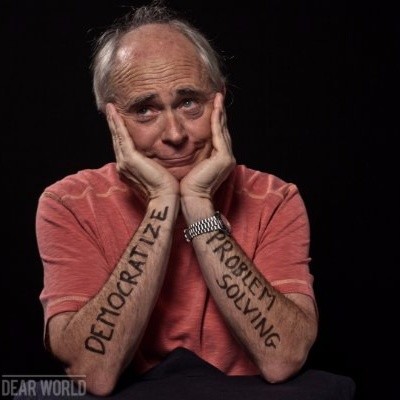

Richard Jefferson is a molecular biologist, social entrepreneur, inventor, open information systems proponent and innovation system strategist. He founded Cambia almost 30 years ago, as a means to democratize science-enabled innovation. He works on “Solving the Problem of Problem Solving”

In this series of episodes, Richard talks about his journey into molecular biology, social entrepreneurship, and innovation for societal as well as globally beneficial impact.

Bridging Academic landscapes.

At Access 2 Perspectives, we provide novel insights into the communication and management of Research. Our goal is to equip researchers with the skills and enthusiasm they need to pursue a successful and joyful career.

This podcast brings to you insights and conversations around the topics of Scholarly Reading, Writing and Publishing, Career Development inside and outside Academia, Research Project Management, Research Integrity, and Open Science.

Learn more about our work at https://access2perspectives.org

Richard Jefferson is a molecular biologist, social entrepreneur, inventor, open information systems proponent and innovation system strategist. He founded Cambia almost 30 years ago, as a means to democratize science-enabled innovation. He works on “Solving the Problem of Problem Solving”

He discusses his journey into molecular biology, social entrepreneurship, and invention with Jo in this podcast.

More details at access2perspectives.org/conversations/a-conversation-with-richard-jefferson/

Host:Dr Jo Havemann, ORCID iD0000-0002-6157-1494

Editing:Ebuka Ezeike

Music:Alex Lustig, produced byKitty Kat

License:Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

At Access 2 Perspectives, we guide you in your complete research workflow toward state-of-the-art research practices and in full compliance with funding and publishing requirements. Leverage your research projects to higher efficiency and increased collaboration opportunities while fostering your explorative spirit and joy.

Website: access2perspectives.org

To see all episodes, please go to our CONVERSATIONS page.

In the 1980’s, he started a biological open-source movement and later, the Biological Open Source (BiOS) Initiative, which was the world’s first patent-based commons. He founded The Lens 20 years ago and today, it is the world’s largest free, open and secure platform of science and technology knowledge that enables new and different people and institutions to solve critical problems, ‘Informed by Evidence, Inspired by Imagination’. The Lens Collective Action Project builds bridges and removes roadblocks to all innovators.

As a scientist, he developed enabling technologies; reporter gene systems (e.g. GUS), and microbial, plant, biomedical technologies. He did the first field release of a transgenic food crop (1987), and worked extensively in life sciences and agricultural innovation in Asia, Africa & Latin America with the FAO, the CGIAR and the Rockefeller Foundation.

As a fellow of the Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship, Richard Jefferson participates in many World Economic Forum events, including many times as a panelist and speaker at Davos and other meetings of the WEF, and was for four years on the Global Agenda Council for Intellectual Property, and four more on the Global Agenda Council on the Economics of Innovation.

His specialties: Social Enterprise, Patent Informatics, Climate Change, Open Access, Open Licensing, Innovation Policy, Innovation System Reform, Molecular Biology, Microbiomes, Plant Biotechnology, Agriculture, Global Development, Food Security, Enabling Technology, Complex Biological Systems, Evolution and the Hologenome. (Source: Richard Jefferson’s LinkedIn profile)

Personal profiles

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5352-4498

Websites: lens.org, cambia.org

Blog: blogs.cambia.org/raj

Twitter: HoloGnome

Linkedin: /in/richardajefferson/

Wikipedia: /wiki/Richard_Anthony_Jefferson

Name your (current) favorite song and interpret/group: – Borealis, Mike Marshall & Darol Anger (The Duo)

Related

Springer Nature and The Lens partner to accelerate use of science to advance solutions to global challenges, London | Canberra, 10 November 2022

TRANSCRIPT

Part 1

- Go to Part 2

- Go to Part 3 (coming soon)

Jo: Welcome, Richard Jefferson. It’s a great honor having you on the show, and we’ve been talking a couple of months ago, and I just wished I had hit the record button then, but now we’re here together again. It’s a great honor having you. Thanks for joining.

Richard: Thanks a lot, Jo. I appreciate it.

Jo: So, everyone, Richard is both the director of the Lens, which you might have heard me talking about quite a lot not only recently, and also the founder and CEO of Cambia, which is an overarching organization of which Lens is one of the sub organizations, that I may say so, and other projects and initiatives. And you started off as a molecular biologist, and we’re here to stretch over and tap into 35 years worth of experiences, wisdom, and lessons learned to share in this podcast. Let’s see how that goes.

Richard: Quickly, Jo. I promise I’ll speak really quickly.

Jo: It’s like double speed. So instead of speeding up as we listen to this, you might want to go half the speed.

Okay, so where should we start? Like, maybe how about 35 years ago? What did you say?

Social entrepreneurship and the kind of work you do today.

