Ludmilla Figueiredo is a research data and code curator coming from a background in ecology and conservational biodiversity. In the first episode (part 1), she talks with Jo about the implementation of the open science principles within the fast-paced and heavy workload researchers must handle.

In the second episode (part 2), Ludmilla presents to you a simple yet effective computational workbook she developed with her colleagues, to make FAIR data sharing easy for anyone.

Bridging Academic landscapes.

At Access 2 Perspectives, we provide novel insights into the communication and management of Research. Our goal is to equip researchers with the skills and enthusiasm they need to pursue a successful and joyful career.

This podcast brings to you insights and conversations around the topics of Scholarly Reading, Writing and Publishing, Career Development inside and outside Academia, Research Project Management, Research Integrity, and Open Science.

Learn more about our work at https://access2perspectives.org

Ludmilla Figueiredo is a research data and code curator coming from a background in ecology and conservational biodiversity. In this episode, she talks with Jo about the benefits that coding has in open science.

Ludmilla Figueiredo has completed a postdoc studying the payment of extinction debts at the Ecosystem modeling group of the University of Würzburg in Germany, and, since March 2022, works as a data and code curator at the Data and Code Unit of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig. Among her duties, she has to support researchers in the application of Open Science and FAIR principles, sourcing from her participation in the “Freies Wissen”Open Science Fellows program (2020/2021, Wikimedia Deutschland).

More details at access2perspectives.org/2022/11/a-conversation-with-ludmilla-figueiredo/

Host:Dr Jo Havemann, ORCID iD0000-0002-6157-1494

Editing:Ebuka Ezeike

Music:Alex Lustig, produced byKitty Kat

License:Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

At Access 2 Perspectives, we guide you in your complete research workflow toward state-of-the-art research practices and in full compliance with funding and publishing requirements. Leverage your research projects to higher efficiency and increased collaboration opportunities while fostering your explorative spirit and joy.

Website: access2perspectives.org

[To see all podcast episodes go to access2perspectives.org/conversations/]

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8217-7800

Website: ludmillafigueiredo.github.com

Twitter: @ludmillafi

Instagram: /ludmillafi/

Linkedin: /in/ludmillafi/

Github: ludmillafigueiredo

Ludmilla’s Open Science Fellows project: github.com/FellowsFreiesWissen/computational_notebooks/

Credit: Gerhard Bayer, Bayer Fotographie 2020

Ludmilla Figueiredo has completed a postdoc studying the payment of extinction debts at the Ecosystem modeling group of the University of Würzburg in Germany, and, since March 2022, works as a data and code curator at the Data and Code Unit of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig. Among her duties, she has to support researchers in the application of Open Science and FAIR principles, sourcing from her participation in the “Freies Wissen” Open Science Fellows program (2020/2021, Wikimedia Deutschland).

Which researcher – dead or alive – do you find inspiring? – Prof. José Eugênio Cortes Figueira, Population Ecology lab, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais

What is your favorite animal and why? – Whales, especially humpback whales, because they are big and beautiful.

Name your (current) favorite song and interpret/group. I Can See Four Miles by KT Tunstall

What is your favorite dish/meal? – Rice and beans (from Brasil)

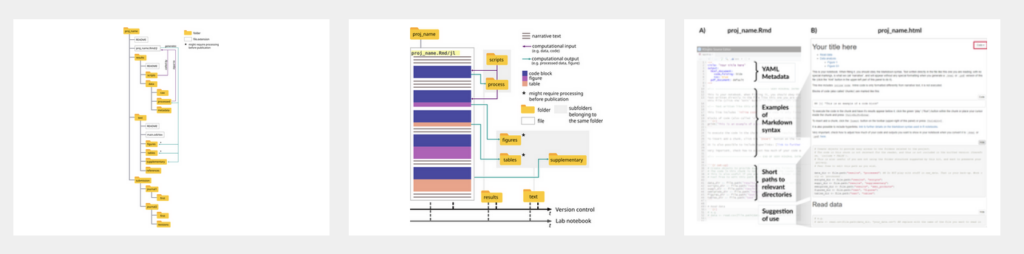

Computational Notebook (toolkit)

References

Figueiredo L, Scherer C, Cabral JS (2022) A simple kit to use computational notebooks for more openness, reproducibility, and productivity in research. PLoS Comput Biol 18(9): e1010356. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010356

Figueiredo, L., Krauss, J., Steffan-Dewenter, I. & Cabral, J. S. (2019). Understanding extinction debts: spatio–temporal scales, mechanisms and a roadmap for future research. Ecography 42, 1973– 1990.

Würzburg University press release (2019): Prize for Ludmilla Figueiredo. When ecosystems are disrupted, it can set species extinction in motion. For her research in this field, biologist Ludmilla Figueiredo receives a prize from the journal Ecography. https://www.uni-wuerzburg.de/aktuelles/pressemitteilungen/single/news/preis-fuer-ludmilla-figueiredo-1/ (german)

TRANSCRIPTS

Part 1: Implementing the FAIR principles for the curation of Integrative Biodiversity Research data

- Go to Part 2: Computational notebooks for more openness, reproducibility, and productivity in research

Jo: Welcome. You’re listening to Access 2 Perspectives Conversation. Today with me here in the Zoom Room is Ludmilla Figueiredo. We met a couple of years ago through the Open Science Fellowship program by Wikimedia, Germany, where I had the pleasure of working with you, Ludmilla. And I’m very glad you’re joining us today for this podcast. Welcome very much. Ludmilla: Thanks for having me, Jo. It’s a pleasure.

Jo: So for the preparation, also like you’ve done a lot of work. We’ve worked together in open science and open science realm, where during the Wikimedia fellowship you worked on a project developing an electronic lab notebook that’s really simple to use or simple in structure for easy adaptability. We’ll come to talk about that. You have a background in ecosystem conservation, broadly.

Ludmilla: Yeah, broadly. More ecological modeling and ecological theory. Yes. With bills to conservation.

Jo: Basically, your research informs ecosystem conservation. Can we say that?

Ludmilla: You could say yes, because I used to work with extinction. So what I do is to try and understand when and how they go extinct. But to be fair, I have actually changed jobs recently and become much more involved with open science practices and helping researchers. So it’s really fitting to my Wikimedia project, which is great. And also funny how fitting it is.

Jo: Great. Yeah. It’s funny to see how careers sometimes unfold just through fellowship or project opportunities that you’re there to tap into, and then a whole new career path opens up afterwards. So would you guide us through some of your career steps and the turning points or what your research interest is from your undergraduate studies and what led you then to ecosystem modeling towards open science and open science practices and what you’re now working on?

