think I found this in your reference list or one or the other of your own research articles is that when you compare the two, they differ drastically in the way they conceive information and process information, even though they look almost the same. And what I learned from the article is that if you look back into what natural habitat they have, it’s totally different. Like sheep are presumably stupid from our observations as humans and what we deem intelligent, whereas those goats seem more intelligent and clever and agile or whatever solution oriented. But then, as you say, if you consider the natural habitat and the evolutionary aspects and the physical conditions, like despite the mere look and phenotype of the outer appearance, then it’s clear that, of course, they are different species and they also have different skills and assets which are not comparable one to the other. Do you want to extrapolate on that a little bit?

Christian: Yeah, I can just try to give a quick recap on this. So indeed, we had two studies where we wanted to compare gold behavior and cheap behavior. And I think the main message behind this is that goats appear to be in certain contexts more flexible in terms of their learning, which we try to explain in a way that goats are in their feeding ecology. They are more picky eaters, basically, than sheep. So for sheep, you would have a lawn or Meadow, and that’s fine for them. They can rely on grass all the time, while goats rely very often also on fresh leaves, dams and other more energetic plant resources or plant sources. And for those you have to basically you have to be a bit more flexible. You have to remember where these were located, where you have to go, and you have to make different decisions than, for example, the food is just dispersed below your feet. So this is why we try to explain or how we try to explain this difference that we found between the two species. But this is just one explanation. Also, they look quite similar. There are many other differences, like the social structure or the cohesion in the social group. So sheep tend to stick more together, so they lump together when they are running away, for example. Well, this is more our impression if goats run away, they disperse. It’s not that they clinch together or most of the time clinch together, they try to go different routes sometimes. So there are other factors as well that might be at play on this, but one of the main things because you mentioned that coming back to the style that goats or sheep might not be perceived as very clever in the public or by society, I think one of these reasons is that they are prey animals and when you walk nearby them they see all the things moving, they stand still and then they just look at you and I think this gives easily the impression that they do not know what to do right now. They don’t make a decision, they don’t make an action in this regard, so they’re just waiting for you to do something. This might give the impression that they are not very proactive in their behavior and in turn might not be perceived as very intelligent, at least to what we would perceive as intelligent as humans.

But I think the thing that we completely miss is what is going on in their brain basically when they are standing still and observing what’s going on. So what are they calculating, what are they processing, what are they anticipating comes next? So this is something that we do not see and that we have to infer from, for example behavioral experiments.

Jo: Suddenly I had a funny thought as you mentioned this and the comparison with the goalkeeper. So while they’re processing and anticipating what the next move of the predator might be, they’re probably outsmarting goalkeepers by a huge scale and being able to read in the enemies or the other leaks team what’s going to happen next after doing such a thorough study or not. So coming towards the topic of open science, what does open science mean to you and in your particular research field?

Christian: I will try to explain this in a more chronological order. I think for me open science at the very beginning meant that it helps us as researchers, in particular in our field when we do experiments or behavioral experiments with animals and basic research that we can better disseminate this research, with this better dissemination, we can better explain this research so it’s open, it’s visible to everyone, everybody can read about this and it’s a better justification why we are doing this research and we as researchers have the opportunity basically to explain ourselves better, why this research is needed and even if it’s basic research, how it can be, for example applied somewhere in the future. So we can justify why we have to do this research. And I think this is something that is crucially important in particular when we mainly rely on basically taxpayer money when we are conducting this research. So this is basically the key argument that I came from before. I actually really thought about open science as a whole. It was mainly the point of dissemination. And from that point on, when I walked more into the whole topic, I found more and more arguments that I thought were more and more relevant for our research as well. Yeah. Like thinking about your research plan before you start experiments, having clear hypotheses justifying a sample size, having probably your test protocol peer reviewed before you start, before you actually use or exclamation marks to use your animals in the experiment. So having quality control or more quality control before you start the experiment, I think are crucial parts that need to be implemented further in our field in particular.

Jo: Thank you. So talking about sample sizes, how many codes do you currently work with to have some cody aspect on this topic?

Christian: Again, this usually depends on the accessibility. So we have a facility where we house the goats here at the Institute, and when we conduct studies, we usually rely on, let’s say, ten to 40 animals.