Richard: Of course, I’ll cover the first 30 years of those 35. Pretty quick, actually. It goes back a lot. Believe it or not a lot further than that. I’m 66 now, and I’ve basically been a molecular biologist since I was 18. And my focus, which shaped a lot of the work in the subsequent 40 or 45 years, is on methodology. I’ve always been fascinated by and drawn to the development of tools, of methods that allow other people, not just myself, to ask and answer questions, to solve problems, to do interesting things. And it’s by no means altruistic. It’s a joy to create. I think of myself more as an inventor than a discoverer. There seem to be fairly two discrete chasms in science. One you fall into in which you love discovery. Many, many, maybe most scientists by far are in the discovery. They love finding things out. And then there’s a small number of us who utterly love finding out how to find out. And so that’s been my draw. And so all during my undergraduate and my postgraduate studies in Boulder , Colorado, I was involved in inventing technology, inventing science that would allow inventing scientific tools to allow us to ask more interesting questions or more germaine questions that I thought were relevant at the time. So the beginning of my work that ultimately ended up forming Cambia and the biological open source movement in the eighties and nineties and the patent Lens and Lens and all of its work. And the reason I put a lot of my science aside, like Hologenome theory, is because I ended up going to a place called the Plant Breeding Institute in Cambridge for my postdoc. I had funding from the US. NIH to go there and basically to develop plant genetic engineering, which wasn’t a reality at the time I had grand visions of how we could use the technologies I wanted to invent, which were Heuristics gene fusion technologies that would allow you to visualize when and where and how much of a gene product is being made to understand developmental biology. My PhD was in developmental biology of the worm, seen in rapiditis and I was fascinated with how a plastic, an environmentally responsive system like in plants outside in the real world would respond where it wasn’t a strictly regimented developmental program. So I moved to the Planet Breeding Institute to work for the first time in agriculture, in agricultural biotech in its infancy and adapted the tool that I’d invented when I was in Boulder as a graduate student to work in plants. And it worked stunningly well and it opened up plant genetic engineering for the first time. No one could engineer plants before that. Then with this new tool it became not only possible but comparatively easy. But there was a congruence of several features in my life at that time that caused the birthing of Cambia and then later on, the biological open source. When I went to the Plant Breeding Institute in Cambridge, it was one of the only places in the world that combined agronomy and classical plant breeding with molecular genetics, the new fashionable element of biotechnology. It was very rare to find that combination in only a few places. The Max Planck Institute in Cone CSIRO in Australia here and PBI Plant Breeding Institute. Anyway, it was a very exciting time to be there. But what I discovered very early on was that the vast majority of the grad students and many of the postdocs were from what was then called the developing world, the global south. They were from India, Africa, Latin America, Asia, South Asia, east Asia as well as South Asia, Eastern Europe. And this was their only bite of the apple. This was their chance to get into a mainstream fashionable lab and publish a major paper or any kind of paper so they could get a job. And I was looking at this and finding there was a real ugliness to it because the group leaders, they’re all lovely people and I like them very much, but they’d fallen into this boys club, the elite, the colonial science, in other words. And these people were being used as bench fodder to do the grunty tissue culture work and the things that weren’t interesting to most cutting edge scientists. And they would do that and they would be thrown into that world instead of being at the decision making level. And that frustrated me and ultimately got me quite angry because many of these people were deeply committed to the contextual agriculture of their homes and places that we knew nothing about and they knew lots about. So that was the first thing that got me really, really troubled. And the next thing the next thing was that the molecular genesis were in a world of their own, incredibly exciting world, but a world largely devoid of context. We would reduce the problem into a model system and then we would work on that model system and not actually address the fact that by reducing it to a model system we had eliminated the intrinsic variability. And it’s intrinsic, it’s not extrinsic variability, it’s part of the system. It is a complex system in the real world and by turning it into a complicated system and then controlling the variables we study bullshit. And it turned out there were great agronomists, soil scientists, plant breeders, crop physiologists in that institute, at the other end of the institute, where I started to go more often and hang out. And I discovered there was this wealth of opportunity. These were people of generous spirit that were not being asked what are the important questions that were not being consulted on? How should we structure an experiment to ask the question or answer the question or solve a problem that really exists in the outside world? And this was also frustrating. So these two frustrations were very, very large to me that we had this large, largely untapped resource of dedicated, contextually aware people, this large untapped sense of expertise in fields that were uncomfortably complex to us. And then there was the third element. This was the third element that joined all these together and that was as an inventor, I had brought this technology forward that I was convinced was going to open up plant genetics biotech for anyone who wished to do it. Well, I don’t tend to write much in scholarly literature. I just don’t enjoy it very much. And so what ended up happening is that the rumor mill started. And when the rumor mills started, it gets around that I invented this tool and we genetically engineered a crop for the first time. And I remember a colleague of mine, when I was working with them, had a letter from a very famous professor in the United States saying to that colleague, hey, I heard the rumor that you, that colleague, haven’t been using this cool tool. Send it to me and we’ll collaborate and get some papers in cell science, nature, what have you. And this was taped over the bench of that colleague and he was going to be sending a bunch of the samples that I brought with me from Colorado and that I’d adjusted and modified and I saw this and it was really the final turn. I just couldn’t take much more of this. And so I tore that letter out and said, no, he’s going to get it at the same time as everybody else. I got sick of the old boys club and the colonial aspects of it. I didn’t think that was a productive way forward. So I then took a couple of months off and sent out, I don’t know, 510, 150 samples of the DNAs that I developed and the gene fusions I’d invented in the DNA sequence. And I did write instantly, in the course of a few days, a 40 or 50 page users manual. And I sent it out to hundreds and hundreds of labs around the world long before I published it, just by getting their names from a magazine called Plant Breeder, Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. It was a little non peer reviewed rag. It was a quarterly, sort of a newsletter. And I had found a friend of mine in Athens, Georgia who had found a copy of the mailing list from all the members $25 and you remember and everybody in the world that cared about plant biotechnology from Pakistan to Purdue, Beijing to Berkeley, they were all in there. And I said, okay, there are five or 600, something like that. So I made five or 600 padded envelopes and filled them all with these ten or twelve tubes in a whole user’s manual. And I sent it at the same time to all those labs before it was published, before any aspects of that were out, thinking that, okay, this is an open thing. Now, that was in 1986, seven thereabouts. And another Richard in a different Cambridge was doing a similar thing with software. That was Richard Stallman. I didn’t know him at the time. It went on to become the Free Software movement that morphed into the open source movement through some substantial changes. So I had been driven by similar frustration. I don’t know similar frustration, but by frustrations as it is that closed systems that would propagate a hierarchical and in my view, a scientifically backward view of the world that did not embrace context. And if the tools were available to everybody at that time, my naive idea was we would see hundreds, if not thousands of locally relevant biotech enterprises that would develop improved crops based on local small enterprise capabilities. That was my naive vision. Well, it did change science almost immediately. The big crops in the world. Within weeks or months of getting this in their lab, the big crops in the world started to become genetically engineered, transformed, as they called them. And when it’s open, it’s open to everybody. You can’t sort of be kind of open anymore. Then you’d be kind of pregnant. And amongst the people I sent it to, besides labs all over the developing world were also in the industrialized world. Friends of mine who worked at a company called Monsanto at that time, not the evil Monsanto. It’s a big company that had been working on plant biotech for a long time but had never genetically engineered a crop. And I remember a friend of mine who later on became quite a good friend, found that this just showed up in his mailbox at a company called Agracitus in Middleton, Wisconsin. And it was exactly the tool he’d been needing. And within a few weeks, he’d got this first transgenic soybean under contract in Monsanto, and soon thereafter in a battle of the Titans. It turned out that ultimately the multinationals got the first mover advantage and dominated global agriculture because of openness. I thought what? What did I do? And it turned out over the years that I discovered that by providing the last piece of a jigsaw puzzle to an entity that had already done its homework, it had lined up the foundational germ plasm, the marketing, the crop physiology, the target. They’ve done a huge amount of work to think about what the outcome was that they wanted in industrial agriculture, which is fine, that’s what it exists. I’m not saying they were evil by any means, they were just trying to solve a problem in industrial agriculture and make some money. But they’d done all the work. They saw the big picture, and this was the last piece they needed to pull it all together as a complete picture. They did that and they dominated global agriculture for 1520 years. And that was exactly the opposite to what my intention was. So there was I sending it out with the best of intentions, with my birkenstocks in hand, sending it to everyone in the world outraged by the colonial science that was going on. And I too did not understand how you make a product. And because of that, I stepped right in it. So in that case, I learned early on that it wasn’t about science. It was about all the other components that have to be coordinated to get an outcome that you want. You don’t form a business with just science. You have to have all sorts of other things, including intellectual property. So, anyway, that’s when I quit the plant breeding institute. Ultimately, I did that. I did the first field trial. I learned a lot. I also learned a lot about the failings. And I joined the United Nations as their first molecular biologist, I guess I’d be in 1989. And then they hired me to set up Cambia. But a lot of complexities I ended up learning a lot, but realizing the UN was a huge bureaucracy that would be a terrible tool to get an ambitious institution going, whose job was to invent technology to make other people’s capabilities more realizable. So anyway, that’s the beginning of why I started Cambia. And I ended up starting it in Australia, because first I always wanted to go to Australia, and I loved clean air and good sense of humor, but also it was in the same time zone as half the world’s population. And the Rock Photo Foundation gave me my first grant to troubleshoot their rice program, mostly in Asia. And so I wanted to be in the same time zone. I had friends here. It was a spectacular scientific and agricultural research environment at the time. So I moved here for a year, maybe about 27 years ago, actually 30 years ago now, how time flies.