Ludmilla: Sure. So I’ve always wanted to study biology. I was always concerned about environmental questions and conservation and so on and these type of issues that we have, since I was a kid, to be honest. So studying biology was pretty much a no brainer for me. I had decided much before we had to make a choice. And in my biology undergrad studies, I specialized in ecology. But honestly, I always found ecology a bit hard because sometimes it can be presented very case by case until I was introduced to ecological models which basically summarized the big ideas and showed you the main I mean, it’s a model for a reason, right. They summarize the main processes, the main patterns that we can see. So this is what got me completely hooked on ecological modeling. And also I liked a bit of mathematics, so it made it easier for me. So from then on, during my undergraduate, I had an exchange program from the University where you could get a scholarship to go study abroad. And through this I went to France. And also by chance, I always said I’m sometimes very lucky that they were just starting a master’s degree there in ecological modeling for a specialized master’s degree. And because of the way Brazilian and the French curriculum works, I was able to start this master’s program and then I finished it up. So I had a master’s in ecological modeling, very specialized in. This was seven years ago and the use of models was like a big thing in ecology. It has always been important, but there has been a significant rise in the last ten years or so. So after the masters, I was looking for PhD projects and I found this one in Wurzburg. It was about ecosystem debts, sorry extinction debts, which is extinction that happened late after some disturbances. So you can think of some forests being cut down for either some construction work or for wood or something like that. And then what often happens is that the species, the birds and the mammals or even the plants, they’re not immediately affected. Okay, you have some that die, but the whole species or the whole population that lives in that area and around that area is going to suffer for many years before it eventually comes extinct, or in some cases not. But it does delay the fact that you can have and because it can last several, dozens of years. The idea of the project was to build a model to simulate it. And this is where my interest in documenting my work started to be. It was not only about me wanting to do it was more that I realized I have to do it. Because when you build such models, you have to combine what you know from theory, what you know from observation. You take pieces from different parts. And this means that you have to say, okay, this is coming from this. And this is why I think, for example, if I’m trying to simulate how plants reproduce and live through their life cycle or something, I have to justify how I think, how many seeds they produce per year, how much they will grow, and so on. And with the model that we were building, it was quite complex. So we wanted to simulate a lot of mythological dynamics. We would say, so this means competition between species, reproduction, growth and so on. So you have to justify it. Because when people read it, either reviewers or my peers, they have to know, okay, I’m not just doing this because I want this to work, I want this to simulate something. I need to show that it’s justified by theory, by previous observations, right? So this started mostly as something for me and it was very much focused on documentation. But honestly, it was also a way for me to combat a bit of imposter syndrome because I was like, okay, I’m not completely sure what I’m doing here sometimes and if it’s wrong or not. And I just realized, okay, if I write it down and I give it to people, to my supervisors, to reviewers, they’ll be able to see if there’s something wrong. And then they’ll tell me and then there’s not this fear anymore, right? I’ll just know what is wrong. And also at the time I worked for the zoology Department at the University of Wurzburg, but also at the Center for Computational and Theoretical Biology. And there is a very much like a very computationally savvy crowd, which I was not at all in the beginning. And I was coming across all the software development tools and practices and they have a lot going for the documentation and the project management part. And I was trying to combine this because some of them were very useful to keep track of your work and so on. And I just started to incorporate some practices into my own project management that I did for myself and at some point actually discussed with them because they’re always promoting the seminars where we talk about how to make our work better or how to work some new tools that make our life easier. I realized that I actually had quite a good system. I was actively trying to improve it. And so I presented the idea to them and I saw that it was something that they were interested in. And then I kept developing it. And then at some point from the University of Wurzburg graduate school, I saw the announcement for the Wikimedia project and this was the idea, right? Okay, we’ll find you so you can work on a project that fosters some aspects of open science. And I thought that maybe because I was at the end of my PhD and I wasn’t sure where I would get funding further. So, okay, this sounds like a good way of assigning some hours to wrap up my ideas around this project and make it something that others can use instead of just a tool that I myself use. And I have to maybe sit down with someone for 2 hours to explain it to them. This is how it came to be. And through the project, I learned how much open science practices make sense. Like the saying goes, open science is just science done right. And I learned about other aspects of open sense that were quite important for me because I thought that I was getting very cornered into this very academic side of our work, which is producing research for our peers. My world was closing in a bit. The open science movement opened up my eyes for these other ways that we can make our search a bit more approachable. Maybe not directly as science communication, but just for people a little bit outside of our field because this is something that happens as well. In ecological modeling, I would often sit down with my more empirical colleagues and they would be like, I don’t understand anything you say and this is not good. It doesn’t mean that what we do is super hard. It just means that we’re not communicating well. So this was the stuff that started to become more and more obvious for me. And again, I would see this documentation practice as a way of bridging these two areas, the empirical and the modeling side of it. So I was working. I kept this practice for myself. I worked on the project during our mentoring and wrote a paper on it. It’s on the review. It should come out soon. And actually by chance, again, six months ago or so, I saw this announcement for work as a data and code curator at the German Center for Integrative Biodiversity Research, here in Leipzig. It’s an institution that accommodates efforts from Halajana and Leipzig, and it fits perfectly honestly with my interests, the kind of work that I think I’m good at. So as much as I love the research, I honestly think I’m good at this part of the curation and sitting down with the researchers and explaining why this is important and showing how to do it. And I mean, with the work that I did at Wikimedia, this was this part of explaining it to people and making it easier for them. Also, I got to work on it as I presented my ideas to other people and discussed it with colleagues. I applied and got the job. I started two months ago, and I’m still learning a little bit in the workings of ideas and so on. But what I’m really happy about this position is that they have this dedicated position to support the researchers, because this was also an idea that became clear in my project and it can feel like asking people to do more work, which is already for a researcher is a lot, especially younger researchers who are the ones who are going to have to do these practices for going to have to have data management plans for the grants. It can feel like a lot more work, especially if you’re not so knowledgeable in the digital documentation parts and you still have to establish your workflow, which was what I did during my PhD. But I mean, I had the time to do it, but it became important to me to show, okay, it is a little bit more work initially, but it pays off eventually because one, you get the documentation that you will need to publish something good. And also it’s actually something that came across in the reviewers process for our paper is that it saves time for the researchers themselves. When they go back into some work, they are able to catch up much easier or if they have to pass it on to some colleague that is taking over the project, someone new is coming. It’s much easier to pass it on if you can just, okay, read this and then we go through your questions or rather, okay, let’s schedule a meeting, and then I have to go through all of this with you. You have to write it yourself. So I’m really happy with the combination of things that got me here and that I’m always excited to work on it when I see that I’ll get to do it as a job.

Jo: That’s great to hear. So you focus on conservation biology and you support researchers who have a research focus on that discipline or research topic in particular.

Ludmilla: So not so much conservation biology. The idea is very open for biodiversity research. So we have the conservation groups, we have the people working on biodiversity and economics. We have the people working on biological interactions, which would be something you could say like blue sky research, more or less always with the idea of how we can use it for conservation. But not only this idea of having integrated is this that you allow work groups to work on their own research areas and then the integrative parts come and then they can apply it to conservation or to science, communication or to human wellbeing, and my work actually is really on supporting all of them, all of these groups. So I don’t do research anymore, except for finishing up papers that I still have being reviewed or finalized. My work is really concentrated on whenever they have data that they want to publish. So the iDiv has its own data portal where the workers and the PhD students are asked to publish their data in their code as well. They come to us and they say, okay, I know what I’m doing, I just want to publish. So I’ll just do a basic duration job. I’ll just see, okay, it conforms to our standards, this and that is more or less understandable.

And then I just need to say, okay, check. I give them a DOI and they can go about their lives, but it can also be the case that they come with us. So, okay, I have no idea what is happening. Please help me document this code or please, I need to publish this. The journal asked for it. What should I do? And we support them along the way. And also eventually we start giving a bit more courses and workshops with this idea of open science practices and good scientific practices for the PhDs and even the more senior researchers. So it’s really dedicated work.