This highly depends on the test schedule and basically how many researchers are involved because we can only test so many goats in one day or in one week. And right now in a new test paradigm that we are trying to pilot, we just run with six goats where we want to see how they behave in the new paradigm and how this might work. But usually we are somewhere between ten or 40 individuals.

Jo: Okay. How are open science practices and what is the open science community at large trying to accumulate as knowledge and best practices? How’s this informing your current and ongoing research? Do you see that you can draw from this and apply? I’m sure there’s plenty. But if you could just give one or two examples of how open science practices inform and possibly also improve your research, Besides what you already mentioned in having a more thorough project planning to start with, and then what else can I inform your research?

Christian: The one thing that bugs me right now the most is that I’m talking in these articles that you mentioned as well. I’m talking about registered reports or pre registrations, and I’m going to implement this by doing the next experiments. But this can be particularly hard for exploratory research for pilot studies where you do not know what to do next. Preregistrations, I think, are one crucial element that needs to be adopted in the field of applied ethology. But what I thought informed me as well the most was just learning about why pre registrations are necessary. So this led one thing to another, like as I mentioned, thinking about justifications for sample sizes, thinking about clear hypotheses at the very start, something that is clear for every researcher. But just digging into the literature basically, and reading why it’s really important to stick to these hypotheses and why it’s really important to stick to your research plan as a justification or as a measure for more robust research at the end.

For people who work with animals, in particular with some animals or domestic animals, they know that often if you conduct research, these plants can diverge over the course of time because animals don’t behave as you expect or you have to adjust the set up a little bit. So I understand that it’s difficult to stick to your research plan, but the more I read about pre registration and why it’s important, the more I try to implement this not just simply as a pre registration, but also am I thinking about novel test designs, novel test protocols, and how they have to be set up. So yeah, this kind of shaped a lot of my thinking about how research is supposed to be conducted versus how research is sometimes also conducted in a more exploratory way. But yeah, people like narratives. So it’s always interesting or more interesting to have a fitting narrative to exploratory research. But it took a while to get some inner knowledge on this.

Jo: My experience is also that some of the skeptics always argue with academic freedom. Like you said, explorative research. Like I cannot come with a plan because we’re here to do research and to learn on the goal. I think both approaches are valid and maybe both can meet in between. And to my understanding, pre registrations and registered reports are also not enshrined in stone. That’s what I usually convey. My courses also are meant to change along the way. Of course, if you make a discovery, if you find that your hypothesis is difficult to come by because there’s not enough animals to work with or whatever other constraints you experience despite your expectations and planning. And of course there should be room for flexibility and agile approaches to reassess the situation and to make best possible use of the resources, including the funding and also the animals that we work with, as well as human capacity, equipment, and other things. Yeah, it’s interesting to hear from you how this is actually informed and allowed you to also learn how methodology and also the use of how many animals do we actually need for this question to find answers to over the course of the project? Thinking presumably only about pre registering the study, making a plan for it, which is often also required by funders in more or less data, but that also informs methodology and basically saves time and money at the end of the day or towards the end of the project. And my observation is especially crucial to my personal experience for timely, limited research projects like PhD studies or otherwise timed project activities.

Regarding the methodologies and also statistical analysis. Is there anything that the open science approach has helped you there as well,

Christian: But I found it very valuable for our own research approach or for working with animals where you have restricted resources in terms of time and the number of animals that you have. Thinking about your statistical analysis plan on your test design, whether you’re using between subject design or within subject design; what are the advantages of the one and the other, and which statistical approach you want to use when you want to analyze the data that you will collect? I think help me personally a lot to improve my own approach to the research that I’m doing in terms of that, I’m spending way more time trying to get all of this straight before I started to collect data or before I actually go into the bound and conduct the experiments because it helps me at the end, after I have the data collected, I already know what I want to do with this data. I do not just out of a sudden I’m confronted with that I missed some crucial parameter that I should have measured doing this just because I did not sort of really through and what I really want to get out of the whole thing. So this really helped me in my own approach. So this is, I think, something that is extremely valuable, not just for the sake of having a pre registration but just for the scientific work that we’re doing in general.