So I’m taking a breath in between in case you want to stop me and say, well, that’s nonsense, Richard. The basic story was I stayed the course, thinking that inventing and providing good science to scientists around the world was going to change the world in some interesting ways. I cared a lot. I ended up spending a huge amount of my time on what might be considered artisanal or small farmer agriculture worldwide. I still have the fungus between my toes from all my time in rice paddy. I’ve never shaken that. And I learned so much from farmer field schools, from the idea of decentralized biodiversity being a very important part of a resilient system. I learned so much and at the same time I was still trying to develop tools that would work within those contexts, develop new ways of thinking and new ways of working. So the whole genome theory was something that developed fairly early in my career, recognizing that there was no entity that I could see in life that wasn’t a complex amalgam of microbes and a eukaryotic scaffold. And that informed that breakthrough in my thinking, informed my thinking about innovation systems and how, in fact the flexuous complexity was a feature, not a bug, and we had to celebrate it as such. So as we did this, I realized after a while that inventing new technologies that worked around intellectual property barriers was going to be critical. So I guess the next stage in the evolution of what went on to be biological open source, even though it started it by sending out all those vectors which changed science but did not in any way change in a positive way economic outcomes for anyone that I cared about anyway. So we discovered something else interesting that was captured. And this is a huge issue that science doesn’t like to deal with. Science is a phenomenon as a profession and individual scientists do not want to deal with, and that is corporate capture. It’s trivial to take science, whether it’s open or closed, whether it’s proprietary, published or a free manuscript, and say that you’ve done your part and you wash your hands. It’s like Verna von Braun. Von says, how could it go up? Who knows? Fails to come down. That’s not my department, says Verna von Braun. But in this case, the publishing of science is just the beginning of a long journey to impact. And the challenge is that publication can often be captured and often is captured by anyone that has done their homework, as Monsanto had done, or that has intellectual property that can then capture the use case of that science. If you don’t consider those things, then you’re not really serious about science getting out into society. It doesn’t mean that intellectual property is necessarily bad by any means. It doesn’t mean that companies that do their homework are bad by any means. But it does mean that there is absolutely no truth to the idea that openness in science gives rise to a socially positive outcome unless we consider all those things, unless we see them all. And what I discovered early on was that it was completely opaque. No one in the public sector understood the patent system. No one understood the massive intellectual property SCAIn of rights and ambitions that were driving much of industry and investment. And if you don’t understand it, you will play right into the hands of those who opportunistically capture public science, which is every company. And that doesn’t mean that they’re being evil. They’re just doing what we have allowed them to do. So any rage I would have about corporate control of science is really directed at the public sector for not having done its job well. Its job should be to experience the canvas and to make it clear to the world at large, including scientists, funders, administrators, regulators and companies, what the cartography into which this science is being delivered? If someone develops a new epitope that they think will be just wonderful for a vaccine without knowing or caring, or their funding agency not caring whether it can be turned into a vaccine or whether intellectual property from a third party will block it from becoming a vaccine or will be only incorporated in a high priced product, then that strikes me as a huge opportunity missed. And it means that much of science is basically just passively feeding a machine that they don’t understand. So that’s when we started with help from Rock Photo Foundation 22, 20 years ago, the bad lens.

Jo: Well, that’s quite a lot. And it also feels like the underlying thing that I’ve had all along. And I had a few conversations in the last couple of years. And what I also missed, often terribly missed from the open science discourse, is the limitations of open science. I tend to always give at least 30 minutes of thought for participants in my courses of where should science not be open? And it doesn’t end with sensitive data of patients that take part in a medical research project. But there’s many reasons and some others who also added to the question just now for research not being open. And I think the biggest misconception of the open science, some kind of movement where the open aspect is desirable, but more important is really the fair approach, where fair means findable accessible and operable and reusable. And accessible does not necessarily mean by anyone who has access to the Internet, but that is traceable. The whole workflow is traceable, like calling for transparency in the process. And again, transparency doesn’t mean that everything has been disclosed from the beginning, but it needs to be traceable back to the research idea and how the research was conducted in the first place, with what ideas in mind as an outcome. We opened up Pandora’s Box for discussion points here, but where I wanted to go is basically what I also started incorporating in my research project management lectures is for researchers to have a stakeholder analysis. And that often brings a lot of insight for the eligibility researchers who had not, who kind of vaguely knew who might be beneficiaries of their research projects and potential outcomes, but then to have them on their minds and then they thought as the design research approach before even getting started, going to put a whole other level of motivation and course into the project design. And I think, like what I thought and in some courses we actually did that to incorporate also a sweat analysis to anticipate what the strengths and weaknesses are of the research question and the potential outcomes. And like in the conversations that I have here and there, I always emphasize the responsibility and accountability the researchers have with conducting certain types of research and having to be responsible to actually anticipate that their outcomes might be misused by whoever or used for other purposes than intended just to really assess if a research question is ethical to pursue in the first place. And we have many famous examples in history, one of which is the work of Maurie Curie and Einstein and those guys which eventually led to the development of the nuclear bomb. But there’s plenty of others. But then what I always get in a response like no, you can’t expect that from researchers, let alone early career research. That’s way too much responsibility to even think about. But I think to be in such an elite clap of people and professionals that the research arena prides itself to be empowered responsibility. And I would wish that most researchers are ready to take on that responsibility on their shoulders.

