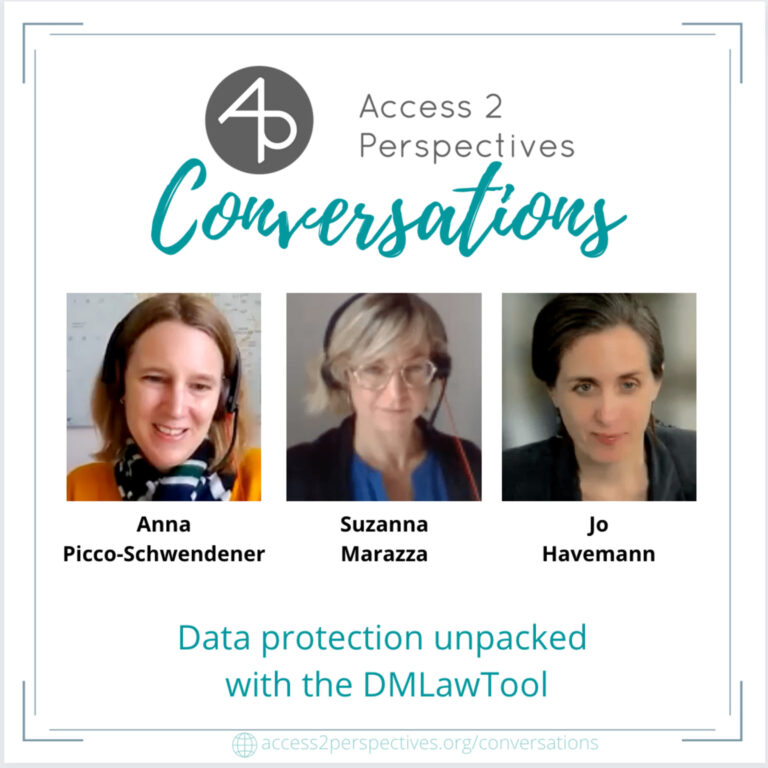

Anna Picco-Schwendener is a Postdoctoral Researcher while Suzanna Marazza is a Legal consultant. They both work at USI Università della Svizzera italiana, Switzerland.

They joined Jo on this podcast to talk about Data and Copyrights protection.

Bridging Academic landscapes.

At Access 2 Perspectives, we provide novel insights into the communication and management of Research. Our goal is to equip researchers with the skills and enthusiasm they need to pursue a successful and joyful career.

This podcast brings to you insights and conversations around the topics of Scholarly Reading, Writing and Publishing, Career Development inside and outside Academia, Research Project Management, Research Integrity, and Open Science.

Learn more about our work at https://access2perspectives.org

DMLawTool has been developed by the Università della Svizzera italiana (USI) in collaboration with the University of Neuchâtel (UNINE) within the P-5 programme “Scientific information” of swiss universities. The tool has been officially launched at the end of March, 2021, and is available to everyone for free from the CCdigitallaw.ch platform.

Explore all our episodes ataccess2perspectives.org/conversations

Host:Dr Jo Havemann, ORCID iD 0000-0002-6157-1494

Editing: Ebuka Ezeike

Music: Alex Lustig, produced by Kitty Kat

License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

At Access 2 Perspectives, we guide you in your complete research workflow toward state-of-the-art research practices and in full compliance with funding and publishing requirements. Leverage your research projects to higher efficiency and increased collaboration opportunities while fostering your explorative spirit and joy.

Website:access2perspectives.org

To see all episodes, please go to our CONVERSATIONS page.

Suzanna Marazza is a collaborator at Università della Svizzera italiana (USI)’s eLearning Lab (http://www.elearninglab.org) and as a legal consultant, she works on several projects dealing with digital law – ranging from copyright to data protection, especially within academia.

Both Anna and Suzanna work for the project CCdigitallaw (https://ccdigitallaw.ch/index.php/english) which is a competence center in digital law for Swiss Higher Education Institutions, doing workshops and responding to requests in Italian, German, French and English related to copyright, licensing and data protection.

They have also been able to develop the DMLawTool (https://dmlawtool.ccdigitallaw.ch), a software that aims at helping researchers in dealing with possible legal issues they might encounter during research data collection and management. (Source: Guests’ LinkedIn Profiles)

Personal profile

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-1196-2702

Website: ccdigitallaw.ch/index.php/english

Linkedin: /in/anna-picco-schwendener-b1a22216

Which researcher – dead or alive – do you find inspiring?

Anna:

Suzanna:

What is your favorite animal and why?

Anna:

Suzanna:

Name your (current) favorite song and interpret/group/musician/artist.

Anna:

Suzanna:

What is your favorite dish/meal?

Anna:

Suzanna:

On-topic questions

General introduction into legal aspects in (open) science

- Copyright

- Research Data security

- Personal Data privacy

Presenting the DM Law tool:

Part 1: Data protection

- Data anonymization

- Asking for consent and other requirements and processes for personal data protection

- Which license to apply to datasets? CC-BY or CC-0 ?

- https://www.gida-global.org/care CARE Principles

Part 2: Copyright

- Know your legal rights as the copyright holder of your work (manuscript and datasets)

- Negotiables and non-negotiables in a publisher agreement

- What legal aspects are important for the editor and why are they non-negotiable?

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berne_Convention

- https://v2.sherpa.ac.uk/romeo/search.html

References (related research articles)

- Lugano legal lab

- https://ccdigitallaw.ch/index.php/english/faqs

- https://www.humanrights.com/course/lesson/articles-26-30/read-article-27.html

TRANSCRIPT

Part 1: Data Protection unpacked with the DM Law Tool

Go to Part 2: Copyright unpacked with the DM Law Tool

Jo: Welcome to another episode of our podcast show here at Access 2 Perspectives, and warmly welcome Suzanna Marazza and Anna Picco-Schwendener from Switzerland. It’s a pleasure having you here. Welcome.

Anna: Thank you very much.

Suzanna: Thank you.

Jo: Just to contextualize, we didn’t actually meet in the summer, but two of us were presenting at the Swiss Open science Summer School this year. And I think I’ve also seen you in the program of the previous summer school two years ago where you presented amongst legal issues, legal challenges for researchers, which we’ll talk about today as well. And then you developed the DML Tool, which we’ll come to talk about later on. So stay tuned, listeners. This is something that’s really come in handy for your research and will make your life very much easier when it comes to legal considerations about your research, which was really confusing and frightening, actually, also for me when I was a grad student. But yeah, starting off, how about would you like to share about yourselves where you work and what brought you to work on legal aspects of research? Would you like to start? Anna?