Jo: That’s super interesting that you’re able to work on intersection between the different research topics or processing around biodiversity. Some explorative like basic research, trying to understand ecosystems of different kinds, some more applied research or conservation oriented, and then how it all fits into a bigger picture of understanding ecosystems. Is there a regional focus on Germany, on any particular ecosystems, region wise?

Ludmilla: It’s very international. So they have projects that are specific to Germany. So some sit and science projects. I’m even participating. I have a B hotel here on my balcony where I’m sampling some bees for them. But there are all kinds of projects. They have ecological stations in other cities and they have cooperation with other countries. So it really depends on the group and on the interest.

Jo: Do you also help them with FAIR principles? That is, how to make their research FAIR.

Ludmilla: Go on.

Jo: I’m asking because we had a recent episode on this podcast with Donny Winston where we also talked a lot about FAIR principles and how it sounds so easy and nice. And yes, let’s all do it in theory, but when it comes to doing it, it becomes a problem. How is it actually being done and where are the examples that we can take as an example to organize our own research data? And then I tend to say, well, sorry, but it’s normally quite not even discipline, but also research topics specific. So every research project needs its own data management plan and every data point, every metadata point needs its own assessment for how it can be FAIR. But then, of course, also the FAIR principles give some general guidelines. So that’s one question. So how is it in your day to day life? Like how do you manage to inform researchers from all these different disciplines within biodiversity, the broader topic, but still each of the research groups working on very distinct and specific research topics. What’s the common denominator? Is there a pattern that you discovered? Well, it’s only two months into working there. But how easy or difficult is it helping them and implementing the FAIR principles?

Ludmilla: I’m actually hired by the University of Vienna, so by the Fusion group at the Informatics Department led by Professor Bijeta Conqueris. And are they working on building the structure to allow the application of FAIR principles for a long time. So I’m getting on a very well established structure to support us. So we have constant meetings, we have constant interchange of knowledge. So with that in mind, I would say I have a solid structure from where to work and in terms of applying it, I also have to acknowledge the work that was done by my colleague, the data stewards at iDiv, Dr. Anahita Kazam. She has been working for a year and a half in this new data code unit. So they have restructured this dedicated data code unit again to support the publication and documentation of code at the iDiv. And then the work that she has been doing has been mostly on a lot of training. So simply quote unquote workshops to inform the research about the importance of the FAIR principles, what they are. And I would say even more specifically, I would say that the work that we do with the developers of the Fusion group, so the group at Vienna where they are working on making our databases more accessible, I would say mostly and interoperable with other databases out there. So our job from a sense is to say okay, what are the databases we need to communicate on? What are the bigger, for example, repository platforms that we need to be findable at something like this and get this to the developers and also go to the researchers and say, okay, we really need this feud because let’s say a user comes through the portal and wants to search for this or that, this or that type of data. We need them to find that; they might not know your research in detail. They might come with a blank mind and not know exactly what to look for. So in summary, I would say this is how we do it. We have a very solid base for matters to work, and then we work more on training, especially the young researchers. But also justifying very well showing how important it is, how this pays off in the end to have this work available and FAIR and how it reflects and the advancement of science and the advancement of knowledge and cooperation. And ultimately, if they want to be very selfish, quote, unquote in funding, even if you don’t convince them by the FAIR of it, you convince them by funding.

Jo: So maybe we should also mention this for the listeners who are not familiar with the FAIR principles just to explain the acronym F.A.I.R stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and reusable for data items to be, which is not to be confused necessarily with Open. It can be that FAIR data is open, but it doesn’t have to be. And this is a common misconception when it comes to conservation biology and biodiversity, or in particular with the research groups that you’re working with. Is there data that should not be publicly available, like sensitive data that some research groups work with? And what would that be?

Ludmilla: Yes, you can have data from camera traps, which are basically small cameras that you put in the middle of a forest somewhere, and they activate by movement, and then they keep capturing the animal that is coming through. For example, you would say, okay, I did this study in a forest, Madagascar. I had 20 camera traps set up, but I’m not going to review their location because it’s sensitive, because if one of these camera traps captures some very rare species of Lemur or some other mammal that is endangered, you don’t want to be revealing their locations and helping few people find it. So this would be the type of sensitive information that we don’t need to make public. And it doesn’t affect the end result of the work. If people want to reuse it, they will be able to. They don’t need to. And they can always ask the co authors if they absolutely need it. And then there is an agreement and so on. So the work is still accessible. It’s still findable and it’s still reusable. It’s just that there is this small detail that we have to work on, and this is the type of work that we do in curation. Where they say, okay, I cannot show this. We are okay, all right. We just informed this in the documentation. Make it clear and so on. So this is totally possible and this can definitely happen.

Jo: So it’s basically to protect animals and plant species from illegal hunting.

Ludmilla: Yeah. Or even curious people. For some reason, tourism really wants to see that species, though. We know that they’re in a very small patch of forests. No, we don’t want to and it’s a nice thing for the researchers to know that they can still make their data available for others without endangering their object of study, because especially in these cases, the animals, it’s almost like a hard thing. It’s a love thing. So the research is very precious about space and we want to protect it as well.

Jo: Yeah, there’s the registrydata.org, the registry of research data repositories. Are your data repositories linked there already or not yet? Or for a reason, maybe not.

Ludmilla: That’s a good question. I think it should be.

Jo: I’m just asking because in some cases, I assume there’s also reasons for keeping certain data sets separate, for organizational, political, whatever reason, the registry data is an attempt to centralize data. Like the central registry with global research data repositories represented.

Yeah. And it’s work in progress. So that’s basically just for the listeners. Maybe also a source to check out. If you’re working with research data or interested in expiring research data, you can search this registry by discipline, research topic, region, and then you find research data press, also region, research topic.

Ludmilla: So this is something we do at iDiv data portal. We have different data sets, right? And the data set can be made open or not, depending on, for example, the researcher wants to do an embargo until they want to finish publishing, analyzing everything they want to do. So it might be the case that some of our data is not available yet, but we keep an eye out for it. Okay. Why is it embargoed? We want an extension or something. And so this might be the case where it won’t be open and it’s made case by case. So this is also part of the curation job where the researcher says, okay, I don’t want to publish yet, I want to document it and deposit it, but don’t make it open yet, please. And then we take care of it. Yes.

Jo: That’s also an important aspect because some open science enthusiasts call for us all to be as open as we can be. But then there’s also a level of responsibility and accountability. And cleaning up the data set is a lot of work. It takes quite a bit of time. So as much as we want to be open about sharing data and research results, there’s also this responsibility component where we need to make sure that the results that we publish to researchers is actually FAIR not only for the data, but also to be interpreted by the researchers and contextualized properly, just to have a shout out. Also for understanding why some research project might take some time to perform their results or make them openly accessible and searchable online. But the idea with FAIR, is to be fair also for our own sake. Like many PhD students, including myself, know very well what it means to find yourself towards the end of your PhD, having to write up your thesis and then going through your lab notebook. Which brings us to another topic. And I think this is what electronic lab notebooks can help us tremendously in avoiding the stress and the despair that some of us have experienced throughout the PhD and especially towards the end. But from the start of your PhD or any research project really to have a system that makes it easy to capture your results, to document contextualize on the goal, and then to have easy access through digital workflows towards the end of the PhD or towards the end of a research project when you want to write it up, publish the data set along with the manuscript. So what was it that brought you to conceptualize the project that you presented at the Wikimedia Open Science Fellowship program to build an electronic lab notebook? Why? I think you mentioned in the beginning to our conversation here that you found a need based on your personal experience for that, just explore a little bit more.