Richard: Well, the challenge is this first, what you say about open science is quite divergent from my observation before I go into a potential solution to the conundrum you’ve raised about responsibility and researchers at all stages shouldering that responsibility which is associated with the incentives and the reward system that they get from their funders. We’ll come to that in a moment. But first, let me tell you a best little anecdote that I find quite useful in framing problem solving. A great physics professor of mine at the University of California when I was quite young, a member of a cup of coffee. I just adored physics. My brother was a professional physicist and I just loved it. And I guess if my brother hadn’t been one, I would have been older than me. He’d already sort of picked up that brass ring and it was my turn to do something different anyway. But his name was James Hartle at UC Santa Barbara, which has gone on to become maybe one of the greatest physics schools in the world. But at the time it was still very good, but not at that level. But James was great and he I remember over A Cup of coffee once, he said you got a hypothesis, don’t mess around with it. Just check it at the limits, at the zero. In the one case, try it at the extremes. If it’s going to fall over, it’s going to fall over at an extreme. And then once it does, throw it out and start over again. Start fresh, don’t waste your time. So I apply this pretty much constantly in my thinking, and it starts by saying, well, what is the outcome we seek? It’s not about saying what is the process we adhere to? Because we’re in a tribe that says being open is good. Why don’t we say why? Why are we doing it? What is the endgame? Is it because we want to publish open science? That’s stupid. If you want to say because we are on a planet that’s melting and we have maybe ten or 15 years before it’s the end of any reasonably recoverable civilization, then there you say, okay, now using the tools that I’ve learned, which is not about the molecular biology, that chemistry, it’s thinking tools, how would I use that to contribute to that? Now, if you start with that or if you start with a real problem, the efficiency of a solar cell, the effectiveness of a vaccine, the nutrition of a crop, almost anything you can think of that’s in the scope of scientific interest, you can then say, okay, what’s the end game? What is a successful intervention? And then work back from there to say, and what is in the way of that now? Is it whatever my tribe does? But if my tribe and my skills aren’t what’s in the way, why would I then motor on doing my thing? We have to sometimes change if we care about the outcome. And the challenge is we have professional structures that make that almost impossible. And so everyone goes back to the tribal behavior, the guild behavior, and they work within their guild and they build a virtue signaling system so they feel good about themselves. But strictly speaking, the system from the administrators, the policymakers, the funders, through to the institutional masters, through to the practitioners need to get a new way of looking at this that is outcome driven. We don’t have time to say, oh, but blue sky science is so great. It is. It’s beautiful stuff, blue sky science. But if we’re going to take the moral high ground of saying we’re trying to fix the world, then we have to bloody do it. And that means we have to start with an outcome that is attractive. If the outcome is that we see dozens or hundreds of new enterprises worldwide that are exploring new engineering solutions to electrical storage, well, then that’s an outcome we can live with. We say, okay, how do we do that? Well, the short answer is we have no mechanism to do that because public sector science per se is a comparatively new phenomenon. And it was never a designed phenomenon. It was just put together from spare parts and put some money into science with the idea that, oh, and then good things will happen. Well, what happens is, of course our science goes out and then we let the market forces select from that science things that can make products. Now, that’s not a bad thing at all if there is an alternative and if there are ways where non market forces can do that, but that’s where the public sector has dropped the ball. So what ends up happening, Jo, is that science goes out there and it’s like throwing stuff against the wall. Now, those companies that sense that one of these out, let’s imagine that it’s a vaccine candidate, they sense that this could be really useful. They’ve done a lot of homework. They have manufacturing class, they understand quality control, they understand how to do clinical trials. They look at that, they say, yeah, now it’ll take us x years and it will cost this much money. And if we do use that science, that’s fine. And that university wants to screw us with some licensing fees, which is antithetical, really, to what I would love to see happen. But that happens, okay? And so we do this and they say, okay, why would they do this cumbersome expensive process unless it’s for a market response. So there is a market signal saying comparatively rich people have this disease, there’s a market signal, they’ve got money, and we can then invest all this money to take this piece of science and use it for that disease. Not this neglected tropical disease, not this other problem, because in fact, there is no market for that. So this is a feature of letting market forces dominate. Now, market forces are not a bad thing, but they need to be both a regulated and a competitive environment where there are non market forces. So if you have weak market signals, meaning diffuse beneficiaries, as in climate change, almost everybody benefits from the improvement, but no single person benefits. That’s a classic conundrum of the commons. Now, if you look at that and you say, well, how can that harness for outcomes? It cannot until we see the scope of capabilities that must be aligned to get that outcome and we mobilize them. So you’re talking in fact, this goes right to what you were saying, the early career researcher, when faced with the impossibility of considering all these both ethical and practical issues. When I started explaining in the early days of the patent lens, we were the very first global patent search facility that was open and free. And 22 years we’ve grown and grown and grown and integrated with scholarly work to the point where by far the preeminent public facility to understand innovation knowledge. Public sector didn’t want to know it was in the too hard basket. They just didn’t want to know because there was no mechanism to care. So we started to develop this premise of innovation. Cartography the idea of. Mapping the innovation system around particular domains so that you had to care because you’d be embarrassed if you didn’t consider these issues. So my sense is the end game is not to focus on one thing like batteries or vaccines or what have you. It’s to focus on what is wrong with the innovation system that makes it so close to impossible. To do innovation for market failures, to do innovation for crises of the commons. Because we are living in the only time in our human history where we can see the end of our species if we don’t do something different, really different. And so we have to do it by changing the public sector. The private sector can be changed too, because public regulation is a very effective tool if it’s done well. And most companies like regulation that’s clear and transparent because they can work within that. It’s only when it’s opaque and capricious that they don’t. But the public sector needs to develop this. Now, I used to use the analogies of the Apollo Project or God forbid, the Manhattan Project as ways the government and industry and political imperative could get together and solve problems in a coordinated way. But recently I had a conversation with a colleague in the Netherlands and I had this AHA moment talking to him, realizing that the very existence of the Netherlands may be the very, very best example of public private civil society coordinated action against an environmental threat. The Netherlands only exists now because companies and government and all of society worked together to keep the North Sea at bay to have a country. The only way you can do that with engineering might be unprecedentedly hydraulic. It’s just an incredible achievement the Dutch have done. But they’ve done it with complete civil society support, complete government support, complete industry support. And they did it basically to forestall an environmental catastrophe which is the loss of their country. Now, that is an interesting example and I want to study that. How did they manage to mobilize that? Because it was probably an acute problem.

Jo: They’re literally underwater.

Richard: Well, exactly. When your feet are wet and it’s salty water, you know, you better work fast together. Now, unfortunately, we are the frogs on a boiling planet. And as it boils and we all talk about it and we all talk, somebody else is going to do it. Somebody else. So will Elon Musk save us? No, we have to reform the public sector so that we can innovate the entire space that’s needed. So the way I think of this and the way we in the lens are thinking about it imagine a rainbow bridge, Jo, that we use in our visuals. A bridge with pylons, each one a different color. One would be civil society, one would be governments. So the civil society would be the amplifiers of public need. The sea in which this bridge is embedded or the water is public beneficiaries, public outcomes. The first is civil society, an amplifier of that need. Second is governments, which is a facilitator. It should be dealing with these things. Then of course there’s the explorers, which are the scientists, the scholars that are trying to understand the scope of the nature of the issue. There are those who are facilitators enablers, so providing key services, whether those be legal services, contract research, whatever is necessary, manufacturing. And there are businesses, of course, which are builders of things, they make things. There’s not one thing in our lives that we touch, do anything that hasn’t gone through some form of business. All of these have to be joined by a suspension bridge of action. OK? To get a product means you have to coordinate elements of each of these regulations, of manufacturing, of marketing, of research outcomes, of scaling. All of these things have to be coordinated to get an outcome. It’s just a fact. The only one the public is doing much about is funding science and then saying they’re going to do regulation. And they do. Sometimes without seeing the canvas, the full scope of what’s necessary in a particular field, they cannot make a timely and informed decision because what we need is something that is inspired by imagination but informed by evidence or vice versa. It’s just wishing something doesn’t make it so. Here’s the way we think of this. In each of these Pylons, let’s say science or research and academic research, let’s say academia is one of these pillars that make part of the bridge. Well, even within the pillar, then the knowledge gap vertically is horrible. You have the data itself, the syntax, the metadata, then you have the copyrighted knowledge artifacts meaning and then the synthesis of that knowledge artifact into modern, progressive, new understanding. And each of these has a guild of practitioners, each one of them putting a rent extraction on the migration of knowledge from the early data through to practice. Okay, so there’s rent, rent, rent, rent, rent, rent. So it becomes very inefficient, but even more and more perniciously. That’s the one that has open access and open metadata and everybody that’s great stuff. We’re involved in that too. It’s good, but it’s by no means enough. Because what happens is, yes, you can actually improve that Pylon, but until that’s joined to the others, you get no effective bridge and you get no outcomes that we urgently need, that everyone urgently needs. So what’s the key? Each Pylon, whether it’s intellectual property here in law or science or marketing or regulation, has its own guild, its own guild of expertise, its own guild of data, of knowledge, of impact. The challenge is they are opaque to each other, they don’t share common norms. And basically the only way you get this to work is when businesses at great expense have their own department of research and their marketing head and their head of legal and their head of intellectual property and they have to get in a room and have their heads beat together and come in pursuit of a paycheck. So they solve the problem. That’s expensive, it’s slow, it’s cumbersome. So our job is to make it cheap and easy and accurate. So the idea is, if that becomes a norm, the interplay between the reason we started with patents is because it’s the largest non-copyrighted body of knowledge in our human history and it still is. So we host about 130,000,000 patents from 100 countries and we sew it together with the scholarly knowledge. We worked as the only collaborator of Microsoft Research, Microsoft Academic for seven years with Quantum Long and his team to develop what we do with our meta records and scholarly analysis and we’ve fused it in with the intellectual property world as all fully open data. We’re doing the same, we hope in the near future with legal and policy documents globally. The idea is to make these pylons, not to break these silos because silos have real value. Jo senses quality control elements. It’s not perfect, it has real problems and it’s game able, but it’s valuable in its own way. So we want to make them permanent and more transparent to each other so partnerships can form. At the very outset. When you talk about researchers saying a research project, where do they come up with this? They come up with this because other researchers on the peer review panel say gee, this is interesting. They say, oh, that’s interesting. The people who say they’re driven by curiosity have utterly no honesty about what makes them curious. There’s a billion things to be curious about why those things turn out. If you see that the things you could be curious about would have a higher probability of feeding in to a very substantial outcome that really makes a difference to people, then wouldn’t that allow you to still have the fun, but to be rewarded for doing something that had a better probability of working with a partner towards an opportunity, in a trajectory towards an outcome? So innovation cartography means that in any given field we map the intellectual property, the policy, the science and in a dynamic aggregate way. And that’s the key with open data where we have such common cause with the metadata world, the open data world. Because the only way to make aggregate knowledge is on the basis of what is known before. But if that knowledge is limited to a discrete view you don’t build. So the need for in a sense an evidence driven Wikipedia focused on every single one of the hundreds or thousands of different topics that need to be developed and turned into products and outcomes and policies and practices would make it necessary that funding agencies consider these things. So instead of saying I’m going to fund Jo Blow to do good science, we don’t have time for that. Our planet is in worse condition than the Netherlands was without the dice we are cooking. We don’t have time for business as usual. If we map it, the government can say, let’s say the Department of Energy of the US. Government with several billion dollars to spend, instead of saying, well, we’re going to spend it at this university or that university because it’s really good stuff and just hope that somebody picks it up.