Anna: Yes. So thank you very much for inviting us to this podcast. We are very happy to be here. It’s like the first time we do something like this, so we hope to be clear. So maybe just a few words about myself. I’m a postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Communication, Culture and Society of the University del Italiana. This is the University of the Italian speaking part in Switzerland. And among others, I’m teaching two courses, one related to E- government and the other about online communication design. And on the other side, I’m also working as a scientific collaborator for our university’s E-learning lab. And there I’m in charge of the competence center in digital law, which we will maybe introduce later on. A little bit more in depth. Yeah. What else? I’m also part of the operating unit of the Lugano Living Lab, which is a lab for integrating technologies and savoring innovation provided by our city in collaboration with the university. And yes, I’m actually originally coming from the German speaking part of Switzerland. I grew up in Surrey and TSUK and then moved to Ticino, the Italian speaking part, in order to study communication sciences. And then I stayed here. I worked for several years for a steel trading company. Always in the field of I.T, I was responsible for the Internet. And then I moved back to the university to do a PhD. My PhD was about studying social dimensions of public large scale WiFi networks. I analyzed the case of municipal and community wireless networks. And then while working at our university, we work on many different projects. One project was about building up this competence center in digital law within the Elearning lab. But I think we can say a little bit more about this later on. What else to say? I have been living here in Lugano since then, I have three kids, two boys and a daughter. The boys are 14 and 16, and the daughter is nine years old. And they keep me busy quite a lot beyond my job. And yes, I don’t know, do you want some more information?

Jo: That’s great for now, and I’m sure we’ll hear more about your work. And maybe if we would add, like, what made you interested, what sparked your interest in legal aspects and research. Like how, like myself and others, I know we were just scared to not to death, but, like, quite intimidated by anything legal when it comes to consider that, or it seems so far away from what we want to engage in as researchers.

Anna: Yes. So, I mean, I didn’t actually plan to do anything about legal aspects when I started here. It was thanks to a project we had with Swiss universities, which was about making this legal aspect mainly about copyright, more accessible to a non expert audience. So this challenge of providing training and also a little bit of advising, but in a language that is so that it can help be helpful to people who haven’t studied law before. And I think this challenge of actually translating this sometimes very complex language actually fascinated me. And also this idea of, like, my idea of law was like, this is something very strict, very fixed, and everything is very well defined, while I actually had to discover that, okay, there are some rules, but then on how to apply this really depends a lot on the case. It really depends on the context. So one of the most used answers by legal experts and also by us now, is like, it depends, which is sometimes frustrating for the people because they want clear answers. And for us, in order to be able to provide clear answers, we need clear cases. So the more specific people are, the more specific we can be with the answers, obviously, beyond providing the general concepts, which Suzanna will talk about later on. But it’s actually a very fascinating area, I would say especially also, our goal was applying these legal rules to the digital context. So in the world of the Internet, where pictures are labeled so easily, and people are not always aware of what can actually be done with this huge amount of material that it’s just one click away and available on the Internet.

Jo:I think a common misconception is that anything legal is restrictive, and it is, in a way, a resource to protect and to ensure authorship, acknowledgement of the creator of any image or text or data. But we come to talk about that, what’s the reasoning behind legal requirements? Yeah, it’s fascinating. Also to me. I recently learned also on the podcast about patents. Like, I had a totally different view on patents than being super restrictive and enabling monopolies, where the idea of patents in the first place was actually to protect and also share the knowledge, but protect from misappropriation and misuse.

Anna: I think this is really something. Also researchers are in this double role. On the one side, they are authors, they’re producing knowledge, they’re writing articles, and on the other side, they would like to reuse content that already exists. They are on one side users, and on the other side, they are authors. And I think that’s also what helps them to understand the value of the rules for the one side protecting, and on the other side, favoring reuse of material.

Jo: Yeah. Thank you so much, Anna. And Suzanna. Please let us know who you are and what brought you to work with Anna on legal aspects.

Suzanna: Yeah, also from my side, thank you very much, Jo, for inviting us. So, where to start? First of all, I’ve been working for the Content Center in digital Law, already presented by Anna. So I’ve been working for three years now and dealing with the issues that occur in a digital world so to say. The two main issues are copyright and data protection matters which are distinct from one another. They are independent, one from the other. But these are the two main law fields that must be considered in academia, in research especially. So I’m finishing my law studies. Actually, I’m writing my thesis now. I’m studying law in Como, which is North Italy. It’s close to the border with Switzerland. That’s why we study both Swiss and Italian law, which is very interesting because it gives a very open minded perspective of law. Because even if fiscal law and Italian law are similar, but they are also the same, they are also very different, one from the other, and the mentalities are very different. So it’s very interesting to be able to compare two different laws to different legislations. And so I’m finishing soon, hopefully. And my thesis is actually about giving an interpretation of finding a solution to permit open access in the sharing of cultural goods. So the goal is cultural heritage preservation and sharing of this knowledgement, where copyright very often gives a closed permission. It’s very restrictive. There is this, as you said, this monopoly, this exclusive right of the right holder, and it’s very difficult to share works protected by copyright. So there are different conflicts, different interests. On one side, intellectual property is part of the property rights guaranteed by the Constitution as well as guaranteed by many international higher acts. But at the same level, there are also other interests such as freedom of expression, freedom of research, freedom of education, the need for a society to develop, to be part of culture, to develop knowledge. So we need to find copyright law, and need to find a balance between these different interests. And so starting to work in this conference center and digital law here at University University, I started being really passionate about this topic, especially about copyright. And so I started really being interested in this whole field. So apart from working here also I also deal in this topic for my private interest. I’m also collaborating with Creative Commons in several policies and creating several policies in order to find a solution to be active worldwide to open up copyright. That doesn’t mean deleting all the rights of the right holder, but it’s about giving a more powerful space to freedom of expression and preservation of cultural heritage. Well, we will talk about that maybe later on. I don’t want to tell you everything now. So to say, starting by working for this company center, I started being really passionate about copyright. So that brought me to work in this field also beyond what is work, but also being part of Creative Commons and finding other possibilities and solutions to open up copyright. Apart from the competence center in digital law, I also work for the regional administration. That has nothing to do with copyright. It’s another field dealing with more criminal law. That’s it.

Jo: Wow, two huge areas of work you’re engaged in.

Suzanna: Yes, maybe too much, but it doesn’t matter.

Jo: Yeah, there was more an inclination of appreciation and amazement rather than criticizing. Thank you. Great. Super interesting. Thanks so much. So we talked and before this recording now we agreed that we divide the conversation into two parts, starting with data protection.

When it comes to data protection, research data, what is research data in the first place? Maybe we also have to define that and the different components of data, like metadata, primary data, secondary raw data. Some listeners might be well aware, or maybe we don’t have to make these distinctions talking about data protection, but in your work at the competence center, and also as you facilitate or inform researchers how they can protect the data, data sets that they decide to publish and share. But also maybe at what point does data protection come into play? Is it already necessary at the working level when you’re still processing the data? Or is it only upon the decision point where you actually want to release it to a wider audience? And does that audience have to be public? Or is that a protection already a requirement or a necessity to have at earlier stages when you share with a selected audience and not the general public online? So where you’re the expert, like, where should we dig in and how like, I live totally up to you how to frame the topic.

Anna: Maybe just one thing, maybe that could be useful for the audience. Maybe if we quickly introduce also what the competence center actually is and just to frame it a little bit wide actually we’re here to talk about this topic.

Jo: Absolutely, and then maybe we have…

Anna: And then we can move to data protection, if this is okay for you.

Jo: Absolutely, yeah. Perfect.