Jo: And this is totally fine. Also with the fair principles, I just want to explain that just briefly to make research data in particular case, it’s logical data like the behavioral aspect that the goat showed to you; findable, accessible, interoperable and also reusable. And that doesn’t mean just for the listeners out there, it doesn’t mean that it has to be open and made publicly available, often the opposite. But it’s important for the researcher to have a way to document and to also anticipate results that you collect, often as a byproduct, and still also keep track of these byproducts because they might prove themselves useful in the future for future analysis and therefore can also be reusable for the very same researcher and research team as soon as we progressed in our research project. You’ve published, as mentioned in our introduction, two articles, particularly on the intersection of open science and animal research. One is from the end of October last year, a short primer on the academic, societal, and animal welfare benefits of open science for animal science, you published together with a colleague. And then this year you shared a preprint on the seven steps to enhance open science practices in animal science. Could you please in a nutshell, what are the take home messages of both articles where the later one says on title there are seven guidance steps. And also on the second answer approach, what was the feedback received so far from the animal science community or the ethology community?

Christian: The whole journey basically started, and which also let me myself think more about how these open science practices can impact on animal or applied Animal research was at a conference that I visited, I think in 2019, good old times where there were still in person conferences where I met with this colleague, Tobias Couuser from the Institute of Seller. And after my talk, which was about good behavior, we for whatever reason ever started chatting about open access publishing and how this is increasingly common in our field as well, and all the other or more or less common open science practices.

And we came up with the idea to draft something together or write something together on how this actually might affect our research and the welfare of the animals that we’re using for this research. So this is basically the backstory of the first paper. This took a really long time. There were other commitments, and we just passed this. And at some point we assumed writing on this. So the idea here is to show the connections between open science practices, in particular, open access publishing, pre printing, and pre registrations, and how they might have an effect on animal welfare of the animals that we’re working with and research. This doesn’t necessarily mean that it has an impact on the very animals that we use in the research that we’re doing. But in research in general, just an example, faster dissemination via pre printing or open access publishing can often lead to the idea, that notion that other researchers became aware of your research that might plan research to answer a similar question like you did, having a pre printed, they can already look at the protocol, they can see how this works for you and what are your results and can potentially adapt their own protocol to improve it and to not rerun it basically just to make the same errors that you did or to improve it in terms of adding something novel. So they’re not rerunning your experiment and basically trying to answer the same question. But there are also other interconnections that we think are worth to discuss, for example, or in particular, pre registrations, where you can get feedback not just about whether this is an adequate test design that you’re using, but also whether you were trying or whether there are improvements possible in your test design to further refine the environment, the test environment in order to not compromise welfare of the animals that you’re using in your test, but also whether there are already adequate non animal models that you could use to answer your research question. So these are the aspects that we’re dealing with within this first preprint. I’m currently working on the revision of this, so we hope to get this published or peer reviewed and published over the next week. And the second article kind of came along on the same journey. So writing on this topic led me to dig deeper into the whole literature. And at some point, Anna Olson, which is a colleague from the University of Porto, got in contact with me, and we kind of run in our field and plant pathology to workshops on open science because we realized that a lot of people know about the topic but do not know about the details and in particular, do not know about how to implement them. So let’s say people know what a preprint is, but they never pre printed. So we, for example, were interested, why have never pre printed? You know what a preprint is? Why don’t you do this? And we were surprised that many people were basically in this workshop saying, we don’t know why, we don’t know how to do this. Basically, we don’t know what to do exactly and what we have to take care of and what are the advantages and what are the disadvantages or potential disadvantages? So from these workshops, we came up with an idea, okay, there seems to be a lack of training on this. Why not do a short article about, hey, Open science is very valuable for the field, not just because we as researchers can benefit from it, but also as the animals that we’re working with. So we are proposing in the second article, seven easy steps for animal science researchers that they can implement in their research. We are aware that there are many other resources out there, but we aim to publish this in a Journal that is dedicated to animal science, and we hope to reach more people in our field and that they then might start or have an easier start implementing these practices as well, just to name a few. One thing is, of course, that people should start pre registering the work, but also that they might consider pre printing. Some of the other steps are, for example, for previous research that they have conducted, that they have published not under open access license, that they should be aware that there’s a screen open access route so they can deposit post print versions of their articles to repositories to make it accessible to everyone. And people can actually find the research and are not confronted with the payroll. This is something that many people are actually not really aware of and they are not aware of. And if they are aware of, they are not really aware, what are the legal boundaries of this and whether they can do this with the research or with this particular article or not. So we’re trying to give a lot of help and assistance and a lot of resources as well where people can read and make more informed decisions about this.