Ludmilla: I think it was a combination. So from the very beginning I had a lot to make sense of because the idea behind this ecological model, especially if they are big and complex, is that you’re going to combine different ideas from different theories in different areas. So I had to organize my thinking around this and this meant reading loads of articles and making notes and learning German in the evenings. So if I left something for two weeks when I came back to it, it would be really hard to get back in or I would read something and have no idea where I read it. I just remember a term or a word and then I would be able to, for example, search for it somewhere in my computer. So it was a mix of okay, I need to have a place where I can put my thoughts down and I need to be able to search through them very easily. So I would say that those are the main motivators, which is why I switched from written notes, which was what I had. And I still have two full stocks of paper on it to an electronic system and I still use it to this day. And I use a much more complicated system that they actually want to present and I kept working on it. So with this idea of okay, I need to write down my thoughts, I need to be able to search through them. And as I would have meetings with my supervisors, this is where they need to be able to communicate it and to justify myself to start to be stronger. This also would mean that I would have to go back to documentation and show. Okay, I got this paper and this was my reasoning around it, because it’s not only the reference. You have to be able to explain it. And to be honest, my memory is not that great. So sometimes I simply forget things. So to have descriptive and well written notes is very important in that sense. And finally I was getting so caught up in this system that I actually had a very complicated system. So it got very complicated. And that was a lot of work. I mean, as boring as it sounds, I liked doing it for some reason, but at the same time, it was eating my time. So I went back into trying to simplify it. And this is where the discussions with people at the CCTB in Wurzburg, the Center for Computational and Theoretical Biology, this is where it became important to me to show them, okay, this is what I’m doing. Are you guys doing something different? Are there any steps I could cut and discuss with my colleagues also in the ecosystem modeling group there, because we were all interested in it. So you can think of a bunch of nerds talking about tools so we can get far. Like you said, it’s doing a proper job, doing a good job of communicating our work. Which again, as I said before, in ecological modeling, it’s very important to come across to show that it’s not just a bunch of equations that we put together. You can actually understand it. And it’s important because if you think that we are talking about extinctions, it is going to eventually affect conservation species. It has the potential to affect policy, so we have to be able to justify it for our peers. So in the immediate effects, I would say, but also for stakeholders and whoever is involved in transporting it into action. And this is where the good documentation makes it easier. Okay. Someone might not read the menu of our model, but it can be translated in a more simplified language. And for that, you need good documentation. You need to show that it’s based on reality. It’s not like coming out of my mind and creating a fantasy world.

You could think of these three main phases of okay, I need something that is searchable and can retain my thoughts. Then I need something that my supervisors can understand. And then I needed to make it simpler so that I could do it properly and not waste so much time on it. And through this whole time I had the support, as I said from my colleagues, this is to shout out to Juliano, Juliano Samuel, my supervisor, one of my supervisors at that time, who always encouraged this type of exploration and allowed us to discuss it so much. And this is what was a refinement. And by the time I came to the Wikimedia project. I also got very nice reviews from my application, which was the main point that I was kind of aware of, but I wasn’t sure how to do it. Okay, there are quite a few resources online already if you look for how to organize your work in R, which is a soft programming language most ecologists or biologists use. You will find different posts online, different videos. And this was something that was said, okay, this work needs to show how it’s going to be different from all these others that exist. And this is where it also contributed to this idea of mine to make it very simple. Because from these tutorials, I would often see that they require the researchers to have some background in either computational science or be quite digital or computationally savvy and it’s not always the case. And as I said, I don’t want to add too much work to people’s workload already. So this is the part that probably took the most time for me, that is, organizing the work and not only the workflow that I proposed or the way that I propose people do it, but also the language and even the figures or the type of tools that I use to make it very simple for someone to catch up and start using it very fast and not have to do a lot of maintenance work, which was what I said before yet for it to be effective. Because I have something simple, but it doesn’t quite get there. This is not what I was going for. So finding this balance took me some time, but in the end, I’m quite happy with the results. So, yeah, if I had to summarize it would be like, okay, let’s get the very minimum that you need to know yourself, what you’re doing, tell others what you’re doing, and don’t waste too much time producing it, I would say.

Jo: And then also reproducing it. When you try to understand your structured form, you can track your own research documentation more easily. So you summarized the project; Is it available on GitHub?

Ludmilla: Yes.

Jo: And you also summarized it in a manuscript and published it as a preprint?

Ludmilla: Yea. But it’s coming soon because I haven’t found a preprint that takes tools and such types of papers. It’s not new research. So the preprint service that I tried to put it on, they were like, yeah, we would like to have new research available.

Jo: Really? That’s discouraging to hear because normally preprint services are meant to not have bottlenecks of that sort. You could register it on Zenodo and put it there. Zenodo doesn’t have any constraints.

Ludmilla: Yes, I can try, because this was the preprint service that I looked into, but it might be the case that I put it on Zenodo as you said, I think it’s on a good track to be published soon. And in any case, the GitHub page has everything, quite a good summary, I would say. And this was also something that became important was that I have video tutorials that walk you through the work because some stuff is easier shown, then I can talk about it as much as I want. If you don’t see it getting done, it might be a bit hard to imagine how it works. So the video tutorials I think are good and are one of the main resources that I have in there.

Jo: Yeah. I have to admit, I haven’t followed up since you published those. Maybe since it’s open, you can also put it on the Access 2 Perspectives website as a resource and just have the dissemination. Have you heard of people adopting your research?

Ludmilla: So I presented this to the people at the Center for Computational and Theoretical Biology, CCTB. And actually I heard from some people that they are using it. I also found some links to it in some FAIR Points organizations. So the event series that they have. The other day, I was just going through the material, and my stuff is in there. So that was nice. Whenever I talk to people, they always say, please let me check it because I think I was searching. I also had people from the three departments telling me, okay, this sounds doable. I can use it because this was something that I made sure to go, okay, let’s get the more empirical crowd to test it and see if they would actually adopt it. And I think it has a good track.

Jo: Nice. And is it targeted as Biosciences or can it be adopted by any discipline potentially? What are those limited or specified for buyers?

Ludmilla: Not really. I think as long this is actually something also that came into the review process. And I was happy that the reviewer said, I don’t know why I initially targeted ecological research, because this is the example that I have. But what they said was like, I don’t know why you are targeting it. I think many people would benefit from it. So I would say that as long as you have some part of your work that is documented. But if you have computational work that you need to write down as a script form and that you have results that you can show and preferably data that you can store somewhere you can use it. So it’s very generic, as I said, the examples that I give because in the repository you see that I have some examples of, okay, what would the final product look like? I use examples from ecology. But as long as you have some work that has a part of computational work that you need to explain or thinking that you could use it, because the basic idea is having this document where you have the narrative text where you explain your reasoning, you have the code where you actually apply it, so to say. And then you have some graphs if it makes sense, where you show the results of your computational work and also some discussion in there if it makes sense. So in this sense, as long as this is the case for your work, I would say it’s useful. It’s transferable.