Anna: Okay, so just a few words now. We call it ccdigitallaw.ch It’s the competence center. In digital law. And the goal of this competence center is actually to support Swiss higher education institutions in dealing with legal questions, mainly in relation to new media, digital media, the digitization projects and technologies, and to raise awareness of legal risks. So what we are providing is mainly teaching, training and some advice to all kinds of people who are working within Swiss higher education institutions. This could be researchers, teachers, all kinds of administrative stuff. A lot of libraries actually come to us, but sometimes also I.T services and in some cases we also collaborate with the legal services of the universities. So how did we come to create this venture? So it has been created through a project funded by the program Scientific Information Access, Treatment and Safeguarding by Swiss universities already quite some years ago. And it is the result of a collaboration between different universities, our university, the University of Delas Vitregaliana, the University of Basel, the University of Nishatel, the University of Geneva and also the Conference of Swiss Libraries. The main challenge, I would say, for this center has actually been trying to find a sustainable business model. We actually at the beginning wanted to have a collaboration between these universities to continue the project. Also after the end of the funded project by Swiss universities, this actually became very difficult. So that’s why our university and specifically our Elearning section of our university decided to take over the work that we have done, especially also the platform. We have created a platform with a huge knowledge base about copyright aspects where we really try to explain the different rules, the different laws, in a more simple, in a more understandable language, providing a lot of examples. We have a vast FAQ section and so to maintain this platform and also to maintain and extend the service of training and of advising and I have to say now after several years of operations, we actually receive quite a lot of requests, especially for training and also for advising. And maybe the last thing to say about this, that is we are always operating before a legal problem occurs. We try to do this awareness raising. As soon as someone has a legal problem, we say no, you have to go to a lawyer. And we are not, that’s not our expertise. So our expertise is before we try to avoid legal problems. Appearing and coming up in a few words, I don’t know if it was clear enough or if…

Jo: It was very much. Absolutely and we also have the link to the competence center is also in the show Notes and the affiliated blog post to this episode. So listeners, please take a visit to the website of ccdigitallaw.ch and you’ll find a vast amount of information which is tailored towards the Swiss research audience. But much of the information we come to talk about is probably applicable in other countries. And the only thing that I think will also talk about is how copyright differs in various countries and what aspects of the copyright are universal, but universal doesn’t necessarily include every country on this planet, right?

Anna: Yeah, I think this is something that Susanna will explain later on, and I think this is a very important point to raise up now. So our knowledge base, all the information we provide through our platform is based on Swiss law. And as you said, there are many aspects that are similar in other countries, but obviously not everything. So be aware of the fact that the basis is the Swiss legislation.

Jo: And the DM Law tool that we’re going to present later on, as well as a tool for researchers to look at and to inform and get in. A quick overview, but also in depth insight around various legal aspects is also based on this, with legal requirements and consistency. And you also have a disclaimer for any visitor, like, please make sure that you also consider an international legal requirement. Cool. So that’s for tips. Thanks very much, Anna, for contextualizing and also thanks for both of your work and your colleagues in the competence center. I think this is highly needed for any stakeholder research to have easy access to an understanding of legal requirements and legal the baseline to conduct our work under. And it’s actually not so difficult. I figured it sounds intimidating thinking about legal stuff, but when you actually do, it has a certain logic to it. Let’s dig in. So, data protection, where should we start? What are aspects of data protection?

Suzanna: Maybe first, I would suggest starting by explaining what is the goal of data protection laws? Yeah, because what is protected is privacy is the private and family life of a person. And by misusing personal data, there is a risk of infringing private lives, privacy of the person. That’s why laws regulate how to use personal data. So laws are about how to correctly use personal data in order not to infringe privacy, not to infringe private life of the person, because the personal data are the instruments, the concrete instruments through which it is possible to invade it to infringe the private sphere. So it’s always about balancing again, as you said, it’s always about balancing several interests that are in conflict with each other. On one side, for certain services, for certain reasons, there is a need for processing personal data. But on the other side, there is respect for the private life of the person. So it’s always about finding the good balance, the fair balance between these two interests. And it’s very difficult sometimes. So before regulations, we were not really aware of how much big data, especially how much was the risk for processing big data in privacy infringing private spheres. So nowadays, these laws regulate, okay, if you have a reason, if you need to process personal data, for example, now, outside of the research field, if you need to buy, if you need to fly with an airplane, you need to book a flight. Of course, there are organizational matters. To organize the flight, you must give your name, surname and certain personal data in order for the company to organize the flight. Because it’s not like it’s not a bus. You just enter in and you go where you need to go. There is a whole organization. So in order to give this service, you need to provide personal data. And the company has to store to process your personal data for the service of the flight. But then keeping these personal data and using them for advertising or for other things, that goes beyond what was the service, what was the purpose for which you granted you released your personal data. Therefore, that’s an infringement of your private life because not because of the emails directly, but because of your personal data being stored somewhere and being processed by someone without your knowledge, maybe without your consent.

Jo: Can I add this one? Can I advocate for a second. And as a Navy question, so what’s the worst thing that could happen? And because in Germany, when I follow the debate about data protection, personal data privacy, most people think, well, I have nothing to hide, just don’t use my data.

Suzanna: Of course, yeah, you think, why is Google interested in my life? I have nothing to hide. Of course, okay. But on the other side, who knows? We have no idea who is behind processing personal data. So maybe at a certain point, first to say on the Internet, with this big data, it’s so easy to combine data sets. And you never know one certain data set, how it can be combined, how it can be matched with another data set, or in whose hands it can end up, and what can a certain person do with your data? So the worst case scenario could be there is a leak of data and someone in the world uses personal data for criminal infringement, for criminal behaviors, such as creating false profiles and taking data to do some frauds or to mislead someone in order to do certain frauds, that there are so many to convince someone to receive money, for example. So if I have certain personal data of someone, I can say that’s a very easy example, but unfortunately, it happens. I falsely say, like, I’m a member of your family, I urgently need money. And I convince maybe a naive person, an old person, by telling, but by knowing certain details of the family. So the person really very easily falls.

Jo: As you mentioned it, because that actually happened just a week ago to my mother. And then when she shared that, we found that it was not the first time somebody used her number, sending her a message, as if it was from me or the gender didn’t matter at that point, but she received a message from an unknown number. Oh, mom, imagine I lost. You don’t know what happened. I had to get a new number and I need money, please send it to this account.

Suzanna: Exactly. It could happen.

Jo: My mom reached, she thought, I mean, her immediate reaction would have probably been to follow through. But then her husband was like wait, let’s try the number.

Anna: That’s good. Obviously another very simple example is you publish on your Facebook or on your Instagram account some holiday pictures and you don’t really reflect on how much data with this you’re going to tell probably to your friends, but depending on the settings you have done on the social media, maybe also to a vast audience. So first of all, you say currently I’m not at home, so this might be useful information for someone who is interested in getting into your house. Or you tell people where exactly you are staying. You tell people what kind of hotels you’re staying in. So, I don’t know, maybe a five star hotel might tell people, okay, you can afford this kind of hotel. I don’t know. But sometimes we are not aware of how much information we actually disclose through images or through some very simple data sharing.

Jo: And then the geolocation is also transferred from the picture because on mobile phones smartphones are so smart. They also add the geolocation to the image information, the metadata of the actual photo, and then you post it on Facebook. And then Facebook knows this information. But also anybody who’s on Facebook can extract information from the image, right?