Jo: Thank you for that overview of what’s inside these articles and how they came about. We will, of course, list the articles also in the show Notes and a blog article that’s connected to this episode. And now, have you received any feedback since you published this online except for the feedback that you directly received in the workshops? Have people approached you and given comments on the recommendations that you have terminated.

Christian: I think we hear basically the same experience as many people do when they publish Preprints. That feedback is often very limited, so we got some positive feedback in terms of this is necessary. We need to inform people in the field about this in terms of feedback on how to improve this or how to make it more readable or better to comprehend for the reader. We haven’t got feedback such as this. But this would basically go hand in hand with a better implementation of pre printing, for example, in the publication process in general. So more people are aware of Preprints about the opportunity that they can comment on these preprints or just contact you and write you an email. So we hope that this will improve in the future as well. Yeah, we got very valuable feedback from the reviewers, which is great. So this helps us also to improve the manuscript.

Jo: Perfect. On any research article, you often have the email address of the corresponding author, which implies that people are waiting to receive readers’ comments and feedback. So for anyone out there reading research articles preprints and if you have questions or remarks to make, please get in touch with the authors. They are keen to hear from you, Christian, and your work here. Are you presented to inform and if there’s any questions and just ask, I think well, obviously highly relevant to animal research in particular. Maybe not as urgent in your research field of cognitive animal research, but in other areas more so. Other three are approaches, which stands for reduced replace refine. Have you found ways I think you already mentioned that in another context in an earlier question, or your responses thereof, but in particular, could you maybe extrapolate a little bit about 3 hours? The necessity why this is an emerging discussion to have in the animal research arena at large, and if at all, it applies to your research in particular, we can make use of any of those concepts and also private what you already said, how it refers back to open science practices like preregistration. I think we covered that there as well, but I just wanted to highlight the theorem.

Christian: Of course, the CRS are highly relevant for our own research as well. We are mostly conducting non invasive research. We most often only measure behavioral responses of the animals, but nonetheless this often means that we have to confront them with more or less stressful situations, for example, when we have to isolate them, or if we, for example, want to measure the stress response. Because we are interested in how stressful a certain event is and see whether treatment or intervention can reduce stress. We are relying on these principles and we try to implement them in our research as well. Which again comes back to thinking about your statistical design, having discussions with colleagues before we start data collection, trying to go within subject design to reduce the number of the animals’ ideas or considerations on how to refine the environment of the animals. So if you expose them to stress, for example, if you won’t need to for what experimental protocol, whatever. If you need to punish them because they did something wrong or made the wrong choice, find a punishment that is negative, perceived negative, but is not harmful in any way to the animal. So they still learn. But you do not decrease welfare in an unnecessary way. So there’s a lot of discussion about how we need to better implement this as behavior or people that work on animal behavior or platinum behavior. We do not really rely on the replacement in this regard because we are actually interested in the behavior of the whole animal. We cannot just replace the whole animal and try to study the behavior of the animal. So this is something that is more the focus of other areas of research, of animal research. But when it comes to refinement and to the reduction in the use of these animals, we strongly rely on this and open science. I think I mentioned this for the pre registrations, but also with a better dissemination. We are pre-printing and open access so that we can try to find synergistic effects between both of those. So implementing open science because it benefits us as researchers, but it can also at the same time benefit the animals that we are using for this research.

Jo: Yeah. So what I hear from you and also what I’ve preached myself, on courses, is that open Sciences is nothing new. It’s good scientific practice. And I usually introduce open science as tsp good scientific practice in the digital era that we now live in. So there are new concepts, there are new tools, there’s new approaches to what we already know and want to pursue as researchers in our own best interest and also in society’s welfare and also in this case, animal welfare. And I would like to just briefly refer to the concluding remarks, and come back to your statement on corrected measures, which used to be a punishment to inform the animal. Well, this is not what I want you to do, but since there’s something else, how can we make them realize that? From my own work with horses and natural horsemanship approaches, and also again, I’m a dog owner. I’ve come to realize that the natural horsemanship approach is based on observing how horses communicate with each other. And when it comes to corrective measures, a good observational set up is mother to child or mother to pub or child animal? I don’t know. There’s an umbrella term for crossfishes and how mother animals correct their children. Have you observed anything like that that you can apply in your research for growth? And also I find it on the other end, fascinating how adaptive many animals, and especially domestic animal species have become to read our ways to communicate and to learn words which they can’t speak themselves and learn to differentiate between. Okay. That’s what the human wants me to do, and that’s a no like no means no kind of thing. Okay, maybe that’s two questions. But first of all, can goats learn to differentiate between yes and no or good and bad, or have you learned to adopt behaviors and corrective measures that you’ve observed in the goats to be more animal and goat friendly in your approach?