Jo: Yeah, this is just because we just went through the week of nobel prizes. I know some of these laureates and admire their work, but really, do we have time for this? Like celebrating work that really has no applicability to the urgent issues that we’re trying to solve this very moment.

Richard: If you believe the science that science is about. I mean, every professional academic likes to say they’re evidence driven. If they are and they take a deep breath, they realize their children can never be scientists unless we do something about it. There can never be another academia. There is no tenure for a 23 year old. They will not be a 60 year old tenure professor because we will not have civilization in 40 years. We simply will not. We have to do something different. And innovation, cartography, in my view, is the best way the open data and open access and open anything community can work by becoming more sophisticated and actually respecting the different silos. How many scientists do you know think that marketing is important? Almost none. They hold it in contempt. Oh, those are just marketers. And yes, even with a vaccine, if it isn’t taken up and enjoyed and used and part of a public practice, it fails. So what good does it do to invent a cool epitope for a vaccine if it doesn’t turn into a vaccine, if it doesn’t pass regulatory compliance, if it doesn’t pass trials, if it doesn’t get desired, let alone accepted? So behavioral economics, do they have a role? Yes. Behavioral sciences, yes. But so do respect for business, respect for regulation, respect for each of the different silos. And if there’s one thing I can tell you, academia has none of its respect for anything outside of academia. Fine, personal extravagances. But generally as a guild, it is deeply embedded in itself more than the others. You can’t have marketing without having business and science and everything else. So the marketers will say, yeah, we really respect the science, but we want to market. Science likes to live inside its own walls and it has to mature instantly. And the best way to do that is not to talk to scientists about it. I failed. 25 years of my life was wasted with biological open source where everybody said, oh, what a great idea. We got the cover of The Economist and Nature and everything else on February 10, 2005. We must have had, when we launched it, probably 50 or 6100, 200 pieces of press in 40 languages, all about this biological open source. It was a total failure because it largely embraced academics. It said, this is what we’re going to do. The academics came onto our Bioforge site and after two years we shut it down because not one had contributed a substantive change. Not one, because they love to talk about it. But to actually change the thing, they need an incentive and a rewards scheme that’s different. So that’s our point of intervention. I love most of the academics. I know they’re my friends, but they can only work within this guild if the thing that drives the guild and feeds the guild, which is generally public money, has the insight to give them the rewards that allow them to behave according to their moral imperatives. So if we can provide innovation cartographies to the governments that are under pressure to deliver real change, they can do so by also changing the metrics by which academics are judged. So we’ve developed with Nature originally Nature index new measures of academic appreciation. One called Inform for the International industry and Innovation Influence Mapping. So this is a new area that’s really tangible to the open community because it’s all based on open metrics instead of closed metrics like the stuff that comes from Clarivator Scopus. And it’s really exciting. What’s interesting about that is that it can show that scientists that have been receiving no respect from their ears have been very influential in industry. And that’s not a bad thing. It’s a wonderful thing. I remember finding out that there was one fairly mature scientist at UC Davis. It’s a very famous agricultural school. I have many, many friends there. I spent a lot of my life giving talks and hanging out with friends that they’re brilliant open access scholars, brilliant hologenous scholars, microbiome scholars like John Eisen. He has to be both of those things. Lovely people there. Well, I remember reading about or when we did this new tool. We worked with the NIH and CrossRef and others to scrape out of the patent literature their citations to scholarly literature. Well, virtually none of these researchers knew that companies that were patenting things were reading their papers. Well, patenting is not always a bad thing. In fact, many times it’s just a signal that they’re making stuff, which is not a bad thing at all, is it? So what ends up happening is you say, well, let’s look at the citations for UC Davis. And we did that. We built a citation graph and we looked at all the productivity. And then there were plenty of people that didn’t do all that well, and they were probably relegated to crappy offices in some outbuilding without air conditioning, which in Davis was really bad. And we looked a little more carefully because we did a ratio of those that were heavily cited by scholars versus those that were cited by patenting organizations. And we discovered something fascinating. There was this one scientist who had close to 10 citations from a private plant breeding company because his work had influenced the development of new varieties in a very substantial way. But other scholars didn’t give him a blank. So there was this person, the dean of his faculty would have thought he was a loser, giving him the worst office, giving him the worst teaching load, but in fact, in terms of impact on agriculture and society, he was a rock star. But there was no way to recognize and reward that. So when this new informed thing came out and we’re doing it again with nature to get it out there, it’s a terribly exciting tool to begin to change the mindset, to realize that there are ways to not just look retroactively at what did someone do, but to say, how do you make a good partnership? How do you make a constructive partnership? That’s not just about bucks, it’s about productively working together to see an outcome. And of course, if the outcome is one that’s in a market response, that’s fine. If it’s not, then the government can intervene. So what foundations and governments are supposed to be good at is amplifying weak market signals with their dollars. That’s why we have a public sector, if everything could be thrown into the market forces, we wouldn’t have any commons. So we need public intervention. But it should be insightful and it’s not. It should be, it should be targeted and it’s not. But we can fix that with innovation. Cartography so that’s what has been obsessive over the last 20 years, developing the Lens. About ten years ago we changed it from patent lens to lens as we migrated into merging all the research literature with all the patent literature and turning it into open metadata with really good analytics and really good user experience. So for 22 years we specialized in the user experience with the Lens. I mean, I look at other sites which are data driven, they’re embarrassing. It’s not about the data, it’s about the people making decisions. And it has to be about the culture of people making decisions that comes first. Unfortunately, the vast majority of academic data scientists and data scientists, fascinating people doing good stuff, but when they try to make a product out of it, they forget it’s not about the data, it’s about the decision making process, which is by human beings. And if they think that a user experience is something like marmite on toast, you spread it onto your data, you’re completely wrong. The UX should drive the data, the user should determine the data. Because if you do it that way and you consider the human and creative joy, the generative joy of coming up with new insights and you drive it through the human joyful experience, you get something very special.