Suzanna: Exactly. There is so much information with only one picture that can tell you or can tell who is behind a device, who on the internet can tell so much information. Also, if you think of our contact list in our phone, we can see the prefix. Someone seeing the contact list can imagine what countries we are in contact with. That can lead to many, many pieces of information which are even maybe not really true. So it can really mislead certain judgments very, very easily and without thinking of the worst case scenarios such as the criminal field. Also big data, I think, well, again from these big companies, why are they interested in my very simple life? But if we multiply this by so many people, these big companies have a huge amount of data and they gain so much money with this big amount of data. With this big data. We use these services and social media for free. And we even share our emotions through social media. And whoever is responsible for this social media, they have a profit.

Jo: The other fear or threat might be, which was discussed extensively here in Germany, is that personal data might be misused also by health insurances. If they see from the data that we so easily share on social media that we have whatever health conditions and then that might lead to us not getting insurance and therefore not being able to afford any treatments that can actually be life threatening sooner or later. And this is already in a pretty safe environment where we think we’re pretty safe in Central Europe, but when it comes to countries or fragile states, the information sharing can actually lead to political persecution

Suzanna: and discrimination.

Jo: Yeah. So just to make a loop from the personal use and sharing of our data to how that applies in a research context, because in research with fair data and open data and to make research data relevant in the first place and reusable and reproducible, we want to add as much information as possible. But what we just discussed was true. For personal data sharing, there’s also threads and limitations and consideration and research data where we should, as researchers, be highly cautious. What is information that we need to add to contextualize the experiment and what is information that potentially puts the research subjects or people that we work with, patients and medical research often, or animal species that are being observed and are endangered by extinction or from extinction, might be at risk from poaching if we disclose the geolocation. So are these questions that come to you often, kind of how to make an informed decision, what information to add as metadata to a data set and whatnot?

Anna: Yeah, so it brings all data protection laws and foresees some certain principles which are first of all, if you process personal data, you need to inform the subject about what personal data you are processing, for what purpose, where are you storing personal data, et cetera. And consent is required. So the consent must be an informed consent. That means the person must be clearly informed of how their personal data are processed. Just to say, before a few years ago, our privacy policies were really unclear and very long and very hard to understand. No one would read privacy policies. Nowadays, with our newest data protection laws, it is required that privacy policies must be clear so that the subject can read it through and can really understand or pretty much understand how personal data are used and then after being informed, give clear consent. So it is important when dealing with personal data, also in research to have an informed consent of the subject and always keeping in mind this balance between, on one side, freedom of research, which also requires a certain processing of personal data and also to disclose the research. And sometimes it’s very difficult to fully anonymous research data, but on the other hand, always keep in mind not to violate the privacy of the subject. So it’s always keeping this balance.

Jo: Yeah. So would you say this is my take from what you said? Like it lays on the responsibility of the researcher and research team to make differentiation and have clear understanding of potential misuse cases over there?

Anna: Exactly, yes. First of all, when does data protection law come into play? As soon as you deal with personal data. That means if a person is identifiable then you need to apply well then data protection laws apply and you need to consider all the principles and all the rules. So it’s not enough to remove the name and surname of the person, but you need to consider and that has to be considered on a case by case basis. If someone reads through the research data or sees the research data, is it possible to anyhow identify the person or not? If it is possible maybe also later on through a matching with another dataset it is possible to identify the subjects. Then be careful. Consent is required and minimum personal data must be published, not what is not needed for the purpose of the research. If you don’t even deal with personal data, maybe there is some raw data or certain information about certain facts and not it’s even about people or it’s not possible to identify a specific person then there is no need. The data protection laws don’t apply. Anonymisation is very difficult if you have a bunch of personal data, maybe you have aggregated data and it’s not possible to identify specific people then that’s good. Again, personal data does not apply but you really need to evaluate that specific case. Even if you have aggregated data, maybe there is a few data that can be related to an identifiable person, remove these few data and keep only the aggregated data if you don’t have consent. Of course, if maybe there are certain people who are also happy to be heard, they’re happy to give their voice about a certain problem and they’re also happy to be again with respect to their privacy, they are happy to be part of a research and be part of finding a certain solution to a problem. Of course their consent is very important.

Jo: Yes, thank you. And when we now consider licensing the data for reuse also and to protect the data sets from misuse, I think both apply, right? Which is why we want to add a license. Is it that research data is where I feel I should know better at this point. But now with data sets it’s not as easy as with copyrights and the data sets are a different category as compared to images and anything creative and text. Because I think by default data is a public good, but you can protect it. Is that so?

Anna:There is no ownership of data. We cannot say they are private, they are public, they are who is the owner? There is no ownership as we know ownership as we mean it for like being an owner of a book of a computer or a mobile phone. There are these several rules, there are several laws that apply. So data is about a person, if there is an identifiable person and you need to respect their privacy, it’s not about ownership, it’s about paying attention or not violating privacy of the subjects the data is related to. Another thing is ownership in the meaning of copyright. So who is the right holder of the data if the data is protected by copyright? As you said, copyright protects artistic creations. Maybe it is possible that a data is not protected by copyright if there is no originality, if it’s not an artistic work. In that case, if a data, for example, a list of natural facts, maybe it’s not even protected by copyright, it doesn’t concern people. There is no privacy protection, there is no copyright protection that applies. So there is no ownership. In that sense, there are discussions about recognizing a certain kind of ownership, a certain kind of protection. But nowadays there is no protection apart from copyright and apart from well, privacy is about protecting the person, not the data itself.

Jo: It’s also because many data repositories only have CC Zero as an option to choose from as a license, which is because data is meant to be a public good, to be reused by other researchers in the center. But then the researchers often feel protective about it because they put so much work into it, basically their whole process.

Suzanna: Just be careful not to confuse licenses. And Creative Commons licenses are about how they regulate copyright matters, not other matters. Okay? So if we release a content, if we release data with Creative Commons license, we only say according to copyright rules, you are allowed, for example, with a CC Zero license, you are allowed to reuse this content, you are allowed to modify, to share, etc. But it’s about copyright. When you release a date under CC Zero license, you yourself, as a researcher, as the person who releases the content, are responsible that privacy matters are OK. And also other matters. There may also be certain commercial secrets that you need to consider, in case you also need to consider if there is a criminal law, et cetera. So a Creative Commons license is only about copyright. There is a very big issue right now because certain big commercial companies used images released in I don’t remember if it was on certain platforms under a CC zero license. So anyone is allowed to reuse these images. And these big commercial companies use these images also with faces, and they use these images for artificial intelligence recognition, to educate artificial intelligence recognition. But right now there is a very big controversy or discussion about more ethical matters. Is it okay that big commercial companies use CC Zero images to educate artificial intelligence recognition? And it’s difficult to give an answer because based on law, if there is a content, if the person that is captured in the image gave their content for their image to be uploaded online and to be released under CC Zero license, that means also the right holder of the image, granted the right to reuse the image for any purpose. That is what is granted in a c zero license. There is no law infringement. It’s more about but there is a problem. Some people are disturbed by the fact of their face being used for Ie recognition. So it’s more about ethical problems and finding a solution to do when releasing research data with a Creative Common license. Again, it’s about copyright. And you need consent. You need separate specific consent from the people subject of the personal data to permit anyone else to reuse such data, including personal data. Whereas if the research data are anonymized, then it is not possible to identify a person. There is no privacy matter, there is maybe only copyright matter if it is a world protected by copyright.