Jo: Yeah. Great. I remember our conceptualization discussions and how you present it. It’s not exciting and highly useful since the beginning, and it’s really great to hear how it’s not being adopted and used by an increasing number of researchers. I’ll do my part, and maybe also through this podcast, some more people will be able to find it. So we will put the link to your GitHub repository describing it into the blog post.

Yeah. So for some concluding remarks, thanks for sharing with us your journey through conservation biology, biodiversity, data analysis, research, modeling etc.

It’s quite a journey, and it’s captivating how passionate you are about each step in that journey and how it’s still on each of the topics and everything will make a lot of sense on how you position yourself also with your career. What would be your recommendation to the listeners from your experience when they hear about open science, when they hear about data management or open data fair data, is there something from the experience of your consultation and the support you give to the researchers at the Institute? What are the major challenges, and how would you encourage people to overcome this and to dig in?

Ludmilla: I would say something that I heard a couple of times already was I’m afraid to publish my code and see what people will do, which is something that comes around, but I got to hear it personally. So don’t be afraid of it. The community is usually very open to share and improve if there is something that urgently needs fixing. So people are usually friendly about it, I would say. So don’t be afraid to publish your code. To have people talk about it. It doesn’t need to be perfect. It is good if you explain yourself, but starting slow would be the second. So the first one, don’t be afraid. Put it out there. The second one is, as I said, starting slow. Don’t try to go with the most pristine routine. It might take some adjustments, but it’s better to get it done than not to do it at all, which was also something that I did. It took me some years to refine my process, but I eventually found it. And hopefully the work that I put out helps some people along this way.

Finally, this fear has been decreasing, especially because there has been a lot of communication about the fact that getting a data citation, getting a data that you produced cited is also being recognized more and more. So it doesn’t mean that your work is going to get robbed or that you’re missing opportunities. You have the flexibility of saying, okay, this is some work that I really want to do myself. So I will hold on to this data for some time. But eventually put it out there so that others can use it because you will get the recognition for it. And in a bigger sense, in a more altruistic sense, I guess, you would be contributing to science in general. And if you are working on biodiversity research, I think that especially on biodiversity research, all of us can see how important it is to have this common effort. We don’t have the time for people to be okay, I want to save everything myself. It’s not going to work. We need collaboration. We need to help each other and share tests because this is the only way we can make the impact that we need in this sense. So to summarize would be don’t be afraid, people are not that bad. And worst case scenario, you’ll learn something from the critiques, start slow, but start and don’t be afraid to be scoped or anything. You still have the flexibility to have your passion projects stored for you, so to say.

Jo: Yeah, also like with the scooping, that’s actually the opposite. Can protect your work and your ideas by having your eyes assigned to any documentation you put online so that it’s sizable and people will acknowledge your contribution. And maybe one last word, because I also had it during my PhD. When it comes to, I think it was commonly referred to as, the imposter syndrome. When you work on a research project that has a potential huge impact. And many of us researchers start our careers with purpose in mind, or we want to contribute to something bigger. We want to save the world or find a treatment for disease or rescue an animal species from extinction. And many also just want to do research for research sake, to explore, because we’re curious. And that’s just as valid as a driver for being a researcher in the first place. But now when it comes to opening up to share our results, I also felt like this is so little who would potentially be able to benefit from me sharing this? And this is even good enough. Was there a point where you realized, well, yes, of course it’s good enough. And everybody’s contributing a little piece to the bigger puzzle. And I think you explained it beautifully, like through the exchange of putting our cards on the table, basically online, also in some cases closed research networks and digital infrastructures that are not open to the public because they might be sensitive. But then you have the opportunity to collect feedback and import information that will further inform your research, basically. I also already gave my answer to the

question. Would you agree with that?

Ludmilla: Yes, absolutely. I actually need to make a small note because I came across it a couple of weeks ago that this idea of imposter syndrome might even be a bit debatable in the sense of the origins of the term. I can share with you where I read it because I’m not into psychology that much but the origins of this term, they put a lot of weight on the person themselves when it might actually be also a result of the environment where they are. So I’ll give you an example. So I grew up despite my age. I did not have a functioning computer and Internet at home until I was almost 20. So this computational part of work came through me quite late if I would compare it to some of my colleagues. So when I arrived in that city, I was, oh my God, I’m so behind. What am I doing here? And I don’t know half of the things that these people know. And you can think of even less privileged people that they might end up in research positions that are waiting, they’re going over their heads. But it’s not like they are imposters. It’s just that they are trying something that is completely new and that they were not prepared for. And this might generate this feeling of inadequacy that it’s not their fault. So this is something that I need to acknowledge here because I learned from it recently and I think it makes sense. But coming back to whatever is the origin of this inadequacy, like I said, I think this sentence that you said, it’s like putting your heart on the table is the most important. Because as I said, not only you will most likely find people that are actually interested in it, whatever is the topic. Like you said, if it’s something that is totally relevant and it’s a totally urgent problem or it’s blue research, like completely out there; question that you have, it’s most likely that you will hear from someone that appreciates it and is interested in it rather than someone degrading or downplaying it. And also, as I said, do it. Go ahead and do it and get it wrong and someone will fix you. And then you’ll learn something from it because it’s better than being in that fear state of is it good enough? Is it relevant? Isn’t it? You have to talk to other people. You and yourself and your supervisors can only do so much. And as soon as you start opening up, you’ll see that you have the positive feedback, if not from your immediate circle, then it even shows the bigger necessity of opening it so you have even more input and eventually you get new ideas and so on. So it’s this idea of, okay, go out there if it’s great, if it’s bad, you have learned something from it.

Jo: And it will even pave your career like it did for you. That sounds interesting. It is not much, but I can make my research fit into this program and the call is not specific to my research. And then next, two years later, you have a paid position to further inform research, to support researchers doing better research and having better outcomes of the research altogether and eventually that has a positive impact on conservation biology.

Ludmilla: Yeah, exactly. This is the thing. At the discussions, this is very important because of this. Because I realized that it was a common need that people were working on themselves. But as soon as we started sharing, we had something bigger and more useful to apply, to improve, right?

Jo:Yeah. Thank you so much, Ludmilla, for joining us today and I’m really excited. Stay in touch. I look forward to hearing again from you having other conversations in the future about how to bring your lab notebooks to more people out there and also for you to facilitate the researcher Institute and the broader research network to do better data management properly and we can all learn from each of these examples altogether. Thank you so much.

Ludmilla: Thank you. That’s great

Part 2: Computational notebooks for more openness, reproducibility, and productivity in research

Jo: Ludmilla welcome back to this show, our podcast and Access 2 Perspectives, where we have conversations with experts in research, science management, entrepreneurs, and we’re very happy to have you here again. We’ve met before in this digital space and room where we talked about your work, where you’re basically helping researchers to curate data, and we talked about fair principles and conservation biology, which is your expertise. And we’ve also worked together. We’ve done all of the work, and I was just giving some feedback here and there. Wikipedia open science fellowship program.

Yeah. So now we’re here to celebrate as a result of your work, not only to design, should I say super simple or easy to use electronic notebook for computational and also paper that is the very same. Tell us more about the journey, how you’re feeling now?