Christian: What we most often want to do is to not really interrupt the behavior of the goats in the group. So that’s not really a corrected measure, because most often the experimenter is just the outside observer, sometimes in the experiments interacting with the animals in a controlled manner. When I refer to potential punishments, it relies on the fact that the animal has to learn over the course of the experiment that something is not rewarded or is even punished, for example. So I should avoid going there. So there’s a cost to go there. And this is particularly relevant. For example, let’s think about a cognitive bias approach. They usually have a rewarded situation and a non rerouted or punished situation. One is on the left, the other one is on the right side, and then you will have a position in the middle, and you want to see how the animal reacts, whether it has an expectation that this is rewarded or whether this is punished. So you need to train the animals beforehand that one position is rewarded, the other one is punished. So we do not really want to imply corrected measures in the usual husbandry routine or something like that. It might be rare in it at some point because some of the goats can get quite nifty and try to eat your trousers and your clothes and nibble on this and can get really well eager to get rewards from you. But usually we do not try to interfere with that. When it comes to your second question, in terms of goats learning from humans or goats observing humans and whether they can pick up any of this information, we have some first evidence or some first results that they actually can learn some special information from humans. We need to at some point, of course, try to replicate this and see whether this also holds true in other contexts. And we have also some studies that show that they can actually given

previous interactions with humans, that they can also interact with humans in a way that we might have expected to be the case for dogs, let’s say five or six years ago, which we did not really expect to see in farm animals in particular to this regard as well.

Let’s say we all know from dogs, when you put their toy out of reach, they start looking at you and alternate the view between the toy and you, which we indicate as humans, as a request for help or request for assistance. We were actually really a little bit surprised to see really strong behavioral responses from goats that look almost the same. So when we put the food out of reach so they can’t reach it themselves, they at some point start looking at humans as well. It’s not as interactive as with dogs because they have way more mimic options. And this is not the case for goats, but they show these gay alternations, for example as well. So there might be way more behind these human farm animal interactions than we might have previously believed.

Jo: Yeah, thanks for sharing that it’s quite insightful, surprising, but maybe not surprising because if we think about it, we all share this planet with thousands and tens of thousands and trillions and millions of animal species, from insects to bugs to whatever. And especially when it comes to vibrates and mammals, we are very closely related, but also to be able to interact in this world and to observe each other like who is friend, who is foe. Of course, there needs to be some empathy capacity in various species to learn to read and also to learn to interact with different species. But it’s good that we are making progress and getting insights into what’s possible and actually some research data on these topics. So thanks for sharing that observation as well.

Yeah. Thanks very much for this conversation. I’ve learned a lot. This is really exciting. Again, we will link all the articles and references mentioned in this conversation. And Christian, is there anything else you want to share from your research or anything that’s in preparation to be published regarding Open Science and animal research? I mean, you mentioned there’s the paper of those preprints coming soon. And also with your actual on topic research topics, what’s the next chapter, as far as you can tell,

Christian: As a closing message, if you’re working on Animal Behavior or Applied Animal Behavior, I would really be grateful if you could have a look not just at these articles that I mentioned, but in general at Open Science and how this can actually improve your own research and help you as a researcher as well. In terms of my personal outlook, we are, as I mentioned before, trying to establish a new behavioral paradigm for goats. It’s new for goats, not for all animals, where we try to rely on looking time and looking duration to video screens. So if you haven’t seen it yet, my Twitter handle is goat sets there. So I’m trying to stick to this promise and I hope I can deliver a lot of goat videos with this new paradigm as well. With goats looking at the different videos stimuli and hopefully we get better insights in terms of their preferences for certain stimuli or how they anticipate upcoming events for example

Jo: As much as we are trying to decrease our screen time goats are going to increase theirs at least to some extent to give us new insights. Thank you very much, Christian.

Christian: Thanks for having me, Jo, on this podcast.

Jo: See you all soon again, on this channel.