Anna: Okay, maybe, Susanna, Jo, you had this question about the ownership of data and all in data protection. We don’t have this concept, but we have this concept of again, in copyright, it can be protected if it is considered as a work. So, I don’t know, I mean, this again goes into copyright. Maybe we can discuss it later on when we talk about copyright. But also here, Susanna, please correct me. We have to distinguish what kind of data can actually be protected by copyright and can be considered a work. So a single data. So there are some characteristics which Susanna will explain later on, that work has to satisfy in order to be protected. And in some cases data, or especially data sets. So how data is put together, there is some creativity in this. So this might be a way to actually get the work the researcher puts in this. Now, you said the researcher actually feels that no, this is my data. I created it. I put a lot of effort inside it now, so especially the way they compose their data set. If there is some creativity, these data sets might be protected by copyright, but at least maybe you can explain better, Susana.

Suzanna: I suggest we keep copyright details. And also there is a European directive that protects a data set. We leave that for the corporate chapter, not to confuse it with privacy rules, which are really independent, one from the other. So it was just to say that it is important not to confuse. When we release the research data under a Creative Common license, we grant permission according to copyright rules, not according to privacy. It is implicit that when I release a data set under a Creative Commons license, I already took care of privacy event potential problems. So when I released a research lead on the Creative Commons license, I already have all the consents if they are needed. I already paid attention. I already evaluated that the data set maybe doesn’t include personal data. So I don’t even need to apply data protection rules. If either I have concerns, or I’m not dealing with personal data, I can release the research data under a Creative Commons license again, which regulates copyright matters. We will talk about that later.

Jo: Yeah, I mean the question of data ownership is like I often raise the question on my courses where I ask the students who do you think owns your data? And leading towards publishing the heck out of your research, whatever you can because you will lose access to your own research data. And assuming it’s your own, it’s probably not your own because look, in your work contracts or in whatever work agreement you have with institution university or the research institution where you work at, they might say there that whatever you generate as data and research output is theirs or not. And you may or may not be allowed unauthorized to take your research output with you. But then you have to physically make sure to also do that. And then also depending on if you’re a Stem researcher, depending on the equipment, maybe the equipment manufacturers also have a stake because it’s only due to their manufacturing that you’re able to generate certain kinds of data. Or your funder maybe the funder says the data is ours because we give the money and the funder can well be the taxpayer. So you better release the data because they pay for it. So these are all very much ethical questions or actual legal questions to consider because there might be places that the researchers are often aware of.

Anna: Yes, I totally agree. There are both ethical but also legal questions. It’s true. Very often the researchers are not aware of their rights, and are not aware of what is written inside a license. But again, that’s how data can be used. It’s all about copyright matters. So I will only keep it for later, not to confuse it with privacy. What we can talk about ownership and data protection is that again there is no ownership of our personal data. I’m not the owner of my personal data. So if I release…

Jo: I’m not the owner of my personal data? That’s new.

Anna: I’m not the owner of my personal data. Parents are not the owners of their children’s personal data. There is no ownership of personal data. First of all, data protection laws apply when processing personal data. And the term processing means everything. It means from the moment someone collects personal data, the moment the person is doing something personal could be the process of certain of anonymizing this, changing this, working with personal data go within the term processing, storing and then deleting personal data. Everything is included in the term of processing. So the laws, data protection laws say that all these rules apply when processing personal data. First of all, keep in mind from the moment you are collecting, you need to apply or the processor needs to apply data protection rules. So the moment I release my personal data to maybe, for example, a researcher who is doing a survey, I’m releasing my personal data, the researcher is processing my personal data. And it’s not about giving or it’s not about stealing personal data. It’s just about processing, it’s just about dealing with personal data and automatically applying all data protection rules, which are most important. It’s taking security measures to avoid leaks of personal data, etc. If I’m the subject of my personal data, I have a control over data protection laws guarantee the subjects they have control over their personal data. What does that mean? It’s the possibility of knowing or it’s the right to know who is processing my personal data, who is doing what with my personal data and controlling where my personal data is stored. That means I also have the right to ask, please delete all my personal data. And so these are all the rules, all the rights that are within data protection laws in this control. So it’s not about ownership, but it’s about controlling who is doing what with my personal data.

Jo: OK, that’s actually interesting. I hope it’s a little bit more clear. A little bit, but I need to wrap my head around but I’m getting there. Thanks for caring. Okay, I wanted to briefly, because this is actually a hard topic for me, the Care Principles was I don’t know if you’re familiar with them and I’m not sure if that well, after what I learned from you today already, I’m not sure if that’s the Data Protection Office. Again, I think it’s more of a copyright, but I would like to mention it here so that for the copyright edition of our conversation, we can maybe refer back to it. So the care principles are meant to complement the fair principles, find a better, acceptable and reusability of research data, which I think is also more I assume it’s also being more copyright related. Yes, it is.

Suzanna: Okay, privacy is included, but it’s not about it is indirectly related to privacy.

Jo: And now the care principles were postulated by indigenous community representatives who also happen to be researchers and being well aware of the preference of it and appreciating these, they figured well, when it comes to working with local or indigenous communities, all the ethical questions are not being addressed and answered like many of which we had in our conversation, not in western context, so to say. But there’s no such thing as individual ownership of anything. So copyrights, again, I think we’ll have that more in depth in the next episode. But just to mention that the care principles look towards collective benefit of the research data authority to control responsibility and ethics. And again like some of which we also addressed here in the data Protection section session. And would you like to add a few comments on this or later.

Anna: Just to maybe conclude to finish this data protection chapter? On a theoretical level, data protection is very easy because it’s really about first of all wondering if you are dealing with personal data or not? If not very well. You are avoiding many potential problems. In that case, it could be either your data are about natural effects or for example, Arts paintings. So apart from the authors of paintings of the Arts, there is no personal data and that’s okay. Or you deal with aggregated data so fully anonymized it is absolutely not possible to identify the subject. On the other side, if yes, you deal with personal data, content is required. Here in Switzerland, we have an exception which permits processing personal data for research purposes. But it’s really a very restrictive exception. So it’s better to always have a consent of the subject in order to use their personal data for the research. One thing is using data for the research, for example, doing surveys. And another thing, another specific concept is required to publish the personal data. It is possible for a researcher to collect personal data, but then at the moment of publishing, it is possible for the researcher to publish only anonymized research results. So there are these several steps and in each step the researcher needs to wonder if he’s still dealing with personal data and specific consent is required. And that applies. So this rule applies to any kind of processing of personal data. It’s always about I’m a researcher. I want to publish my research results within the institutional platform with closed access. If I publish my research results, open access, it doesn’t matter. Always apply these rules. Okay? Okay. So on the theoretical level, there is not a lot to talk about. I don’t want to minimize the subject, but it’s really about the theoretical level, the rules to apply, very easy. There are only a few of them.

Jo: But it gets very complex. As we also found in our conversation here today when we look at a specific research project and then to identify which other data points that actually contain personal data and to what extent and how far do we need to anonymize it to still be explicit in what we want to say with our data towards the results of the project. At the same time protecting individuals for their personal identities.