Jo: Isn’t the data DNA of the product?

Richard: Yes, the DNA is in me too. But you don’t interact with my DNA, you interact with me. Jo: Alright. Okay. Got you. I’m just trying to point out that the data is important. We’re struggling with researchers to document the data, to substantiate their results.

Richard: We’re talking about very different things. If you’re talking about research data as opposed to data facilities, our approach is that we’re trying to get decision making capabilities in the hands of people who need it and we’re trying to have them informed by evidence. So that means we have to think about the people first, the data second. The data is critical, but it’s not enough. You can’t do data first and say, oh, let’s see if we can adjust it for people. You start by the end game, just like James Hardel told me, think about the outcome. The outcome is a wise, insightful decision by a policymaker in the EU or by a policymaker in China. An insightful, evidence driven decision to bring the financial tools, the regulatory tools at their disposal together to make a partnership and a trajectory to an outcome. That’s the end of the game. We want a good, meaningful, evidence driven decision by a human being with their own human imperatives. That’s really, really important.

Jo: So you’re asking that academics and researchers should follow more of the entrepreneurial product design approach? When I think about the research.

Richard: No, not at all. Because until they’re rewarded for doing that, why would I tell them to do that? It’s the wrong thing to do. But no, that won’t work until we change the incentive system. I have a lot of sympathy for academics with a good heart who would love to say, well, we have this design approach, unless it’s informed by innovation mapping, they don’t have the tools. They simply don’t have the tools. So we have to create, build a process and a platform which allows these innovation maps to be created. Now, once they’re created the idea of a thoughtful research community and institution getting together and saying, hey, this is the state of play. This is the cartography around the chemistry of solar cells, or what have you, this is the cartography. Now let’s talk. Where are the points of intervention? You see, if you ask an early career, mid career researcher to change what they’re doing, if you also don’t change their reward system that allows them to get a job the next year or a grant the next year, nothing will change. You’ll have some well intentioned people who find themselves, as soon as they are on their third postdoc saying this has been a waste of time and we don’t want to dishearten people. We want to give them the tools and their paymasters in both in the institutions that hire and promote them and in the funding agencies that empower them. We want to give them the tools. You can read from the same script and come to an evidence driven decision. So I don’t want scientists to change without the knowledge of all the people in what amounts to the supply chain of their work, also understanding what’s needed. So you need that.

Jo: Yeah. I don’t think we would change the scientists rather later on in the game. Yes, but what I’ve observed is that early career researchers, when I asked them, why did you become a researcher? Why did you take on this journey? And there in the first year, they’re still very happy to answer the question, well, this is that in the second and third year they kind of lost it because they find themselves in a rigid, competitive, numbers driven game they never sign up for. And that’s where we would have to change or really encourage them to embrace their values and remind themselves of why they cut themselves into this academic circumstance.

Richard: I’m going to push back on that. I don’t think we need to remind them. We have to give the people that have made that institution rigid.

Jo: That’s what I was getting at.

Richard: No, I’m going to push back. You got to get the priorities here the instrument required if scientists or any human is to have a heartful, generative decision process. Right now, academics are largely trapped. For some years, I was quite disdainful of academia because of their largely narcissistic tribal bullshit. But it turns out that that’s imposed on them by the tribe. And the tribe is not people, it’s an institution, and it’s a series of institutions. And that’s our point of intervention. So we have to say, why are the institutions constraining this? It’s because they and the scientists and the other parties to the innovation system cannot see a solution that involves all of their participation. Once that solution can be seen in innovation cartography, we can actually have government funders, institutional gurus or management and scientists and manufacturers and business people and lawyers and policymakers getting together to solve discrete problems that are incentivized by a variety of the levers of government. So this is critical. If we make it if we make it effective enough, it also means that market forces can operate on a weaker market signal. So our secret is not that we’re saying, oh, government will solve everything, but if we target governments, it opens up an efficiency that also lets the private sector deal with smaller margins and smaller markets, which is essential to actually getting effective innovation happening. So the private sector will benefit from this innovation cartography enormously. It’ll be able to make products at a lower price point more quickly and with lower risk. There’s a term we use at Cambia at the lens. We call it mapping ports. Ports like the ports in an ocean. And let me explain what I mean by that, because it’s a very useful term to hang things on. There’s one other term I’ll come to at the end. I like having a visual for everything I do, I think visually. So if I were to tell you, let’s imagine you’re a sailor and you’re in Hamburg and there’s a river that goes out to the sea and stuff. And I say, well, okay. There you are in Hamburg. Would you mind mapping the entire North Sea for me? And they say you’re crazy. I can’t do that. I have this time. I’ve been too busy. Oh, sorry. Could you map me the entrances to the river? Oh, yeah, I can do that. I mean, it’ll take me a few days, alibaba. But I know how to do the depth soundings and I know that area. So the port is can be mapped by someone who understands that, okay, if I tell someone to map the world, they won’t be able to. But if I ask them to map the thing they know something about, they can. But if I ask people all over the world to map the things they know about, you get ultimately a map of the world. Now, the reason the word port is so interesting here is that for us, it stands for the four key elements that make for an innovation reform partnerships. It’s first, nothing is done by itself. And I don’t mean collaboration between scientists. I mean getting outside the rainbow bridge. So partnerships, opportunities, critical. Because if people don’t see opportunities for themselves in career advancement and money, if they’re a business person in solution spaces, if they’re a policymaker or a funder from the government, if they don’t see opportunities, they’re not going to do it. And they have to be sticky partnerships made by ongoing opportunities. But then there’s the third danger zone risk that’s the R reports. Partnerships, opportunity, risks. No matter what happens, everyone has to consider risk. Whether you’re moving capital into a project or you’re moving your own personal and emotional capital into a project, if you can’t map and decrease known risk, you won’t get it to work. And the last one is every solution that we seek is dynamic. It’s going to take time to come. That means we have to have a trajectory. And that trajectory can’t be locked in like a fiveyear plan. It has to be dynamic. You have to change. New things are published, new science comes on, new manufacturing capabilities, new crises emerge. We have to change on the fly with evidence. So mapping partnerships, opportunities, risks and trajectories is a matter of dealing with the knowledge corpus that’s there, but focusing on a particular element, a particular domain. Now, the other aspect I’m going to leave you with because otherwise I’ll just talk to you until your day is gone, is all of this is not about science. It’s what we call steps. So I told you there are a couple of terms we use. We use ports and we use steps. What is steps? It’s what I think we should be talking about in a time of climate crisis. We should not be talking about science. We should be talking about science and technology enabled problem solving. So that’s steps. The end game, the James Hardel game is problem solving. We have to solve a problem. If the problem is inadequate resilience in our soils, if the problem is carbon emission from blah blah blah blah we’ve got a problem. Science and technology enabled problem solving is another way of saying evidence driven problem solving. But it harnesses the generative joy of the scholarly and research process which is a critical element. It’s a very special place in this bridge because it’s the only one that generates totally denovo knowledge. Civil society is very important for the same reason but we have to harness that. So science and technology enabled problemsolving steps is what it’s all about. And the goal is to use mapped ports in every domain which requires open data, it requires linked data. So those data mavens who might be listening to this, there’s a huge role for you in this. The idea of getting harnessing existing practices. We can’t tell people to change unless we make it easy for them to do so and a reward for them to do so. Okay? So you have to identify our targets, which are the incentive system and the reward system. And that will be done when you have no choice but to see the outcomes that are pursuant to your decisions. So that’s our goal with cabbie in the lens and as we go to scale in the next year or two, it will be to take this into a dynamic process where anyone, anywhere can map and share or not share as they wish their mapping of the domain that they wish to see a problem solved within. So that’s my I’ve skipped over 25 years of the learning that gave rise to this. But you get the idea, the initial idea scientists can fix things proved to be wrong. Then the idea of the biological open source that oh, when scientists band together and get patent free this and that, it’s going to say it did nothing constructive. What’s going to be constructive is when we map incentives for people. We map opportunities, partnerships, opportunities, risks, trajectories. And that can be done now, it couldn’t have been done ten years ago because we didn’t have open scholarly metadata research metadata. We do now and we have deals that we make with companies that allow us to ingest their data and spew it out as open data which is really cool. And this is a critical step forward. So that’s where I am with this. I really wish all my academic friends were free of the yoke of the largely ignorant funding agencies. And I say ignorant not as a pejorative. They’re ignorant because they simply don’t know if we make it possible and necessary for them to know. They can make better decisions and they can reward people who work towards the outcomes they desire. They can’t right now. So here we are, crisis of our species history and we’re just behaving the way we did in 1970. Big deal.