Ludmilla: Yeah, sure. First of all, thanks for having me back, for being the mentor of this work, and also for helping spread it around. The idea of this paper, the idea behind my whole participation in the Franciscan System Fellowship was to, as the title of the paper says, was to create a simpler way for researchers to organize the computational part of their work. And this came from my own experiences during my Masters and my PhD, because I had, like many of my colleagues, I’m a biologist and ecologist, and then I got into writing code and using other people’s code. And at first this sounds quite chaotic for us. We just grab pieces of code, put on scripts, run, get the results, put the results on papers, on presentations, and the whole thing, over time can get a bit overwhelming and completely disorganized.

Jo:It sounds quite exciting, but it’s also an iterative process, right? You start from unfinished code, size it, optimize it further, adjust it to your research context. It’s not meant to be perfect, but it’s to be cleaned and the process will be functional. In a way, it’s part of the process. But also there’s a need for some structure to make it easier to manage.

Ludmilla: Yes, exactly. Like I said, it’s not straightforward. It’s not like we think of an analysis, run it, put the perfect graph together, and that’s it. We publish a paper now, we try many things. We explore routes that don’t look like they are going to, they’re not clear at first, and then we have to set it aside. So this whole thing happened, at least for me, it wasn’t the last ten years doing my Masters in my PhD, which is where there was this boom of computational ecology where I actually work, where it became more and more popular. And this is what I would see with me and my colleagues. We would have a bit of a hard time organizing, like really day to day work of, okay, where do I save my script? How can I make that? I don’t have six versions of a single script so that I can save different versions, one to seven, and then I have to read it through to know what’s happening. And at the same time, there are many tutorials available online, which is great because everybody very much has this idea of a community helping itself, so everyone would write a bit of an introduction to organizing code and how to write documents code and so on. But because of this. Despite the variety of tutorials. I would still come across the same problems as my colleagues. Especially those who are not so much in the computational part of stuff. Because I did my PhD at the University of Wurzburg. And I was a student of the zoology department. But also of the center for computational theoretical biology. And there is where it’s heavily focused on computational studies or computational techniques. And this is where I came in contact, really, with what it is to work day to day with code and all the practices around it, because you have software development running for years, and they have their own established practices in the market, right? So you have these huge teams and very secretive and important code that is running like there’s money running on those codes. So those techniques, how they say they passed down to academia, but not so much, because the academics are not computational sciences usually, right? Of course, they are the computational sciences. But we were taking some techniques from computational sciences, and this is where I saw this whole world of how you document code, how you work together with people on the same code, and how you share how you document it. And again, a variety of resources of tutorials and so on. And I would still see there was this very specific occasion where we used to have these unSeminary discussions where we would share common problems that we had. So it was a moment for all the students, all the PiS, to come together and talk about some questions that they had, some interest that they had in common. And one of them was how to organize a work. And I saw that there was a variety of strategies, and none of them was perfect, were perfect, and people were still like, yeah, at some point, I lose control, and I have to rush for a paper, and then things just get bundled up in a folder somewhere in my computer, and the paper is published, and then I get rid of it. Don’t get rid of it, but your paper is done. And that’s basically something. Yeah. And I mean, it’s like, okay, the paper is out. Whoever reads the paper will understand the general idea. If they have questions, they come to me. But I still, especially for a PhD. And the idea of the thesis, of writing a thesis where everything is connected, it’s like a three to four year work, body of work. So I still would miss this continuous ability to track things. So I started to develop my own system, and I presented it to my colleagues and everybody. Most people liked even this first version, which was a complete mess, and they gave me ideas about how to make it more efficient and so on. So I polished it a bit. And then when I read the announcement of the Franciscan Fellowship, I said, well, okay, this sounds very much in line with what I like, with what I’m doing, actually. And also during this whole process, there was this idea for me that I wanted to make my work as open as possible for it to be scrutinized, because at least as a PhD student, you’re like, okay, sometimes it’s like, what am I doing? Is it correct or not? So I made it. I tried my best to make it as open as possible, so wherever there was ever a mistake or anything, people could see it right away and check and so on. So I said, okay, it would be nice to have some time and some resources to dedicate to make it something that I could share with others, right? Because those are my practices, my script. I would just run them, put my workflow together. But it would be nice to have the time to test some ideas and check if there was anything available to improve it. So this is how I use this as my basic project to apply for the Francisan program. And then when I got in, we got all that mentoring in much, which opened my eyes for the world of open science even more and helped me prove the package, in a sense, to make it more, how do I say more focused on what it could do. Because we can have all these practices of documenting work, publishing it, documenting code, sharing code, and then you have different tools for it. But I think in the end, I didn’t want to have a comprehensive tutorial for all of this because, as I said, there is this big variety. I said, okay, let’s be very specific and focus on the day to day work of a scientist that has a lot of things to do and also needs to start tracking your work. Because besides the question of this being a good practice of properly documenting and sharing your work, it’s becoming increasingly important with funding agencies, and it’s become an important item in research and CV to see that they have shared their code and their data properly and documented well and have it been reusable. And as I said in the previous iteration of the podcast, it’s better to waste time, so to say, thinking of new ideas and coming up with new questions, then trying to reinvent the wheel that someone else already used. So as soon as we make it easier for people to share their code and others can find it relatively easy and reuse it, we put our brains in our time to better use.

Jo: Great. So if I’m going to take you back to where I thought I was originally coming from with conservation biology, and now what’s special about your personal career is that you merge with computational science. And so what is the benefit that computational research is bringing into conservation biology? What’s the leverage aspect and which then eventually led to you coming up with this toolkit for computational notebook? How do you envision this to be useful also for other disciplines or other research disciplines, really, to further inform our research computational analysis?

Ludmilla: Yes. Just to be very specific here, I’m not so much of a conservation of biologists per se. I was more into the theoretical part of the college with some consequences for conservation biologists, just so that people don’t think I’m working directly with conservation. But the work that I did, I studied animal extinctions, and this is why I use the models. We try to predict what would happen in ecosystems where extinctions are happening and so on. So there is, how do I say, a conservation component to the outputs of my work. But to your question, I would say that having this computational part being documented and open and shared is important because of the trust that it brings to the work, where people can actually check and evaluate how it is that you’re making claims. For example, Okay. These species are going to go extinct in the next 100 years or so. Or this species that brings about extinction. It is important to whoever it is. It’s either the public or other sciences or whoever the stakeholders are. That they can understand how it is at work and not just think. Okay. You put these numbers into some black hole of mathematical magic. And then you come with these predictions which are not grounded in reality. And this is something that it’s something that is recognized, especially in the field of computational ecology. There is this whole work by fork cream and collaborators where they push for this principle of traceability, where there’s this whole framework for, okay, justify your scientific question, inform it well. Track all the data that you used to base your questions, all the data used to base your hypothesis, how you build your experiments or anything, and how you verify your results. The idea is that it is understandable not only for scientists. As I said. We’re probably going to reuse our work. But for the public who has to understand. Okay. The biology of the question is. Okay. I have species going extinct. Or I have some ecosystem that is threatened. And what it means when I go in with a model. With something completely abstract. When I make experiments with this mathematical experiment and they bring out these numbers. How it is that I can trust that they relate to reality. So if you have this well documented, of course it requires some work. It’s not like it’s popular science, it’s different, but it allows specialized people with different degrees of knowledge, I would say, about the field. So you don’t have to be a computational scientist, you don’t have to be a scientist. I mean, you don’t have to be strictly an ecologist. You can still follow the reasoning and build some questions and then discuss, and have some ground for discussion. And of course there is always going to be some aspect that is very particular, some statistical model that is quite hard to grasp, but at least it’s documented. It’s not just some assumptions that you made and that you stretch the bits here or there to make it look significant or relevant or how they say or very drastic claim that brings attention to your work, you make your work.