Suzanna: Yeah. So it’s really on a case by case basis to evaluate what is the solution to find this balance between the interests. One side, the research interest in publishing either the data set or the research results, or the research itself application, and on the other side, the interest of the subject of respecting their privacy. So if you think of health research, psychiatry research, it’s very difficult maybe to anonymize a data set survey or certain results. It would also not make sense to publish a research by completely anonymizing, because maybe you are talking about only a few cases that happened in the world. So maybe someone living in the same city of the subject, if it happens that this person reads the research or the content, the data is able to identify the subject because it’s only one in a million. So in such cases, it’s really very difficult to anonymize and to respect privacy if you don’t publish the research, it’s really on a case by case basis to find a fair balance between these interests.

Jo: Yeah. Thankfully, there’s also now tools available to an Aluminum data set automatically. I mean, there’s still a human factor that’s necessary. We also add these to the links. Okay. Yeah. Thank you so much for enlightening us on data protection. Yeah. I think the topic remains complex, but…

Anna: Agreed.

Jo: Well, very complex, but it really helps to explain the different aspects that come to play and considerations that are necessary to have and to discuss on the research team.

Part 2: Copyright unpacked with the DM Law Tool

Jo: Oh. For those of you who join us for the first time, or haven’t listened to the previous episode preceding this one, we’re here with Anna and Susanna, who work at the Competence Center for Digital Law in Switzerland, and have developed the DML tool. And in the previous episode, which I highly recommend for you to listen to, we talked about data protection, protection of personal data in your personal settings, as well as in a research context. And now we continue our conversation to look into copyright, what it is, what it means, what are national, international specifics. So, yeah. Welcome again, Susan and Anna.

Suzanna: Thank you. Jo.

Jo: Yeah, let’s dive right in with you.

Suzanna: So, first of all, certain generic details. First of all, what does copyright protect? It protects literal and artistic works. When three conditions are fulfilled, it has to be an intellectual creation. It means only what is created by a person can be protected by copyright. So, for example, machine content nowadays is not protected by copyright. We don’t recognize copyright protection to what is created by a machine if there is no active behavior behind the machine made by a person. A second condition is that the work must be perceptible by sensors. It means, if we can read a text, watch a movie, see an image, listen to music, that can be protected by copyright. Whereas an idea or the concept itself behind the text, for example, is not protected by copyright. Only the form of expression that the person gives to a certain idea is protected by copyright, not the idea itself. The third condition that must be fulfilled is originality, also sometimes called individuality, the character of individuality. And that’s the tricky condition, because it has to be evaluated again on a case by case basis. Because every time you are wondering if you are dealing with work protected by copyright, you need to wonder, is this work, is this form of expression original enough to be protected by copyright? Because if it’s not original enough, if, for example, a video is not original enough, I just film while I walk, without paying attention of lights or of a specific position or whatever, there is no originality, there is no personal contribution given by the author, then this video is not protected by copyright. And that means that anyone is allowed to use the video. I cannot claim copyright protection for this video. These three conditions are required internationally by all copyright laws of the world. There is an international act, which is called the Burn Convention, which is signed by almost all countries of the world. And the goal of this convention is to give it a harmonization of all copyright rules of different countries. Because in the digital world, there is no border anymore. We share content with so many countries. So many countries are involved in sharing contents. So it was needed to have one only international act that would apply to almost all cases. So the Burn Convention forces that these three conditions must be fulfilled for a work to be protected by copyright, then there are certain specific differences that can be set by national laws. For example, here in Switzerland, our Swiss law as well as German law, I know they grant copyright protection to photos lacking originality. So a photo made by a person is protected by copyright even if it is not original. That’s often the case of photos historically important for press photos that are done by many photographers from different media, from different press houses. And they have historical value because they are capturing an important moment, even if they are not original, because the photographer is not capturing a particular position or a particular light or photographers, maybe they are doing the same kind of photo. So there is a copper protection also in that case, that is an example to show that there may be different rules that apply in certain cases based on the country involved in a case. So when the author creates a word protected by copyright, first of all, the author is also the right holder. It means the right holder is the person or also an entity entitled to decide? How can this work be used by third parties, by anyone in the world? And only the right holder is entitled to decide. It is possible that the author transferred the rights to the right holder. This is the case very often when an author creates a work for the employee doing the job functions based on the contract, based on the employment contract, the author transfers all the copyrights to the employer or to the institution, not the person, but to the entity. In that case, the employer or the institution can be the university, can be a foundation, can be any kind of institution and authority is the right holder. And that means that this entity, the right holder is entitled to decide who can do what with the work. And if someone is willing to use the work, the person is required to ask permission from the right holder to be able to use the work for any purpose. Without permission, the person is not allowed to use the work. There are certain exceptions set by the law. Again, the Burn Convention foresees certain principles or wishes that are also in Europe. There are European directives which require countries to develop national laws that specifically explicitly set certain rules. So we have exceptions allowing anyone to use a word without needing to ask permission. But again, that can be different from country to country. So for example, all countries of the world have an exception to permission to use a work for private use, without needing to ask for permission. If I use, if I download a content from my personal use, I don’t need to ask permission every time I’m using the work for my private use. But then again, there is also an exception used a lot worldwide is the right to quotation but it’s not very wide, it’s not an unlimited right to quotation. I’m allowed to use someone else’s work to include in my work. For example, my thesis. In my research publication I’m allowed to include a part of someone else’s work in order to demonstrate. To better explain. To as a reference of what I’m explaining. Of what I’m trying to create but there are certain limits and these limits, this right to quotation can be different from country to country. Again, the principle is worldwide, the principle is the same all over the world and this Burn convention forces the same principle but then the details, the limits may be slightly different from country to country.

Jo: Sorry, I just wanted to clarify, to put an example from my experience, like when we want to cite a quote from a book, what might differ from country to country is the actual number of words.

Anna: Yes, exactly. Or when it’s for example,

Jo: Just a piece of the image or the whole image and would you then put a watermark, some sort

Anna: Exactly. That’s a very, very big controversy that is going on right now because like for example, we all have this right to quotation but then to what extent in Switzerland it is accepted by the doctrine and also by the federal court that a full image can be used as a quotation. But if we think of why there is the problem? The problem is again, as talked about privacy here the same there are several interests that are into play and that can sometimes be in conflict, one with the other. So on one side, copyright is part of the intellectual property rights which are included in the right to property, guaranteed by all our constitutions and also international Human Rights Acts. So the right of property gives a monopoly, gives a right of exclusivity to the right holder about the work, only the right holder is entitled to decide who can use the work. So for example, if for example, Getty Images, Keystone, they are right holders of the images they have and they sell these images. So if I use a full image, if I publish a full image, even if it is inside my publication, I’m still going against the interest of who is selling this full image. So it’s finding a solution, finding a fair balance between the right to property of the right holder and my order, the researcher’s interest in using the image, for example, or using any content. So it’s freedom of expression, freedom of research, also the right to inform and the right to be informed. There are many interests, many rights on one side that are in conflict with the right of property. So in Switzerland, as I said, the doctrine and the federal courts in certain cases not always, but again, depending on the circumstances of the concrete case, it is possible that a full image can be used as a full image can be used as quotation because it wouldn’t maybe in certain cases it wouldn’t make sense to only use a part of an image. How can I use only part of an image? That’s not the same in other countries. I know in Italy, in Germany, they absolutely don’t accept a full image to be quoted to be published as a quotation because this right of property, of the right holder prevails over freedom of expression and freedom of research, et cetera. So for a text it’s much easier because it’s easier to only extract only an excerpt of the text. So only the part of the text which is needed to quote to demonstrate what I’m talking about, I’m allowed to use this on this part of the text and there still is an interest in buying the full text if we think of an image that’s difficult. So this fair balance nowadays goes more into the side of guaranteeing the right to property instead of guaranteeing freedom of expression, unfortunately.