Jo: We also have an autonomous. Tag. I would like to chime in with the UNESCO Open Science recommendations where they say open Science also has an opportunity, an obligation to interact, exchange and engage with other knowledge systems. They were mostly looking at indigenous knowledge and scholars at risk, but also maybe not explicitly in the current recommendation as proclaimed. But I was thinking why not as a cooperate knowledge system? Because what I think scholarly digital repositories can serve and are still heavily understood. As much as we’re trying to interlink data and research output items with each other within the academic ecosystem, there’s vast opportunity to also include or find linkages with copyright research data;

Richard: Absolutely

Jo: That’s not happening at scale just yet. We were approached with a question about this like can we also upload our annual reports as an NGO? Can we also upload our corporate reports because we have data to offer to academia and we might also want to make use of research data, so why not also the other way around? There’s tremendous opportunity for knowledge exchange across the sectors which as we just said and agreed upon, is a dire need thereof. So why don’t we use or is this basically also where you are at the Lens and other initiatives that you pursue? It’s basically what you do as well, patents.

Richard: Exactly that. I mean basically when corporate research is done see, you’re talking about research, but there’s so much more. Companies have vastly more than their research outputs. They have capabilities, they have phenomenal capabilities that may manifest in infrastructure. They may be manifested in knowhow about manufacturing, scaling, and quality control. There’s so much in businesses at all scales. A baker knows vastly more than I bake bread in my kitchen. They know how to do it day in and day out, correctly and efficiently. There’s no how embedded in business. So the formal knowledge corporate, if you’re talking about corporate research, almost all corporate research that they wish to disclose is in the patent literature. So we’re already dying to do that and it is available. But, you know, you say, oh, but it’s so desirable to have that. I got to tell you that almost no academics outside of summon chemistry and engineering ever read the patent literature. It’s not copyrighted. There’s hundred million records. Do they read them? Absolutely not, Kai, because it’s not my department. So is it really that we need all this corporate linking? No, not really, because they’re not going to pay attention to it. What we do need is linkages to many of the informal data that you’re talking about, gray literature data and other things about the corporations to discover their capabilities. This is important and it’s on our radar. It’s something that utterly needs to be done. For sure, absolutely. But when we’re resources, as all organizations are resource limited, we have to prioritize and we say, well, where are the lowest hanging and most impactful interventions we can make. We’re the ones that, on a timely basis, galvanize people’s interest in this. Certain intellectual property is intriguing for two reasons. One is that to get a patent, you have to, even though it’s gamed quite a bit, you have to teach, you have to disclose what you wish to have protected. So the patents, by their very nature, in principle, have to teach you something that was not known before. If a patent is granted, it has to be new, nonobvious and useful. Now, the system is gamed constantly. But that said, there’s an enormous amount of knowledge that academics don’t want to know about. So when someone tells me, I’m fascinated by X, I say, well, have you read, you know, the 400 patents about X? No, I’m not interested in patents. I say, but they know about X. They know a lot about X. There’s a lot of patents about X. Oh, but that’s just a patent. You know, most science that’s published is probably wrong, and most patents are probably wrong, but there’s a huge number of them that are not. And if scientists won’t read patents, I don’t have any time for them to say, oh, but I really want to solve this problem. No, they don’t. They want their solution. So I think that they’ll link all this linked open data to corporate, this and that. Yes, it’s already there in a lot of ways in patents, and academics don’t use it, and they won’t until the incentives change. That’s as simple as it gets. You can talk about them all, UNESCO recommendations, everything else. No one follows those recommendations. They talk about them, they have meetings about them. The same people show up at the meetings, they have the tea and coffee and afterwards go to dinner and talk about how wonderful it is. But nothing changes with that. Unless we change the flow of money, the nature of the regulation, and do it by incentivizing the actors to change, it’s not going to be, it’s just going to be virtue signaling, and that’s the death of good intentions. When you get together in a tribe and talk about how wonderful you are, nothing changes. You gotta make it change at the level of the incentives, in my opinion, which of course, nobody has to listen to.

Jo: Well I do.

Richard: But you have to know, you have to because you’re on this, because it’s your podcast, you have to.

Jo: I think what we also both share is a passion and obsession about global equity, and maybe particularly in a research context. So how do you think patents can also serve an opportunity for equity on a global scale, like what you see in the non typical patent owning countries?

Richard: Are you familiar with the term that was prominent in the open source wars in the early days before Microsoft became the good guys? It was called FUD fear uncertainty and doubt. And the idea was that corporations that had proprietary software and did not want to see the open source software succeed would plant the idea of FUD fear, uncertainty, and doubt so that people would not believe that they would not adopt it, they wouldn’t use it. And ultimately, it proved to work really, really well to use it for certain key elements. And so the fund, however, was a tool to make people not want to do things well. It turns out the vast majority of even current patents in Europe or the United States, the vast majority are not patented in the vast majority of countries. You know what that means, both legally and ethically? Anyone in those countries, anyone in those countries can make businesses and products based on the information in that patent as long as they sell within countries in which those patents are not enforced. In our system, we have a trivial way to do that. You can ask, okay, find me all the COVID vaccine patents that are not present in sub Saharan Africa. And the answer is, almost all of them are not there. You can say, show me the solar cell patents or the electric vehicle patents or whatever else that are not present in Brazil, that are not present in India, that are not present in China.

Jo: That’s a game changer is saying out loud here, okay? I mean, also what the media made us think like, oh, there’s four countries in the global South I cannot afford, and then there’s patents and those evil.

Richard: That’s just bullshit. You don’t need a license if it’s not patented in your country. And if you’re not selling into a country in which it is, patents and copyright could not be more different. Now, if you took notes in this podcast, okay, let’s imagine you jotted some notes. The moment you jot those notes down, you instantly have copyright over them. You don’t have to apply for it because I assume you’re in Germany right now.