Jo: It’s not rigid and reliable, basically.

Ludmilla: Yeah, exactly.

Jo: Can this also be applied to climate research, to model climate scenarios?

Ludmilla: Yeah, in theory, yes. I think the climate models, they’re much bigger in this sense. I mean that it’s not like you can take your personal computer and run that model and you’re going to get the same results. You probably need some more powerful machines, but the idea would be pretty much the same that you can document, okay, what are my assumptions? Where is the code that I ran? And then if someone wants to scrutinize it, they would be able to do it. And this is also something that I incorporated in this kit that I wrote, where it’s not necessarily that you have to put all the code inside there because as I said, sometimes the code is too heavy. Even my old code needs some high performance clusters to run. But you point to it and then you point exactly what are the outputs of that brand that you bring back in your research.

Jo: So that’s the level of fair, where fair data comes into play. Where it’s not only findable and accessible. But also interoperable and therefore they eventually reusable in a package form and basically in your own personal or professional notebook. Which is easy to handle even for non data scientists like I am. With a minimal understanding of coding languages and syntax. As we also describe. So what is the computational aspect of the notebook based on? I see that you use maximum syntax and RStudio, which even I understand, and again, I just have basic knowledge of HTML and then through some work in GitHub, just networking really, and documenting on GitHub, I’ve learned about Markdown, which is very similar, and that’s where it ends for me. But also I don’t have to design or work with code. But it doesn’t go much further than that, right?

:

Ludmilla: Actually, the notebook, I wrote, for two text editors. You would say one of them is our notebooks, or which uses the R Markdown syntax language. And this can be used when people are programming in R and Python, which are quite popular in biology and ecology. But also I use the plural notebooks, which are for Julia language. And the idea of using our notebooks and plural notebooks is that, yes, they have this. You can use the R markdown syntax, which is nice, that you can have normal descriptive text and codes embedded into it. So the idea is that you can describe the code in a block of text or give some introduction to the code that is not comment code in the script, and also have the blocks of code immediately followed by their outputs, be it plots or tables or summarizing values, but they are relatively easy to use. So both our notebook, which you can open in our studio and the Pluto notebooks, have this visual interface where you immediately see your file with the combination of descriptive text, the code and the output of code. You can see it live. So it’s not like you have to compile and then have another file being produced to see the output of your code. So both of them, they have these very nice interfaces where it’s relatively easy to see, okay, how is it that I put a block of text in this document? How is it that I put a block of code here? Where is my output coming especially for the beginners, where this idea of our markdown, of markdown sorry, language, where it might be a bit overwhelming, it might sound like another language where it’s like, okay, I have to learn R now, I have to learn Markdown as well, and I need to find something to convert it to HTML. So these two are notebooks and plural notebooks. They have this very visually appealing and easy to use interface where people can see right away, okay, I’m writing this code, if I press Enter and it runs, I see my output, I see if it makes sense or not. I see if it might take too long, it might not make sense to include it here. I see my figures immediately. And what is also nice is that all the trials that you might do, okay, should I run this analysis or this test? And then I see the output. But immediately after I can do a check of another idea that I had to check some detail of my question, for example, and you can still have it in the documents, you still have it in your R notebook file or your plural notebook file, but when you render it. So when you convert it to HTML, so to say, which is the visually appealing version, where you can read through and through, you can hide those things. So you can still have your site ideas or site project in that file, but not necessarily show them. You just keep that as a note to yourself that, okay, I tried this thing, it didn’t work, but I’m keeping it here just for future reference or something like this.

Jo: Cool. So that’s basically for transparency also to ourselves as researchers there’s also a scheme that one of my colleagues, Kalon developed where a researcher is basically complaining to another scientist like, oh, I can’t read that code anymore, or even the server was written in that notebook. And then, oh, have you tried calling the authors or have you tried getting in touch with the person? I was like, yeah, that was me a couple of years ago.

Ludmilla: Exactly. Yeah. This is something that actually came in the review process. Many of the reviewers actually said you can actually include in there that researches themselves would benefit from such a system because it’s not uncommon to waste quite some time to go back and realize, okay, what was I thinking when I was doing this? And this is something that I went through through my master’s and PhD. And at some point you have to find a solution.

Jo: What I also like about the paper, because it suggests a super simple folder structure and when you see it in front of it like, yeah, that’s how I would do it. But no, really, we all haven’t done it. All of you see it in front of you, but I think it’s because everybody’s just jumping into the research, you have a question and it gets more and more complex by the day. And then the documentation part takes a little bit of effort and time and it’s so vital to the process. So I cannot express too much or basically how important it is to have a thorough research plan which should be followed along. It doesn’t have to be fixed throughout. So of course there’s room for flexibility and adjustment depending on how the project goes. And you can also totally change the plan on the process, but have a plan in mind and work along it and then document the heck out of it.

Ludmilla: Yeah, the idea about this folder structure, like I said, there are many times where I created this folder structure, like manually making my folders. But the thing about the kit is that once you run the function, it establishes that it creates those folders for you inside that structure. So this is like one line of code that you have to run and it’s named and everything. And also, as I said, as I say in the paper, like I said, the documentation part, it takes a lot of time. And this is why we try to go for the simpler starter kit because we don’t want to give researchers even more work. I mean, it’s necessary work, but we all know how crazy busy researchers usually are, especially early career ones. And the idea for this case is that by having this notebook, either the army version or the Pluto version, it can store all your thought processes. And we give some references in the paper as to some other people who suggest how to keep it up, and how to structure the file itself. But the idea is that you have that single document where you store all your ideas, your code, your trials and tribulations with your work. And then, let’s say you can transfer from there some bits that are going to the main text of the publication. Either be of text, let’s say, for example, descriptions of analysis, or figures and tables, but the rest stays in there and the file can be given as supplementary information for the reader. You don’t need to provide single figures and table several files. You give that whole thing, the figures will be named. You can give captions to all of them. And then it reduces the amount of, like we were saying, like the amount of files that you’re handling, where you’re like, okay, figures, supplementary figure one, version A, version B, or something like this. You keep everything in there and you render it at the end of your work. In both cases, we explain more in detail how you can also inform what is the computational environment that you use. So all about the operating system and the packages and software that you might have used for that analysis so that is also preserved. And then when people receive your work, they can also reuse it and establish the same conditions that you had to run your analysis. And this idea of making things simpler and as I said, the minimal amount of work possible was very strong from the beginning because I think we even might have had some discussions that this was something that reviewers of the fellowship program said from the beginning, that it was like, okay, there are quite a few tutorials already. Let’s see what this one brings, why yet another one is important. And I think this is where we went with it to make it simpler, not only to write code and document code, but to integrate it into the publication process. Because this is where things have to be polished and understandable, right?