Jo: And then there’s also like now that we are in a podcast, there’s also the right to music, where again, from country to country what length of a musical can be used as an intro?

Anna: Again, it’s this fair balance between on one side music is part of freedom of expression. In Switzerland, our constitution, we have two different articles one is freedom of expression, a right to freedom of expression and another one specifically about freedom of arts. In other countries, freedom of arts goes into freedom of expression. So again, it is not possible to create new knowledge, new art, something new, without being inspired by previous works. It’s impossible. We are always inspired. Everything we create is based on a previous work. So it’s a very big problem if someone pretends to be very short, not even a very short part of your music can be included into a new work. So it’s a very big controversy. It’s very difficult to respect all interests or rights.

I don’t want to say that law is on the other side. It’s always asking permission to use the work from the right holder is a solution.

Jo: Think about it. It’s for people to be in touch, like one created, one put extra effort and tires and sold into a piece of creative creation.

Anna: Exactly. So even if the law says you’re not allowed to use the word without permission, it doesn’t mean that you are absolutely not allowed get in touch, ask for permission to the right holder and then hopefully the right holder or the collecting societies because there are every country has collecting societies who represent the interests of the authors and right holders. So then hopefully the right holder or the collecting society are willing to give or grant permission.

Jo: If you allow, I would like to draw the copyright discussion into something that’s crucial in the publishing process for researchers, like when it comes to the transfer of the copyrights as we publish. Which has become I think that originated as a necessity in the print era. Which we’ve I would say left in not all research disciplines and countries where research is conducted. But publishing is very much digital these days and then there’s claims that there is no need for copyright transfer anymore and still telling you because it’s convenient for the publishers and they can then decide how the data is being used and they can actually decide it back to us what happens on a daily basis which you might find morally questionable at least. But then also not so demonized publishers. All of them. And generally there’s also reasons even in the digital era for copyright considerations on the publisher side. So could you help us out here? So what are the conflicts? And why do we transfer copyright or do we even have to? And what are the publishers’ interests?

Anna: If we think of the development of publishing in the last years, we traditionally think of a publishing contract as the agreement between the author and the publisher, where the publisher is committed to editing and doing a lot of work in order to then sell oh, how cute. In order to then sell, for example, the book. There is really a lot of effort, a lot of work by the publisher until the end product that is then released, published and sold. Traditionally, this publishing agreement, publishing contract, it’s written about how many copies must be printed, where these copies must be sold, etc. Nowadays, in this digitized world, the publisher I don’t want to minimize the job of the publishers, but often it’s about granting a platform where the work can be published. But there is not this big effort anymore as it used to be. So that’s why it’s not anymore needed to transfer all the copyrights because the publisher is not part of all these creative, all this process of creating the work that at the end will be sold. So in such cases it is really possible for the author to retain copyrights and grant the rights to publish and to distribute and share the work through a license. So it’s not about transferring rights through account, transferring contract, it’s not about assigning copyrights, but it’s about licensing rights, granting the right to publish the work and the author remains the right holder, the publisher has the right to publish and then it depends on the circumstances. It still depends on the effort. Maybe if the publisher, apart from publishing the work, maybe there is also a certain amount of effort in advertising or really an effort in publishing and sharing the work. Maybe the publisher can claim an exclusive license for a certain period of time on the other side, if it’s only about really mere publishing the work on the platform and nothing else, of course there is no need to transfer the right, only even a non-exclusive license is enough. So dealing or agreeing on what? Copyright?

On one side there is the author, and on the other side there is the publisher and it’s about agreeing what are the rules, what is the role of the publisher, what is required from him to and based on that there are certain levels of copyrights that can be assigned or granted, et cetera. There are different possibilities of granting the rights. It’s not only about assigning or not assigning copyrights. So the researcher who is willing to publish must be aware of what are their rights, what are the possibilities? There is one possibility on one side is assigning copyrights to the publisher. That means the researcher, the author are no longer entitled to decide what to do with the work, or where to publish the work, only the publisher is entitled to decide about that. On the opposite side, there is a mere nonexclusive license which grants the publisher the right to publish. But then the author remains the right order and is allowed to publish the work also in other places and the author, the researcher, is still entitled to decide what to do with the work. The publisher has no right to decide about the work, has only the right to publish the work, and that’s it, nothing else. And within these two extremes, these two opposite possibilities, there is a wide range of possibilities and it’s really up to the parties. It’s called contractual autonomy. Parties are free to decide what to agree. So the researcher. Of course. The publisher needs to accept that both parties need to sign and accept agreement. But both parties are free to decide what to agree and there are really almost unlimited possibilities. Not only the two opposite.

Jo: But that’s what most researchers are not even aware of. That whatever they are being presented as a contract by the publisher to be considered for publication. Because there’s such high pressure to publish and then in certain journals. Many of which are powerful yes. But you’re saying and that’s also why many publishers are actually negotiable. So it’s definitely in the hands of the researchers to revise the contract and to add the contract to their needs and preferences and then go back.

Anna: But then if it is important also to understand that if the researcher wants to negotiate certain parts of the contract, then also the publisher on the other side needs to accept the changes. So it’s not enough to for example, the researcher receives the standard contract and is already ready to be signed, and the researcher by hand makes certain changes, signs and sends the changed contract back to the publisher and pretends that the publisher accepts these changes. No, it’s not always the case. It’s better to write a formal letter to the publisher asking for specific changes and receive the signature from the publisher that the publisher accepts these changes. It’s really about a mutual agreement, any change has to be mutually agreed.

Suzanna: Two things to add obviously this also depends on the ability of the publishers to actually want to negotiate. Now if they don’t want there is not much space for the researchers there, but at least we can give a try first of all and maybe a second issue might be beyond maybe not being aware that we can negotiate is also knowing how to negotiate and then really the time investment to also deal with this aspect. So if you think about how we publish now, it’s always a rush towards the end and then we have to finalize and we submit at the very end and usually these contracts are signed after first submission, but still then we have to do changes again. And so the focus is actually on the content and dealing also is the way of how something is then going to be published and this needs, I think from the side of the research quite a lot of effort and sometimes it’s just like OK, I’m interested in publishing now, I need a publication and at a certain point it just say okay, whatever. No, this whole way of publishing might need to change.

Jo: Also to find a space in the digital era and bring some of the regulations and policies that are still in place to modern standards. In essence, it’s really a trading agreement between the researcher and the publisher and what terms they agreed to trade under, where everybody has a stake and also the power to negotiate. And then it’s on both parties to either come to agreement or not. Simple as that.