Jo: Yes

Richard: Okay. Germany is a party to the Baron Convention on Global Copyright, which means the moment you create a generative work that might be considered suitable for copyright, strictly speaking, I think a podcast could be copyrighted. Of course, instantly you have copyright without applying for it in over 120 countries. I can’t remember the number, but it’s 150 countries. It’s a lot. And any country that’s signatory to that has to accept that ripping off your podcast without your permission or basically copying your podcast without your permission is in violation of copyright law because there’s a treaty that binds your national law to an international norm. Copyright does that. So if someone takes if you write a book and someone just starts xeroxing it and sending it all over the developing world, strictly speaking, that’s piracy. There’s no doubt about it. If you give permission, that’s fine. You choose as the copyright holder, as the generative individual that has created that work, you can choose. That’s why Creative Commons was a real important breakthrough, because it makes it easy to choose how you wish to share Creative Commons. You can be as proprietary as you like or as open as you like, and there’s lots of flavors, but it’s your choice as the creator. With patents, that’s not the case. For a patent, you have to apply, and if you don’t apply, you get no coverage. If you apply and it’s rejected by a patent examiner, you have no coverage. If you don’t apply in country X-Y-Z whatever, you have no coverage. And it’s also time limited. The copyright is for a very long time, thanks to bloody Walt Disney, you have a very long copyright protection patent. It’s maximum these days, it’s a few gray areas called evergreen, but maximum of 20 years from the date of application. So if you apply for a patent and it takes you three or four years to get it, you might get 15 or 16 years, but then there’s no jackbooted patent police. The other thing is that people who don’t infringe a patent are not illegal. It’s just exposing you to civil liabilities. Remember that civil and criminal law are really different. Civil law, the penalty is money. Criminal law, that’s usually incarceration. So if a company chooses to use a patented product without telling somebody, are they breaking the law? Well, they’re breaking patent law, but are they committing a criminal act? Probably not, but they are subjecting themselves to real potential liabilities. And businesses hate risk for good reason. They’re usually gambling with somebody else’s money and they can’t afford to do that. So patents have so many restrictions, and the fund that’s been produced by huge patent holding companies and huge patent holding countries is enormous. Most of the developing world, most of the global south, 120 and 130 countries have almost no patents in force at all. Zero. And you can check it in the lens. It’s an extremely good, easy thing to do. You can pick any subject you want, look for the patents, then say, show me where they’re filed and show me where they’re granted. The short answer is almost all the developing world. The patent system is God’s boon for innovation, but the FUD convinces them otherwise. So if there’s one thing they should do, it’s realizing, hey, there’s nothing better than the patent system. If Morocco wants to copy everything ever invented by Dupont, I’ll bet you there isn’t a single Moroccan patent held by Dupont. And if they want to plan to do Dupont stuff, as long as they don’t sell it into a country in which Dupont has those patents, sure it’s legal, it’s ethical, it’s what the patent system was designed to do. You know what the word patent comes from?

Jo: No. It’s from the Latin word pateri, which means to lay open the original purpose of the patent system. The modern patent system was pioneered by my great uncle Thomas in the United States in 1793, and he was the first patent examiner. He was the third President of the United States, the author of the Declaration of Independence, but he was also the founder of the US patent system and the patent examiner himself. Imagine how tough it was to convince Thomas Jefferson that your cotton gin or whatever you’d invented was really new and it was not obvious and it was useful to get a patent. But the purpose of the patent system was to pull things out of secrecy into public knowledge. That was the purpose. There were no journals at those times. How would you know when someone had invented a new chemical compound or a new spring for a chronometer? How would you know they would make their own chronometers and they’d never tell you how they did it? But Thomas Jefferson and the whole brilliance of the early patent system, which has been really gamed horribly since then, but the concept was brilliant. It said, we’ll give you a limited period where you alone can benefit from that, but you have to tell everybody about it from day one so they can learn from it and build on it, so they can possibly improve your invention and each can prove to each other. It was the original Wikipedia, the patent system. So what ended up happening was, of course, later on you realize how it can be a game. There’s all sorts of problems with an administrative bureaucracy, but the premise was brilliant. It was to make things open. So right now, every patent in the world is not enforced in Burkina Faso. I tell you that for a fact. I have 130,000,000 patents in our system, and there’s not one of them that’s enforced in Burkina Faso. I’m just picking that name at random. But, I mean, you could pick a huge number of countries. None of the patents stopped them. All of them lay open. But FUD fear, uncertainty, and doubt was planted by corporations and by big patenting governments to try to make people not realize the power of that as a teaching tool. So we’ve been, for 22 years, the principal public facility, the secure public facility where anyone can start looking at that and mapping it on the fields of their expertise and classifications. So you want to talk about something they can do right now? They have to show that they want to do something. They really want to do something. Read the patents. Academics won’t, but people who want to build something, they’d better. Good news.

Jo: Wow. Let’s get to work. Jesus.

Richard: Yeah, I’m at work.

Jo: I was speaking to the listeners.

Richard: I’m at work. What do you mean?

Jo: Well, thank you so much for sharing all of this. I’m running into time issues here. I have to jump on it now. I have to jump in another meeting. But there’s like, at least three big discussions, not points, but arenas I would like to explore with you, if you don’t mind.

Richard: You bet. I’m happy to help. Anyway, I just want to reinforce the issue that I have lots of respect for all the pioneers of the Open X movements, where Open access, open data, open source, open science, open I’m not sure about open science because I can’t hear anybody’s definition that makes any sense. But all of these things require advocates and they require champions. I would just encourage them to expand their scope and not do too much virtue signaling. Recognizing that solving the problem of a male planet is a lot more important than feeling, like super, super important because I’m more open than you. And the other thing, the last point I’d say is business and government each are major sectors with their own cultural norms. And if we say, you’ve got to change, we might as well go home. What we have to say is, here is a tool by which, working within your norms, you can do a better job. If you look at it that way, you can see normative and practical changes happen. It’s not going to happen by confrontation. We don’t have time. Sure, you know, a lot of people have tried it with revolutions and what have you. It takes a long time to make change unless you incentivize it and make it more effective for their norms to practice. So our strategy has to do with that. And it’s really important to consider, for instance, open. We’ve got really tired of selling the lens as open this and Open that. It is definitely all 100% open data, and every single piece of our data can be inspected for free, without surveillance, without advertisement by any human on Earth. If you want tools, if you’re an academic, you get those tools for free. If you’re a company, we ask you to help subsidize this based on your size. If you’re in the Global South, you don’t have to worry about it. However, and this is where it gets really intriguing, what we can say is that pitching it to corporations which license us as open is scary to them. Because the most important aspect of company culture is confidentiality. Because competition drives all of business is driven by competition and confidentiality. So when we say open, they get scared. What if we just say you’re in control? Or it’s your choice. It’s your choice whether you share or not share. Because our data is perfect for proprietary applications, it’s also perfect for open applications. We don’t impose like the GPO, we don’t impose openness on the people who use our data. We say it’s open and we’ll continue to serve open data. If you want to internalize it in your corporation to do the things that your norms insist on to make a product, that’s okay, just help subsidize this for everybody else. But you don’t have to share with us. I’d like it if they did, but I won’t demand it. If we want to change, we can’t start by telling people they can’t be what they are. We have to make it easier for them to be better at what they are.

Jo: Like, I’m kind of an evolutionary biologist with molecular tools and I feel like what we’re building now in the open or fair, whatever knowledge system within academia and with access points to other sectors is really mimicking what evolutions does all along. Like to produce data, as in accumulating knowledge for individuals benefits, meaning survival of the fittest who are not given certain circumstances, but also providing reuse of the very same for other purposes and communities.