Jo: Yeah, exactly. Many notebooks that I’ve seen, as I said, they’re super complex because they try to fit in many possible scenarios and complexities for medical research, bioscience, big data analytics, whatnot. And then there’s not really a product for most researchers in their early career like this one, but maybe can we say a few words about scalability? So you said that the photo structure is kept simple, the functionality is kept as simple as possible. And now how scalable is it? To what extent can it be complexified, if that’s even worse? Or with somebody who needs more complexity than what’s presented here? Would they need to go to another system or can it be extended in some way?

Ludmilla: Well, as I said, for example, I’m thinking of this because if we think of what the notebook is supposed to contain is some descriptive text for what you’re doing, the code that you run for it, and the output, riight? So I think things can get complex depending on the data that you’re using, the amount of data where you’re getting it from both the amount and the sources and also the size of the code and the language that you’re using. So this. As I said. Was focused on R. Python and Julia and I know at least for R there are some packages that allow you to run C code and I think as I say. You could integrate some lines of code in your notebook. Okay. Now we run this very big script or this very big model. But it’s not going to be totally included in the documents. The whole code is not going to be literally copied and pasted there. But there is a pointer to it and this is where the part where the scalability might come into place is that as I said, it’s not like a user that receives your notebook will be able to run that and run your model and get back the same results. There might be some issue with accessibility to the code or to a big machine to run it, but at least the pointer is there. Yeah. So this would be one way of working around it, I would say. And as for the data, we always have the issue of confidential data, right, that cannot be shared and again it would be pointed out in the paper how that data was manipulated. Of course the reuser would probably not be able to rerun the notebook and get the same results because they don’t have the data, they don’t have access to. But the idea is at least that the reasoning behind all the wrangling that goes around the analyzes, the transformation that happens, that it can be followed. So I see this idea as this issue of scalability would be more a matter of, okay, the reuser might not be able to rerun it, reproduce it literally, but they will understand what you did. And this barrier of access I would say would be more initial of confidentiality, which I don’t think we can have a look around and also the size of machines which has to be set up I would say would have to be discussed with. But even there are some cases where for example, I’m pretty sure Pluto notebooks have it and I’m pretty sure R mark studios have it, where you can run a notebook in a special environment. So special environment is not the right word, but I’m missing it. But you can have access to some computational power online. So I’m specifically thinking of binder which will let me get you the right term here. I think I forgot about it. Yeah, it’s an executable sorry, environment where you can depend on your code, you can create this environment and it runs and it’s remotely so if your code is on a GitHub repository, you plop it in there with the name to a notebook file and then it creates a docker image. So computational reproduction sort of depends on your environment, of what is necessary to run your notebook and then you’re able to do it remotely so online. So I’m pretty sure this would work for cases where the user cannot do it on their own machine.

Jo: Yeah. That’s great and I think as we said before. It’s a prime example for fair data management like using skit basically sets you up for fairness. Findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable and even where it has its limits, it provides plugs for other systems to be connected with that.

Ludmilla: So to say yeah. Which again comes back to that idea of making things simpler and it’s very good at being very simple and then once people are comfortable here they’ll probably find a way of just plugging in the more complex bits. I think the cases where this would happen would be not as numerous as the cases where this simple installment will be very useful, you know what I mean? I think there are many people there. The number of people that will benefit from having this simple kit that gets them started in doing reproducible computational work is much higher than the people that are working with these very huge projects where they are already used to those practices anyway. This is something that we mentioned in the kits that we don’t talk about building big ecological models or big software practices because the people doing this. They are already familiar with this practices anyway so even though we want everybody to use this but the idea here is really for the ones who are just starting so that they can feel comfortable and then they start making it their own and as I explained. I think the kits gives a very general base where making it more complex is not that complicated it doesn’t break anything. It doesn’t break in structure.

Jo: Cool and will this also be useful as an electronic lab notebook to embrace for researchers who do not yet do any work with codes and algorithms but might in the future just to set themselves up for any possibilities of expanding their data processing? Would it be useful for an ecologist or molecular biology? And we never had large enough samples to do any sort of statistics really because it was more about qualitative analysis but I still appreciate the photo structure and people might still work with code but not have to quote themselves and then what I’m trying to also had is that developing a code in academia ten used to be not so what’s? The acknowledgements were scarce in the past but now it’s becoming more and more evidence is what I’m trying to foster in my trainings to acknowledge code development and adding code developers also to the list of contributors or authors of the paper of course it’s always a matter of debate to what extent like the code help to come up with whatever conclusion which then carries the message of the paper basically will it also enable to facilitate collaboration between biologists and data scientists for a common goal on a project.

Ludmilla: Yeah, for sure. Because as I said, these notebooks contain descriptive text and code, but it doesn’t need to have a code part for it. So you can think of these notebooks as your Word file or library Office file, where you would write your electronic notebook, as I said, if you have it locally. And another reason why we used our markdown in total notebooks is because they are very easy to follow when you’re under version control, right? So if you’re using GitHub to maintain your work, it’s very easy to follow, to see where you change. So you can mark the lines that change very easily. And this is where this aspect of sharing your work with others becomes important and also making it a form of electronic notebook because let’s say you want to log in your work every day, you would have every day to change that is happening. And then if you need to go back to justify for some reason to someone when a decision was made or anything, you would have that in version control. We don’t go into detail into the version control aspect of it, but we provide references, as I said. Yeah, so sharing it with Data Scientists would be pretty common. The use of such notebooks is pretty common in Data Sciences, so I think I would be happy to do it. And another thing that you said about acknowledging code is also something that I mean, we don’t mention it directly in our kit, in our paper, but it’s something that as you have this notebook and you have, for example, let’s say there’s a very specific piece of code that you wrote, let’s just say, okay, this is my baby child that I created. You can put that thing separately in the note, for example, publish, get a DOI for it and mention it in the notebook. And then when people reuse it, they will see that that has been deposited somewhere and then you can get credit for it. So it’s not like it’s hindering anything.It’s not like you would say, I developed this very nice piece of code and now people are just coming in and using it without technology. Now you can still make it a module, a separate module, so to say, of your work that you get people to acknowledge and we also talk a bit about in the paper.

Jo: Yeah. So the MacDon language allows for an R syntax sorry. It lasts for version control. And you can also track who contributed what. Does it allow for more than one person to work in the notebook?

Ludmilla: Yeah, I mean, if you have a GitHub repository, for example, and I think there might be even services, I’m not sure on this one, but there might be services from our studios where you can contribute to the file at the same time. I mean, I’m not sure, but there might be but in any case with the classical form of having a GitHub repository where you do your changes, you share it and you send to other people, as long as they have R studio, either locally or remotely, they can access and edit it and document their chains. So they are marked down. It’s pretty much marked down. It’s only that I would say some easy, how do they say, shortcuts that you can use in R studio. So for people who are familiar with Markdown, it’s pretty much the same thing.

Jo: Yeah. Cool, great. Is there like a dream use case or like a wish that you have like where you would like to see this come through? Obviously it’s proving useful as it’s been documented. So I don’t have any doubt like how can we yeah, what’s necessary to get it to as many people who might find it useful and then also implement or how’s it been so far? I think we talked about this in the last episode but since we spoke it’s been half a year or so. How’s adoption going? And what can anybody out there listen to support the project and to support bringing this to you rather?