Suzanna: Yeah, exactly. So researchers must be conscious of what are their rights but also able to negotiate with publishers, taking their time to do that, et cetera. And then Fair Principles are about suggesting OK, there is a goal of open access, there is a goal of open science releasing research content under an open license worldwide. But concretely, what does that mean? So Fair principles help concretely to share, to release data that are concretely open. Not only for example, if I release my work under an open license, but it is technically not possible to open it with free software, then it is legally open content, but it’s completely not open because it can only be opened with the same software which is under payment, etc. All so it’s not an open context. On one level there are copyright rules and then next step okay, now that I know I’m aware of copyright rules, how do I concrete apply these principles for my work to be open? Then the Fair principles. It has to be accessible also technically. Not only through a license. But also technically also for example. If we think we never think of language. But if I want to release my content openly but I release it in a language which is understandable only by a very small part of the world. Then it’s not really I mean someone is allowed to translate it because I permit any modification of the work but it’s not open content because it’s only understandable by those who know the language. All these concrete points of view must be considered in open science to say not only legal issues.

Jo: And then when it comes to fair, it’s also not only about human languages but also machine readability exactly to make it searchable by the indexing databases that we all now find that data that’s been published. I would like to now take the publishers or put on the publishers shoes what are negotiables and non negotiables from a publisher perspective? What do they need in legal holding of our research, manuscript and data to actually still be able to process for publishing?

Suzanna: You should ask a publisher well, again, basically, first of all the publisher needs to have access to receive the work in order to be able to publish it, the main requirement but then it depends on the circumstances, unfortunately. Sorry, it depends on the agreement, it depends on what is the role of the publisher. In that specific case.

Jo: Like you said before. It was the publishers duty to format and they still do the layout to some extent but the formating has been pushed by the publishers towards the researchers and now researchers found themselves not only having to do the research. But also preparing the manuscripts, yes. Writing the text. But also formatting the text so that the publisher has as little work as possible with it but we’re still paying for whatever amounts in article processing charges and you might ask what justifies certain amounts that we pay and expect to pay. But there’s another discussion that’s price pricing and that’s another discussion to have not so much legally.

Anna: Exactly it depends on the role. The effort of the publisher in certain cases. Of course. If the publisher is the one entitled to format. To edit. To do the layout. It’s one thing if on the other side. The publisher only gives the possibility to publish the work on a platform so it guarantees a certain visibility. But nothing else. No editing then the law doesn’t set a specific amount of rights that must be transferred to the publisher. It’s really free for the parties to negotiate, to agree, depending on the circumstances, depending on one side recognizing what is the role of the publisher but nothing must be granted to the publisher apart from of course sending the work itself so that the publisher can either edit it and publish it or only publish it.

Jo: Researchers could also design their own contracts and say here’s our work, here’s our tax, here’s our data, we already license it with CC by attribution only and we now hand over to you we might also pay fee for you to publish this on our behalf online in your journal and keep all the copyright and all the legal data aspects to the researcher’s.

Suzanna: Yes. So in that case the publisher only publishes the work, nothing else. In that case it’s a license. Of course, if the publisher agrees. But it would be enough to only enter into an agreement as a license to publish the work and that’s it for your researchers to remain right holders. The publisher only has a right to publish the work, then it either can be an exclusive license or non exclusive. It means the publisher is the only one who has the right to publish. Right holders are not allowed to publish the work elsewhere or if it’s a non exclusive license, then you are also allowed to publish the work anywhere else that’s possible to agree with the publisher. The publisher of course must accept.

Jo: Yeah, this one is probably also good to refer to the Chef or Romeo database, which specifies most publishers in the western ecosystem are listed here. Also non western journals to some extent. And we also put that link into the show notes and blog post where you can search by publisher what their legal requirements are, how they handle copyrights, at what stage the processing of your manuscript, meaning the handle and manuscripts, the author’s version, the promised version, the peer reviewed version, the layout version, version of records and then the published version. So each step is the publisher where the publisher basically holds the not ownership but holds the manuscript in their hands and processes them, where they add value to the manuscript. And therefore then is it that then they actually get copyright to the work because they’re processing it with our agreement?

Anna: It depends on the agreement the publisher has with the author. It’s not something automatically there is no rule such as if your effort is more than a certain percent of the work, then automatically you become the right holder. No, it depends on a case by case basis and maybe if the publisher has a certain amount of work in creating the entire work, it is possible that the publisher is joint author, co author with the writers. So it depends on the case. Our Swiss law there is one article that says it can be the case. When the publisher decides about, for example, about the topic of the work, about the book, the publisher invites or asks specific writers to give their contribution into the work. Each contributor writes, for example, one chapter and then the publisher again himself, he gives the structure to the book, decides what chapter goes one after the other and the publisher decides what are the topics that must be written about. So in that case, the writers don’t have a lot of room to decide about the work, to say they only write the text, but they follow the instructions given by the publisher. In such a case, of course the publisher is the right holder. But it can be certain cases again, depending on the work behind it, it can be a joint author with writers. If the writers only really execute the instructions of the publisher. It’s possible that the publisher is a right holder and writers are not even authors. So it depends really on this. There is a wide range of possibilities depending on how much each one had a role in creating the work. But this is an extreme case where the publisher is the one who directs the whole work, decides what must be written, how to structure the book, the chapters, who will be the writer, the publisher decides who are the contributors, etcetera. Etcetera. If it’s not that extreme case, in all other cases it depends on the role of the publisher and authors are allowed to negotiate because the publisher is only about really a mere publishing of the work, then no need to transfer copyrights.

Jo: Thank you. I would like to maybe conclude on the copyright chapter before we come to look into the Jim again with the conference support. And also I like just to mention that we will take this up in future episodes of this show because also, again, it is a tough thing to do. It is to my heart to consider ethical and moral aspects and ownership aspects of copyright in a research context. And again, this was also developed by indigenous representatives who saw potential infringement of their knowledge by research practices. And the insufficiency of our understanding of the copyrights will always be tied to one individual person. Whereas indigenous and I think all over the world, like societies, well, in indigenous communities in particular, there’s no such thing as individual ownership when it comes to especially traditional knowledge. It’s always a collective ownership of the community. But we don’t have a legal system in the research context. There is to justify that and to ensure that knowledge is protected towards what we would do under the copyright for the whole community. And therefore they added these care principles like authority and control, responsibility, like who is responsible for the curation management of the data and ethical aspects in all directions when it comes to data protection. So the legal system that we established for western societies is very much morally driven, isn’t it? So it tried to establish structures to rely on, to protect individual interests, to protect societal interests, to ensure that we don’t harm each other. So it is actually comparable, it’s just that it has limitations because it’s based on a capitalist or modern society, whatever that means concepts.

Suzanna: Yeah, you need to consider that law must apply to all cases. So it’s law must be abstract and general in order to be able to apply to all cases. Sometimes it seems like law is very far away from a concrete case or from certain circumstances, from a certain specific context. So nowadays we use more and more agreements which are more quickly to create, because law requires a lot of time to be changed, a lot of time to be in line with the development. Of the society. Whereas these conventions or agreements or these principles, they are closer to a concrete case, to a specific context. So we try to create this either we can call them like agreements or principles or conventions. They can have several names. But the goal of the aim of these acts. Of these, how to say principles. Is to find a solution that is understandable. That is accepted worldwide. Or that is accepted from a whole society and that is applied by a whole society where the law has difficulties in being in line with that specific context.

Jo: Basically trying to put a general concept which covers any potential case without being specific. But the policies and agreements are law specifics to regulate what’s not more. Yes, excellent.